he 300 Spartans “legend” is quite famous among history fanatics as it presents a small army going against all odds. This story, heavily publicized in 2006 when the movie 300 came out, tells the tale of the epic battle of Thermopylae but forgetting some 0’s along the way as well as changing some facts to make the story more captivating. This battle did take place, but there weren’t 300 soldiers, but more like 4000 of them, still making it an impressive act for such a small army to go against massive hordes of enemies. However, things are complicated and to get a better understanding we need to first have a look at the Greek culture.

he 300 Spartans “legend” is quite famous among history fanatics as it presents a small army going against all odds. This story, heavily publicized in 2006 when the movie 300 came out, tells the tale of the epic battle of Thermopylae but forgetting some 0’s along the way as well as changing some facts to make the story more captivating. This battle did take place, but there weren’t 300 soldiers, but more like 4000 of them, still making it an impressive act for such a small army to go against massive hordes of enemies. However, things are complicated and to get a better understanding we need to first have a look at the Greek culture.

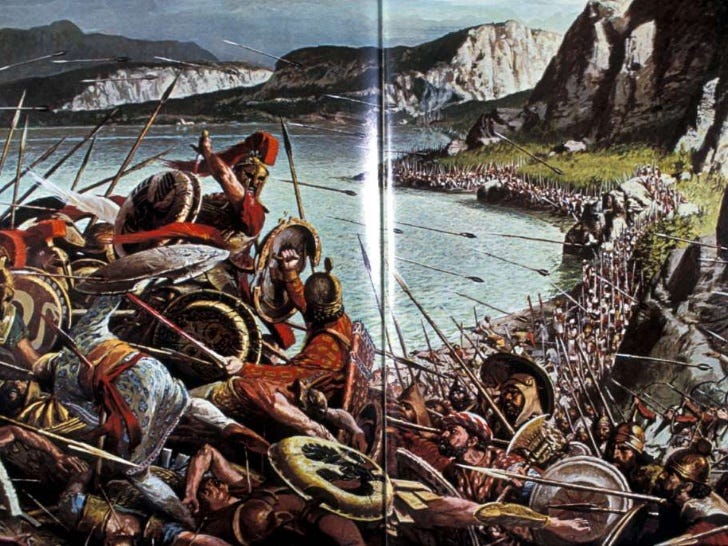

Around 2,500 years ago, there were wars between an empire with an area of eight million square kilometers and a Greece divided into several city-states. It resembled the biblical struggle between David and Goliath. An empire with numerical superiority could destroy Greek civilization, along with its ideas and culture. But history teaches us that quality is often better than quantity, and the Battle of Thermopylae proves this.

A group of Greeks under the command of King Leonidas and his Spartans would face the largest army ever assembled in antiquity. The Battle of Thermopylae was not, however, a decisive battle in the Greco-Persian wars, but it revealed the ideal of the people to sacrifice themselves in the name of freedom even 2200 years before the great modern revolutions. Who were these Greeks who resisted and fought so bravely?

“This is Sparta”

Ever since he was born, in 540 BC, like any Spartan, the infant would have a life full of trials. For the Spartans, life was a constant struggle for survival. From the very day of his birth, his mother bathed his fragile body in a large vessel filled with wine to see if the child was strong enough to withstand a life full of challenges, cruelty, and struggles. If the baby survived this test, he was subjected to a new test. His mother brought him before Gerousia, a council of thirty members, most of whom were over sixty years old. They inspected the baby’s body to see if it was fragile or deformed. If he did not meet the eugenic criteria, the baby would have been thrown into the abyss on Mount Taygetos. But this was a lucky baby.

That baby would be called Leonidas and would live in a religious society that focused on military training. Leonidas was himself the son of the king of Sparta, Anaxandridas II, who had two wives. The first wife was barren, so the ephors allowed the king to take a second wife without driving away the first. His second wife was a descendant of Chilon of Sparta (one of the seven Sages of Greece). She bore him a son, Cleomenes. However, his first wife eventually gave him three sons: Dorieus and the twins, Leonidas and Cleombrotus.

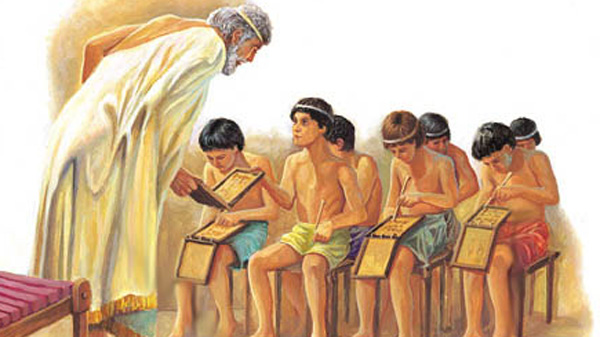

Agoge system

As he was not considered the heir to the throne, at the age of seven, Leonidas began his hard military training in the Agoge system to become a killing machine. The training was designed to discipline, train, and develop the physical tenacity of Spartan boys. Leonidas, like many other Spartan boys, lived in common barracks and was fed strictly with the necessary amounts of food, neither to starve nor to satiety. The boys learned to fight, steal secrets, to get food, but at the same time, they were taught to write, read, sing, and dance. They were severely punished if they did not speak laconic (in short).

The boys were frequently whipped at an early age, in order to get used to the pain and to be hardened for battle. They were not allowed to talk much, to complain, or to criticize. Any Spartan had to complete three stages during training: paides (seven to seventeen years old), paidiskoi (seventeen to nineteen years old), and hebontes (twenty to twenty-nine years old). The boys lived in agelai groups under the coordination of an old man and were encouraged to have increased loyalty to Syssitia (common mass). From the age of twelve, the boys received a phoinikis, a red cloak to hide their wounds. They built their own shelters and beds on which they slept, without tools, but empty-handed. They were used to enduring hunger because it strengthened their resistance.

Like many other Spartan boys, Leonidas had a mentor (an elderly unmarried man) who was his second father and a role model for development. Pederasty was often practiced in those days. It was essential for any adolescent to form a special relationship with an old aristocrat in order to form a free citizen.

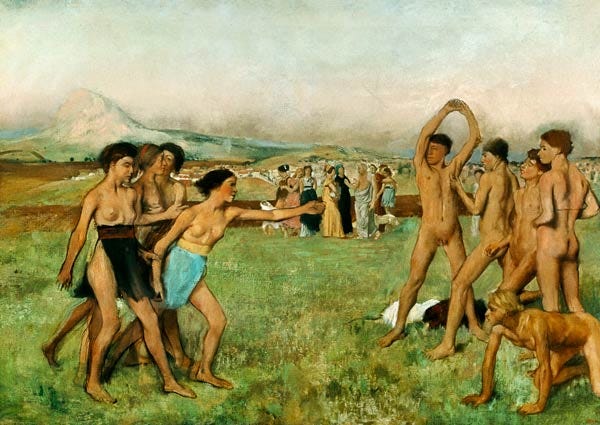

Spartan children and adolescents were subjected to various trials and hard training. During winter, they were sent to forests and mountains to hunt and fight wild animals in order to sharpen their senses, sleeping in the open air, dressed scantily and without shoes, or sent to steal from the markets without being caught. Leonidas probably also faced the test of survival outside the city, through the wild where he hunted for food and killed wolves and other wild animals, using his fighting skills to survive.

At the age of eighteen, Leonidas became a paidiskoi, a student who could serve in the Spartan army. He was allowed access to the Crypteia-secret police, which was trained to spy on the helo-producing population. From 465 BC, young Spartans were sent to kill vulnerable helots. The helots were followed in the hierarchy by periodians, who were not Spartan citizens, but were free men. Even women were trained to fight and have a good physique so they would give birth to healthy babies. Men were taught to fight in the phalanx, to protect themselves and their comrades with the hoplon (shield).

At the age of twenty, Leonidas, as a Spartan citizen, became a member of the Syssitia-club of common meals, each consisting of fifteen members who had to learn how to relate to each other and to whom they contributed financially. He lived in a barracks and continued his training to become a hippeis.

It was not until the age of thirty that Leonidas, like the other Spartans, was able to participate in political life, either in elections or to run for public office. The Spartans hated the Athenian democratic model. Like any Spartan, he was placed in active reserve until the age of sixty, becoming homosexual (equal), and living a disciplined lifestyle. As for marriage, like any Spartan man, Leonidas had to kidnap his future wife. If he managed to kidnap her, he would take her home, shave her to baldness, and then put her in a ragged cloak and leave her on the floor in a dark room.

He didn’t have to be drunk or helpless. He would have dinner with her and then take her to bed to give birth to a baby. He had to visit his wife in secret during the wedding. Many men shared their wives with guests, and many unmarried young men could sleep with other men’s wives to carry their babies. But Spartan women enjoyed high status, power, and respect and were literate. They did not marry until they were twenty years old. They had to train to give birth to healthy children. They wore comfortable (peplos) dresses cut up and to the side.

Leonidas married Gorgo in 490 BC, and in 489 BC, became one of the two kings of Sparta after Cleomenes died without a male successor to the throne, and Dorieus was killed in Sicily. Sparta was an oligarchic city-state ruled by two hereditary kings of the Agiad and Eurypontid families, both claiming descent from Hercules. The kings had religious, legal, and military responsibilities.

Persians on the hunt for land and water

481 BC: horsemen from the east appeared as messengers from the great king-god Xerxes of Persia. Messengers roamed the Greek lands to demand “land” and “water” — a form of obedience to the Persian Empire. But Athens and Sparta refused and decided that they must form alliances and defend themselves. The Corinthian Congress was held in the autumn, during which an alliance of city-states was formed to send troops to the defensive points. The news of Xerxes’ forces crossing the Hellespont shocked the entire Greek world. Themistocles suggested a new strategy: blocking the narrow passage of the Thermopylae coast (Fire Gates named after the hot springs).

The Greek hoplites could thus stop the Persian advance. At the same time, Athenian and other city-state ships were sent to blockade the Artemisium Strait. The double strategy was adopted by congress. Meanwhile, Greek spies reported that the Persian army was advancing slowly through Thrace and Macedonia.

The Persians preferred to fight from a distance with bowed arrows. A single Persian army of 10,000 archers could launch 100,000 arrows in a single minute. Cavalry was often used in open battles to harass the enemy with “hit and run” attacks, shooting arrows and throwing spears from the flanks.

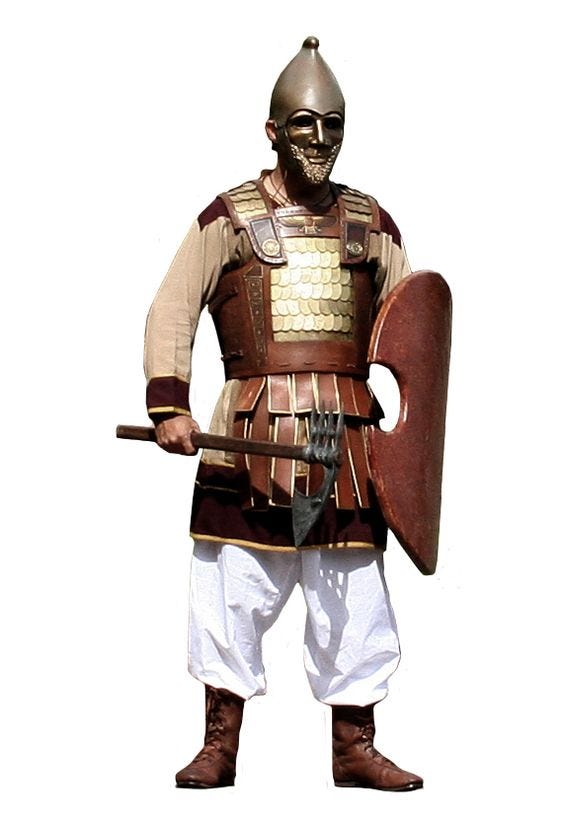

The immortals were equipped with wicker shields, short spears, large swords and daggers, and bows. They wore armor from links under their clothes and tiaras. The Immortal Regiment was followed by a caravan of camels and mules carrying supplies, along with their concubines and servants.

The Spartan profession

On the other hand, the Spartans were equipped like any Greek hoplite: chiton (tunic) or exomis, himation (cloak), bronze foot coverings, armor with bronze pectorals, and Corinthian helmets. The Spartans wore long hair and beards. They had no other obligation than to fight and train all their lives, given that the production was provided by helots.

They were equipped with wooden shields covered with a layer of bronze (it was not until 420 BC that the letter Λ-lambda from Laconia was painted) which were passed down from generation to generation. Grouped, they could fight in the formation called “phalanx”. Each Spartan was defended by his comrade next to him. They fought with the “dory” — the long spear or with light spears which they threw at the enemies. They were also armed with a xiphos, a secondary weapon, a 30–45 cm sword, or a kopis, a curved iron sword. They even knew how to box.

According to estimates, the army gathered by Leonidas who would oppose the forces of the largest empire at the time consisted of: 1000 Lacedaeomians / Periods, 300 Spartan hoplites, 500 Mantinas, 500 Tegens, 1000 Arcadians, 400 Corinthians, 200 Filians, and 80 Mycenaeans. The number of Peloponnesian forces thus rose to 4,000. Secondary forces from other city-states were to join Leonidas: 700 Thespians, 1,000 Malians, 400 Thebans, 1,000 Phoenicians, and 1,000 Locrians. All of them were ready to fight to the last, without compromising or thinking of retreating.

The sixty-year-old Spartan king-general thus led an army of 7,000 soldiers, of whom only 4,000 were Peloponnesians, and only 300 of them had been trained for a lifetime to fight 300,000 Persians.

Gates of Fire

The two passages were defended against the Persian invasion. The land passage, Thermopylae, was defended by 7,000 Greeks while Artemisium was defended by 271 ships. Thermopylae was the place where the numerical superiority of the Persians did not matter due to the difficult relief. A phalanx of hoplites could stop the advance, without the risk of being surrounded by enemy cavalry. The disadvantage was that the phalanx could not carry out an assault on the Persian light infantry.

The weak point of the Greeks was the passage of goats through the mountains, parallel to the Thermopylae passage from where they could be surrounded. The good news was that Xerxes still didn’t know why it was passing. Along the passage were various bumps and rocks that narrowed the path, as well as a small Phocian wall.

At the dawn of a hot day of August 20 / September 8, 480 BC, Xerxes sent a spy to observe the Greeks. The spy noted and told him that the Greeks were doing gymnastics exercises and that many Spartans were combing their long hair. When Xerxes received the news, he suspected that the Spartans were preparing to die as a man. Demaratus, a former king of Sparta who ruled with Cleomenes and who deserted in 490 BC, joining the Persians, warned the king that he would face the bravest men in Greece.

Xerxes was desperate. He had been hoping for four days that the Greeks would withdraw. On the fifth day after the Persians came to Greek territory, it was thought that the Greek resistance was of great indifference and impudence. Therefore he sent an envoy with soldiers to take the civilians as prisoners. But the Phocian wall erected by Greeks fighting shoulder to shoulder, shield to shield, in a narrow space would compromise the Persian assault.

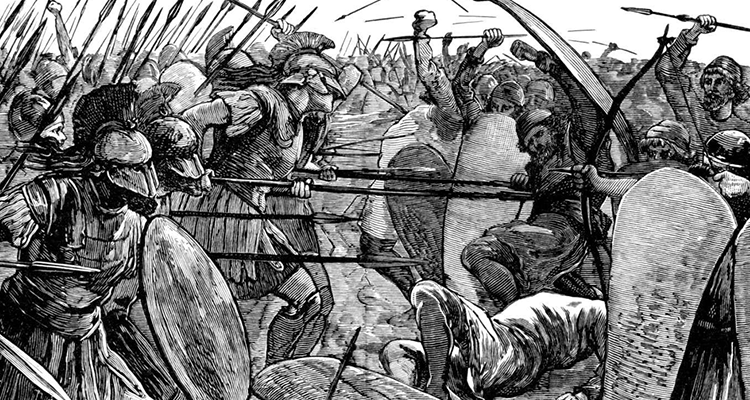

The Median horsemen hastened their advance and attacked the Greeks, but were overwhelmed by the long spears of the hoplites, resulting in terrible losses. They were repulsed by the broad shields of the Greeks and stabbed by long spears. The archers shot arrows at the Spartans, but without success, because their shields seemed impenetrable.

It was clear that despite their numerical superiority, Xerxes had fewer fighters than the Spartans. But the brawl continued throughout the day. The Medes finally withdrew from the battle. In their place came a division of “Immortal” Persians led by Hydarnes. Each dead “immortal” was quickly replaced by another.

Unfortunately for them, the Immortals used shorter spears than the Greeks. The Spartans defeated them with their superior fighting techniques and proved skillful. A large number of “immortals” were killed. Few Spartans fell in battle. Behind the phalanx, light spear throwers and archers confused the Persian attackers. The Spartans simulated a retreat and then dealt them a final blow and destroyed the legendary “immortals”, proving that they are mortal.

During these attacks, it is said that the king-god Xerxes, who was watching the battle, jumped three times from his throne, feeling a slight human thrill on his spine, seeing how the two attacks were repulsed. Towards evening, the Persian troops retreated to their camp.

No king or general dared to contradict the “God” king, no matter how good a strategist he was. The commandments of the king-god were sacred and had to be obeyed. It did not matter that the Persian army, even with its numerical superiority, was technically and qualitatively inferior to the Greek forces. It did not matter that the relief at the battlefield was very disadvantageous to his forces and that he risked losing his entire army there. He did not want to learn from the mistake of his father or King Darius, who had lost the Battle of Marathon ten years ago, also because he did not take into account the small imperfections, underestimating the Athenian army. But he was confused because even now he had failed to defeat an inferior Greek force.

The Spartan’s weakness

The next day, the Persians thought about how to find a weak point of the Greeks. The Greeks were organized into detachments after their hometowns and fought hard while the Phocians were stationed on the mountain to guard a pass. They continued to attack only to taste the Greek iron again, and so they retreated to their camps again. The Spartans mercilessly massacred the attackers. Xerxes was confused. He couldn’t believe he was thinking of withdrawing or suspending the campaign. The Phocian wall (though not smaller than one that even a hen would jump) accompanied by the Greek phalanx was impenetrable.

But a miracle happened: in his tent, the guards brought a certain local (probably a merchant or shepherd) named Efialtes from Trachis, the son of Eurydemus from Malis, who had a secret to share for a rich reward. He revealed to the king the secret pass that would bring him victory. King Xerxes, being glad, ordered them to show them to his soldiers under the command of Hydarnes, and to lead them personally at night to the mountain pass to Thermopylae. The path led from the east of the Persian camp along the ridge of Mount Anopaea behind the rocks that guarded the pass. At one point, the path forked, one road leading to Phocis and the other to Malis Bay at Alpenus, the first town in Locria.

At daybreak, Persian forces surrounded the Phocians defending the pass. The people of Phocis heard them walking because of the rustling of the oak leaves. The Persians rushed upon them with a rain of arrows. The Phocians rushed to the ridge of the mountain. The Persians thought it was not worth delaying because of them and quickly descended the mountain. Then Efialtes fled to Thessaly. The Greeks at Thermopylae were surrounded.

Leonidas received news from spies that the Persians were marching on the surrounding hills. So he decided to hold a council of war. Some generals and officers supported the retreat, others demanded to remain fighting. Even though some of the troops left for home, some of them decided to stay under Leonidas until the last moment. Leonidas himself ordered an air force to be formed to allow the other troops to retreat, preferring to fight honorably to the death and instead save 3,000 soldiers. He remembered the prophecy of the oracle that a great Spartan king would perish to save Sparta from barbarians. Some 700 Thespians and 400 Thebans remained with him.

At sunrise, after making libations, Xerxes ordered the army to advance and descend the mountain. The Greeks led by Leonidas remained to guard the passage. The Persians approached, and Leonidas’ Greeks grouped at the lighter part of the passage. If in the previous days they guarded the passage inside the wall, now they jumped over the wall to fight in the narrowest space. The final fight took place at the gorge. Piles of Persian soldiers were killed by the phalanx, while the chiefs whipped their squadrons to advance. Many Persians were thrown into the sea by the Spartans. A large number of Persians were trampled by their comrades. An indescribable crowd formed. The Spartans bravely resisted until their spears broke and they began to fight with swords, then with fists.

Leonidas fell in battle bravely. His comrades fought with the Persians for his body. The fight was horrible and bloody with many casualties. Xerxes even lost two brothers and grandchildren. 20,000 Persians were killed in the three days of fighting. Eventually, the Persians moved back, still enveloping them, and the archers fired a rain of arrows that killed the last surviving Greeks who were still fighting empty-handed. But the Lacedaemonian body behaved nobly, behaving as in a play. Even though the Persian arrows blocked sunlight, they said they fought in the shadows.

Revenge

The Greeks had lost a battle, not the war. A year later, 80,000 Spartans led by the nephew of the fallen king, Pausanias, were to defeat the 120,000 Persians at Plataea. Unlike the Athenians, the Spartans left nothing material behind. But their glorious heroism at Thermopylae and their lifestyle remained in people’s memory. The Battle of Thermopylae was a defeat for the Spartans, but in the long run, it was a victory for those fighting for freedom.

If you love the story of The Legend of the 300 Spartans, epic battles, and hot, intense military

campaigns. Maybe express your favorites and personality with items. Military Coins can be

customized through personalization, you can even add imagination and creativity to the design

of favorite military symbols and scenes, and favorite military stories or events can be customized

on both sides of the coin. Not only do they make great military souvenirs, but they can also be

given to like-minded friends.

Avid Writer with invaluable knowledge of Humanity!

Upcoming historian with over 30 million views online.

“You make your own life.”