November 4th 1890, the then 22-year-old Tsaravich Nikolai II Alexandrovich Romanov would depart from the Russian port of Gatchina to embark on a year-long educational journey east. Among the countries he would visit were Egypt, India, Sri Lanka, China, and lastly Japan. Although the purpose of the future Tsar’s journey was diplomatic, aimed to prepare him for the intricacies of policy and foreign culture proximate to Russia, his last journey to Japan would prove to be a brutal awakening to the realities of an increasingly modernized world. So much so that the journey may have caused enough trauma and disdain to justify a war that would eventually prove significant in the collapse of his dynasty.

November 4th 1890, the then 22-year-old Tsaravich Nikolai II Alexandrovich Romanov would depart from the Russian port of Gatchina to embark on a year-long educational journey east. Among the countries he would visit were Egypt, India, Sri Lanka, China, and lastly Japan. Although the purpose of the future Tsar’s journey was diplomatic, aimed to prepare him for the intricacies of policy and foreign culture proximate to Russia, his last journey to Japan would prove to be a brutal awakening to the realities of an increasingly modernized world. So much so that the journey may have caused enough trauma and disdain to justify a war that would eventually prove significant in the collapse of his dynasty.

A Sheltered Prince

Nicholas II was born during an increasingly turbulent time for European monarchies. Russia in particular had been experiencing increased pressure to reform even as serfdom was abolished and political movements like anarchism and socialism gained influence within the Russian underground. This increase in political unrest is a central theme correctly foreseen in Fydor Dostovesky’s 1872 novel Demons. With Nicholas’s grandfather Alexander II and his uncle Grand Duke Sergei Alexandrovich of Russia having been successfully assassinated, Nicholas’s upbringing was subsequently largley sheltered from the public. Once the prince came of age, Nicholas’s father Alexander III thought it would be appropriate for him to engage in a journey to prepare him for stately affairs. He would go on a tour of predominantly Eastern nations, and would conclude his journey at Vladivostok, where he would take part in the inaugural ceremonies for the Trans Siberian Railway.

The Eastern Journey

Nicholas and his delegation first went by train from Saint Petersburg to Vienna where they proceeded to Trieste, Italy. There they boarded the Pamiat Azova, a sturdy Russian cruiser that would carry the delegation on their seaward journeys. They proceeded to Greece where they were hosted by his uncle George I of Greece, whose son also called George would continue with Nicholas on the journey. From there Nicholas II and his entourage went to Egypt, India, Sri Lanka, Thailand, China and finally Japan. In all those journeys Nicholas was largely met with positive public reception, he was given plentiful gifts and respect from the nations and kingdooms he visited. He visited iconic cultural sites such as the Pyramids of Giza and the Taj Mahal and during his visit of Japan, the Tsaravich was noted to have respected Japanese culture and crafts, even as far as receiving a traditional dragon tattoo on his right hand. But this did not prevent the catastrophic end to his journey to the Empire of the Sun.

Nicolas II and his delegation had spent Christian holy week in Japan. While there they had visited Kagoshima, Nagasaki, Kobe and Kyoto. On May 11th, a week short of the Tsaravich’s 23rd birthday, he and his delegation journeyed to Otsu, a resort just outside of Kyoto, while there Nicholas and George toured the resort, took a boat ride on Lake Biwa and dined with the governor of the region. Once they finished lunch, Nicholas’s entourage rode in a procession of rickshaws to catch their train back to Kyoto. Nicholas was near the front of the delegation, riding in an open air rickshaw, with the governor and police officials behind, all in a group of about fifty rickshaws. The day was going to plan and the Tsaravich would be in Kyoto shortly it seemed. But a constable standing guard by the street had a different idea and planned to send the Tsaravich somewhere else that day.

Tsuda Sanzō was a policeman born into a samurai family who had previously fought in the Satsuma Rebellion, a revolt helmed by influential samurai Saigō Takamori, against the Japanese imperial dynasty. Sanzo had fought for the victorious imperial side, but the event had unsettled him as he had revered Takamori. His deep seated patriotism for Japan and suspicion of the Russian Empire would put in motion a self-fulfilling prophecy of sorts between the two nations.

The Attempt

On that day as Nicholas’s rickshaws turned into the narrow Shimo-Kogarasaki Street of Kyomachi Ward, Tsuda Sanzo drew his sword, lunged forward and swung his blade at the Tsaravich. He had aimed for his neck but the Tsaravich managed to duck, and the blade struck his hat which muffled the slash. The exact account of the event is uncertain as it happened so suddenly, but most accounts say that Prince George either parried the second blow or helped the other rickshaw drivers neutralize Sanzo. Nicholas was rushed to a nearby store where the wound was dressed, and subsequently taken back on the train to Kyoto. He had sustained a 9 cm long scar on the back of his head, that would stay with him for the rest of his life. Once Emperor Meiji of Japan recieved word of the incident he boarded a train as quickly as he could from Tokyo to Kyoto. The Emperor visited the Tsaravich as he was recovering on his Russian ship and expressed his dismay. The Tsaravich was said to be in as happy of spirits as you could be recovering from the incident, but this did not stop him from cutting short his Japanese journey.

Following the events, the governor of the region of the attack (Shiga Prefecture) and the Japanese Foreign Minister resigned, it was forbidden to name a child Tsuda or Sanzo in the attacker’s home district. Sanzo was given life in prison as Japan did not have a death penalty and he died in captivity in 1891, rumoured to have starved himself. The rickshaw drivers that apprehended Sanzo were applauded and honored, given a hefty monetary reward of 2500 yen, though future hostilities between Japan and Russia would render their reverence sour, and the rickshaw drivers would lose their pensions.

The War for the East

As the years progressed, Nicholas’s wound never fully healed. He continued to suffer headaches that would be attributed to the incident, equally tensions between the two nations would not relent.

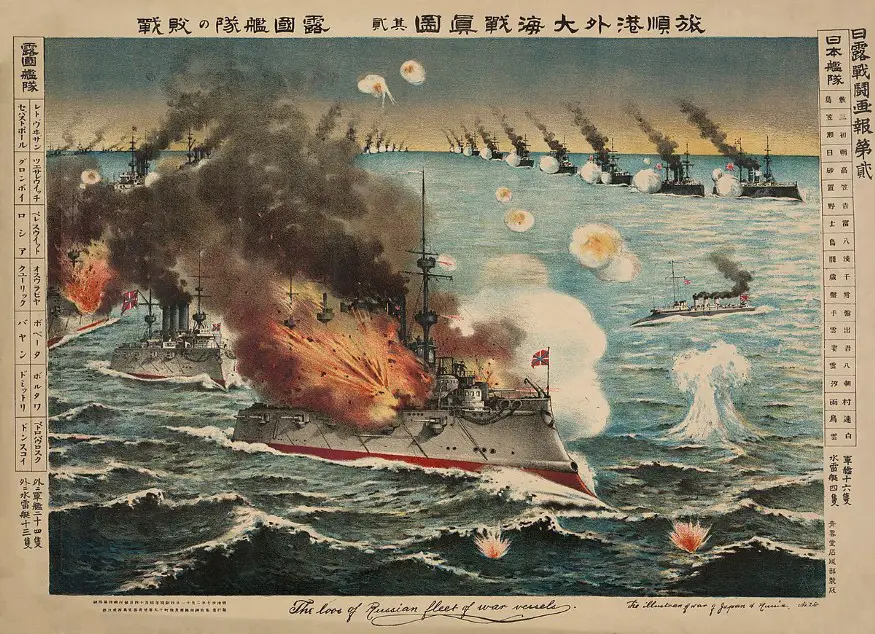

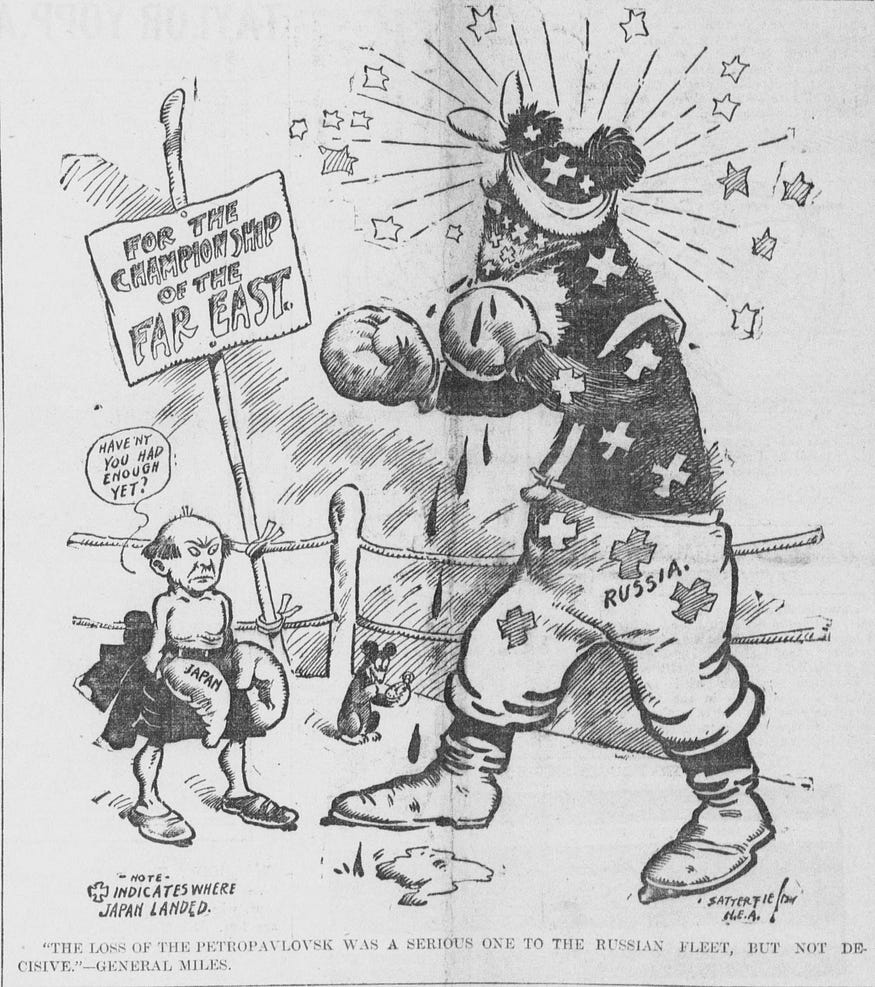

As the 19th century concluded, Japan had rapidly developed into a burgeoning middle power on the world stage, and their aspirations for Eastern supremacy had become clear as they defeated the declining Qing Dynasty of China in the first Sino-Japanese War. This put Japan in an increasingly conflictual position with the Russian Empire’s perceived authority over the Sea of Japan. Vladivostok, the major city which is situated on the Sea of Japan was ceded from China to Russia in 1859 as a result of China’s loss in the Second Opium War. The Russians named the city Vladivostok which translates to Lord of the East. Russian aspirations were apparent and they wanted to secure an all season port into the East. Both countries feared the other would hinder their own geostrategic interests in the region, and soon the inevitible happened and Japan declared war and attacked the Russian operated naval base of Port Arthur in Manchuria on February 9th 1904. What resulted was a year and a half long war throughout Manchuria and Korea resulting in large casualties from both sides.

Initially the war was met with tolerable reception from the Russian population. They rallied against the Japanese attack on Port Arthur and this war indicated renewed Russian efforts to bolster dominance. Nicholas was convinced that the Japanese were no match for the grand European Empire. However, as the war progressed, it became increasingly difficult to sustain and the war was far away from most of Russia, requiring significant resources from the Empire. Russia was always on the back foot.

Nicholas entrusted his faith in divine favor, the same divine favor that he would thank for sparing him from assassination. He believed that God favored him and the Russian Empire, furthermore he saw the Japanese Empire as unsophisticated and effeminate, refering to them as little monkeys in letters.

In response to the attack on Port Arthur, after much deliberation Nicholas ordered Russia’s Baltic Fleet to mobilize to Japan. This was against the advice of many of his chief advisors including his Grand Admiral and proved to be a mistake. The decision would come to be emblematic of the Russian Empires disarray as the paranoid Baltic Fleet would open fire upon British fishing boats on the North Sea, mistaking them for Japanese torpedo boats. The blunder, known as the Dogger Bank incident, resulted in the deaths and damage to both the British and Russian fleets involved, and heightened tensions between England and Russia, beginning the development of a narrative of incompetence for the Russian Empire.

The Baltic Fleet would later be decisively defeated seven months later in it’s first significant conflict in the Battle of Tsushima, effectively ending the Russo-Japanese War. This would be the first time in the modern era that an Eastern power would have defeated a European power. The war marked significant developments in military technology such as rapid firing artilary and foreshadowed the carnage of World War 1.

The End of an Empire

Although perhaps a coincidence, one cannot help but look back at Nicholas II’s relationship with Japan as a catalyst for his downfall. Nicholas’s mindset regarding Japan was undoubtably marred by a racially based arrogance toward the once imperialized Japanese, but could his uncharacteristicly headstrong attitude toward the Russo-Japanese War be a manifestation of vengence for the attempt on his life? The extent to which the attempt on his life affected his attitude is still debated, but the events that followed have bled into modern history.

Japan established themselves as the most well composed and efficient powers in Asia, largely free of many of the chains of imperialism that hindered other Asian powers, this efficiencyand autonomy would remain for years to come and grow with the already present nationalism that would later burgeon into facism and resulting in terror for neighbouring countries in decades to come.

The Russian Empire and Nicholas were also set on a cursed trajectory, however their’s would end much earlier than the Japanese Empire’s. Following Russia’s humiliation and the growing protests among the Russian population during and after the war, the Russian constitution was revised in 1906, but this resulted in a galvinization of competing political factions and diminished the power of the Tsardom. It was during World War I that the Tsardom would collapse from further societal discontent and Tsar Nikolai II and his regime would be overthrown by the incoming Communist regime. And the rest is living history.

Christian Nelson is a writer published on various publications on Medium. Having lived in many different countries and experienced many different cultures, Christian hopes to use history as a tool in unearthing similarities from the past and the present while shedding light on forgotten events of the past.