ncient civilisations’ passion for colours is more than understandable, without it, life would be colourless, grey and an endless abyss. It was the Tyrian purple, the Egyptian blues, their precious golden shades and Persian turquoise that brought excitement into antiquity. But even though their take on colours, mirrors our modern vision, and our awareness of their importance, there is a fundamental gap.

ncient civilisations’ passion for colours is more than understandable, without it, life would be colourless, grey and an endless abyss. It was the Tyrian purple, the Egyptian blues, their precious golden shades and Persian turquoise that brought excitement into antiquity. But even though their take on colours, mirrors our modern vision, and our awareness of their importance, there is a fundamental gap.

Their perception of colours and how to apply the colour system itself is light years apart from ours, to the extent that it is extremely difficult to understand ancient texts and books that speak about colours, without having enough background information on how they apprehended colours and the world in which the colours exist.

The world of colour is endless, considering that every civilisation, culture and time period has its own perception of colour, it becomes an endless jungle!

The best way of coming to terms with this endless jungle of colours and ancient civilisations’ mysterious colour vocabulary is to get a hold of the key to solving the mystery. The key is to better understand ancient peoples’ reasoning through their history and languages.

Egyptian Blues

The Egyptian civilization was the first to both name and use the colour blue in their paintings and dye (for clothes).

“As the only exception” they used and named the colour blue very early on in history.

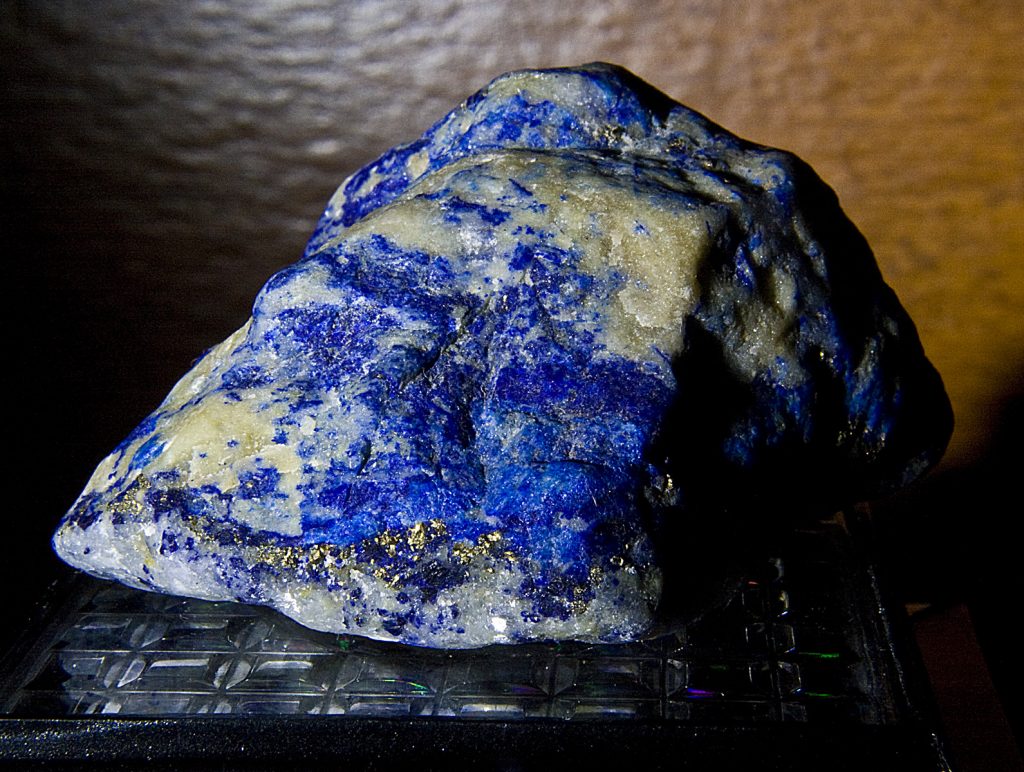

The Egyptians started to import Lapis lazuli from Afghanistan as early as 6.000 years ago. Lapis lazuli is a semi-precious gemstone, also known as “true blue”.

They started by trying to make paint out of the powder of the gem, but without satisfactory results, they proceeded to make their own “Egyptian blue”, for their paintings and dye, through a chemical process and used the Lapis lazuli, which was “expensive and precious as gold” for jewellery, instead.

The Egyptian hieroglyph for colour can also be translated as “being”, “character”, “disposition”, “nature”, or “external appearance”.

This clearly illustrates the significance of colour as being an essential and integral part of the ancient Egyptian worldview.

In 2006, scientists discovered that “Egyptian blue” glows under fluorescent lights, indicating that the pigment emits infrared radiation;

Egyptian blue – was created from copper, silica and calcium: CaCuSi4O10.

Green– was created from malachite (a natural copper ore).

Black – from carbon compounds (soot, ground charcoal) or animal bone.

Red – red ochre, hematite.

Yellow – yellow ochre.

With Egyptian civilization as the only exception, linguists have discovered, after careful examination of ancient texts, that almost all other languages followed a fairly standard timeline of when names for distinct colours were introduced; black and white, being the most ancient of the colours, followed by red.

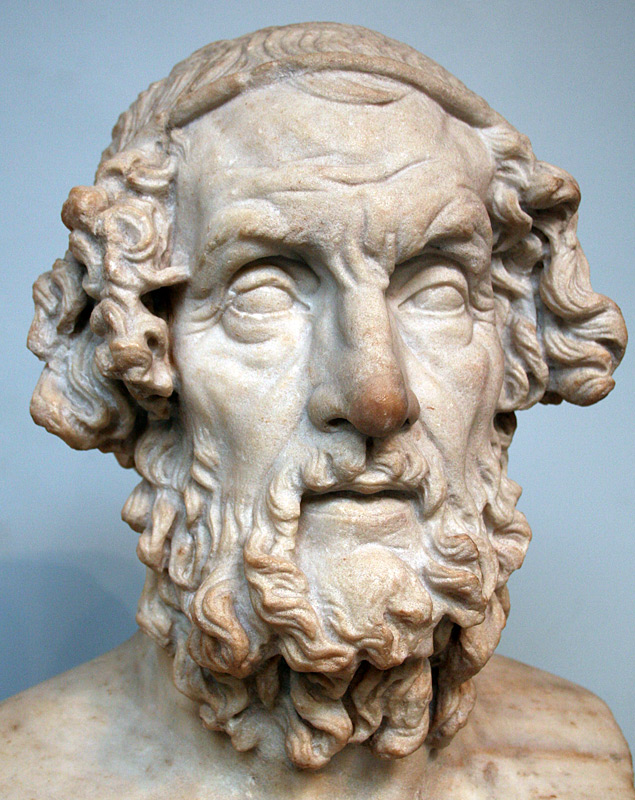

Homer, the classic Greek writer, and father of western literature has long confused and puzzled modern linguists with his unusual way of describing colours. Classicists have pored over Homer’s works: Iliad and Odyssey, desperately searching for any mention of the colour blue, but in vain, there is no such mention anywhere in the texts.

Even more surprising is the way Homer refers to colours in general and compares them to things in nature in a way that makes no sense. His reference to colours is deployed in an extremely odd way that is incomprehensible to us…

The Greek Colour Enigma

Although Greece is surrounded by infinite shades of blue, iconic blue roofs found across its islands, rich sapphire seas, and bright blue skies, the conspicuous absence of a distinct word for the colour blue in Ancient Greek seems unexplainable.

In spite of their close relations with their Egyptian neighbours, they seemed to have missed out on that point.

Surprisingly the word “blue” is simply missing from nearly all other ancient languages as well.

There was no distinct word for the colour in Chinese, Hebrew, Sanskrit or Greek, rather, the colour we call blue was usually grouped with other colours, such as green.

Homer compared the sea, not to the sky or other blue-coloured objects, but to “wine”, which is shocking but quite interesting. Throughout Homer’s poetry, the sea is repeatedly referred to as “wine-dark”.

Moreover, Homer refers to honey as “green” and sheep as “violet” in his works, leading 19th-century academics to believe that either the Ancient Greeks were altogether colourblind or they hadn’t yet developed the necessary capabilities to see colours as we do.

To be able to better understand Homer’s descriptions and the century-long colour dilemma we first have to be able to understand the underlying reasoning for the use of this peculiar choice of words.

In the Ancient Greek worldview, everything existing on the face of the earth was classified into four elements: air, earth, fire and water, representing hot-cold, and dry-wet. These four elements existed individually, separated from each other or in combination with each other, often mixed together.

Mixed into innumerable inorganic and organic compounds, giving the basis for substances and beings that could be classified as: minerals, plants, animals and man. The order was hierarchical with minerals having only one element (earth) and man having all four.

The ancient Greeks’ perception of colour was very different from ours. To them colour was not an attribute you gave to an object, colour wasn’t seen as a dead surface, it formed part of the substance itself.

A colour was a spirited thing, a part of the element or compound to which it belonged. The Stoic Greek philosopher, Zeno, summons it up in his statement:

“Colours constitute the first determinant of (the form of) matter”

Simply put, the world consisted of four matters: Water, Air, Earth and Fire. And these four matters were of four colours: Black, White, Yellow and Red. When the matters were mixed with each other the colours were also mixed, producing many more shades and degrees of other colours.

Cases in point are; Chlōros, translated as “green” used to describe; tears, limb, blood, fecundity, freshness, honey, vitality and nature.

Porphureos, translated as “purple”, but also used to describe “heaving movement”, something softly moving up and down, thus commonly used for describing the surging sea.

Argos, translated as “bright, gleaming white” but also used to express; nimble, agile or swift-moving activity (as of dogs or horses running, likely because the strobe light refracted through running legs was similar to bright flashing light).

But rather than describing a specific colour, ancient Greeks frequently referred to the shade or tint of the hue instead, considering colours in a shade from dark to light.

In Ancient Greek, the word “kyaenos” was often used for colours on the darker end of the spectrum, including what we now know as violet, black, dark blue, brown or dark green.

Our modern word “cyan”, a greenish blue, comes from this word. Also used for darker colours was “melan” (dark), our modern word melancholic comes from here.

“Glaucos” or “leukron” was frequently used in reference to light colours including; yellow, grey, light green or light blue.

Further, they commonly used “ōchron” – pale, and “lampron” – shiny.

Language and Reality

To the Ancient Greeks, blue was a shade on the dark scale without having its own individual name.

In English, colour can function in the opposite way, linguistically. Consider the colour pink: pink is on the red scale, so if we had no word for pink, it could easily be considered as light red, and we would refer to it as such.

Yet as we have a distinct name for the colour pink, we perceive it as a different colour than red.

Another hypothetical example: If a dog was somehow taught to speak elementary English, he would find the language remarkably poor in its names for scents.

Words develop from the need to express names for things we notice or care to talk about, and the limited colour vocabulary in many ancient languages is most likely due to this.

The Romans’ Obsession with “Purple”

In Ancient Rome, purple was the colour of choice and preference, it represented royalty and wealth, and was a status symbol.

And while purple is flashy and elegant, it was more important to the Romans that purple was expensive, because purple dye came from snails.

The colour originally came from Tyrus (modern-day Lebanon) and was called Tyrian purple, to obtain the colour marine snails were collected by the thousands. They were then boiled for days, in giant lead vasts, producing a terrible odour.

The snails are not purple to begin with, the craftsmen were harvesting chemical precursors from the snails, that through heat and light were transformed into valuable dye. In Rome purple was worth more than gold!

Romans of late antiquity, with their complex political hierarchies and sophisticated court iconography, distinguished dozens of terms for what to us simply looks purple.

Words develop when there is a need for them! Thus, Latin became enriched with words for purple.

The Dinkas and Their Browns

The nomadic Dinka tribe in southern Sudan is traditionally thought to have dozens and dozens of terms for the colours beige, yellow and brown.

The vocabulary has adapted to their living conditions, they live in a desert surrounded by their beloved cows and livestock, and they possess over 400 different words to nominate their cows.

In fact, they name most of their colours after the shades and patterns of the cows they value so highly in their lives, bovine chromatography abounds all around them.

Even nowadays different cultures can determine colours differently and develop a distinct colour vocabulary, and the Dinkas are a good example.

Another country with a different colour code is Russia, in the Russian language, there are two separate terms for the colour we simply call blue.

Scientific Colours

By passing light through a prism a rainbow of colours will appear: red, orange, yellow, green, blue, indigo and violet, which makes up the visible spectrum.

The visible spectrum is the narrow portion within the electromagnetic spectrum that can be seen by the human eye, there are further other waves of energy that we cannot see.

In the modern world, there is no shortage of reminders that there are seven colours in the rainbow. We know that colours blend into each other in an infinite array of shades and hues. But we are still persuaded to look for just seven colours.

Colours that developed through trade

Turquoise

The etymology of the colour itself can be traced back to the 17th century and the source was the mined stone.

It appears that there was a multitude of trade routes that brought the turquoise gemstones from Persia through the Middle East and to Europe, but the paths all crossed through Turkey (Which is the origin of the name, Turkey being “Turquíe” in French, and “Turquoise” meaning Turkish stone).

The stone got its name from here, but many people still doubt whether the stone gave its name to the colour or vice versa.

In other words, which came first: the chicken or the egg?

In light of the information, the right answer is that the stone, or mineral came first, and then came the need to name its colour. Though the credit should be given to Turkey, which happened to be in the trade route of the precious stone and consequently giving both the gem and the colour their names.

Another example of a name of a colour that came to be out of necessity is Orange…

Orange

Europeans wouldn’t have known what to make of the colour, until the 16th century. Up til then, orange was simply a variant of yellow and red. Orange was not officially recognised as a colour by English speakers until orange trees were imported from Asia.

It was the introduction of the colourful fruit that called both for a name for the fruit and a nomination for its colour.

In English, the word orange stems from the old French and Anglo Saxons “orenge”, that in turn originates from Latin “pomulus de orenge”.

The image of the unique wine-dark sea is powerful, it remains in my thoughts, whether it is burgundy in colour or purplish red, dark red, maroon or purple violet makes no difference.

The deep image prevails over all other descriptions, and combined with the bronze sky, an old shade of blue with a slight touch of bronze or gold, maybe from the sun, completes the beautiful image.

It is easier now to understand Homer’s description of the “wine-dark sea of immortality” as we have insight into how Ancient Greek colour vocabulary functioned.

We also have to keep in mind that Homer was a writer, and his works are poetic, not scientific.

The rest is just a matter of culture. In the end, we are all part of history.

It may well be that future generations will look back at our colour preferences in shock. Those new civilisations may well wonder why we never used or talked about a colour, which to us would simply look like a variant in shade, but would constitute a notable, easily recognisable and important colour. The sea of colours is endless!

A History, Travel, Culture and Language writer, eager to learn more and explore the world.