hroughout the years of the Cold War, Italy was one of those geographical areas that, had the war become hotter, would have turned into a battleground. The Italian peninsula was a sort of fence that separated the Western from the Eastern World. As a matter of fact, Italy shared its borders with, respectively, Central Europe and Communist Yugoslavia. There were few doubts about the fact that had the Soviet Union decided to start a territorial invasion, Italy would have been one of the first theatres of war.

hroughout the years of the Cold War, Italy was one of those geographical areas that, had the war become hotter, would have turned into a battleground. The Italian peninsula was a sort of fence that separated the Western from the Eastern World. As a matter of fact, Italy shared its borders with, respectively, Central Europe and Communist Yugoslavia. There were few doubts about the fact that had the Soviet Union decided to start a territorial invasion, Italy would have been one of the first theatres of war.

Italian Politics

Nonetheless, since the end of the Second World War, Italian politics had always been dominated by Democrazia Cristiana (DC). The DC was a Catholic-inspired centrist party that had never denied its loyalty to the United States. Still, such a political dominion had always been challenged by the Italian Communist Party (PCI), which was the strongest Communist Party in Europe. The PCI reached its peak of consensus during the General Elections of 1976 when 34,37% of the Italian electorate gave it their votes. The second-largest left-wing party in Italy was the Socialist Party (PSI). Although it pursued Socialism, the PSI had already broken off its relationships with Moscow in 1957 as a response to the Soviet Union’s repression of the Hungarian Uprising. In 1963, the DC and the PSI gave birth to the first center-leftist government in the history of the Italian Republic.

A Path to Communists’ Participation in the Italian Government

At the beginning of the 1970s, Aldo Moro (DC) and Enrico Berlinguer (PCI) started to negotiate Communist participation in the Italian government. According to Moro, the Communists were not a revolutionary party anymore, and their secretary Berlinguer was slowly moving away from Soviet Union obedience. Additionally, throughout the 1970s Italy was devastated by terrorist attacks and the killing of politicians, judges, and journalists. Some form of political unity was thus needed.

On the other hand, according to Berlinguer, the only way for the Communists to take the power was through the Italian democratic institutions. The PCI needed to be recognized as a fully democratic party to prevent the United States from reacting as they had done against Salvador Allende in Chile in 1973.

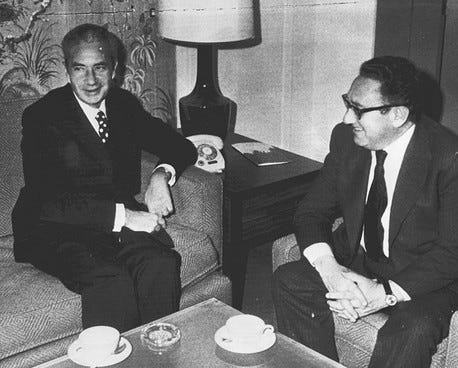

Kissinger Threatened Moro

Nonetheless, many leaders on the Western side of the Cold War did not share Moro’s thoughts. Instead, they believed that such a political strategy would have brought Italy into the Soviet Union. Henry Kissinger, United States Secretary of State from 1973 to 1977, was one of the strictest opponents of Moro’s strategy.

On September 25, 1974, Moro arrived in Washington as Italian Minister of Foreign Affairs. While there, he also met Kissinger. During the meeting, Kissinger showed Moro all his resentment. Moro’s wife, Eleonora, reported that Kissinger told the Italian: “Either you cease your political line or you will pay dearly for it.” In 2020, some of Kissinger’s memorandum written to President Nixon were published and one of them dealt with Moro being a danger for the Western World. After the meeting, Moro canceled all his appointments and went back to Italy. According to his collaborators, Moro felt badly and, as a matter of fact, he disappeared from Italian political life for a few months.

On March 16, 1978, Moro was kidnapped and, more than fifty days later, killed by the Red Brigades, a far-left armed organization. Although this is another story, what is interesting to notice is that, among others, one of the reasons why the Red Brigades killed Moro was because they did not want the PCI to join the DC in the Italian government. Nonetheless, the very same day of Moro’s kidnapping, the PCI voted in favour of a new DC government.

History, Politics & Economics – A place for uncomfortable truths.

michelecaimmi98[at]hotmail.com