traight through Europe, there is a rift that divides the Germanic from the Latin part. Even though it has shifted over time its existence can be traced down to one isolated event created by one single man, a man that permanently separated Europe; Armenius. Born from Germanic nobility, but adopted, raised and educated in Rome, Armenius spoke Latin better than anyone in Rome, and his knowledge of Roman warfare was impressive. He succeeded in winning the trust and respect of many high officials in the Empire. He was admired by the Romans and perceived as a useful liaison when it came to the struggle to romanise the lawless northern provinces known as Germania.

traight through Europe, there is a rift that divides the Germanic from the Latin part. Even though it has shifted over time its existence can be traced down to one isolated event created by one single man, a man that permanently separated Europe; Armenius. Born from Germanic nobility, but adopted, raised and educated in Rome, Armenius spoke Latin better than anyone in Rome, and his knowledge of Roman warfare was impressive. He succeeded in winning the trust and respect of many high officials in the Empire. He was admired by the Romans and perceived as a useful liaison when it came to the struggle to romanise the lawless northern provinces known as Germania.

But in spite of having received everything he had from Rome he betrayed it in a slaughter so horrifying, it would shake the civilised world to its core, halt the mighty Rome’s further advances in Germania, and forever create a rift between his birthplace and the empire that had raised him. The world that Armenius created then is still with us today; his actions changed the course of history!

A “Child Hostage” for the Roman Empire

For two thousand years, Europe has been suffering the consequences of one faithful event, and the actions of one single man: the Cherusci tribe’s nobleman Armenius. As the eldest son of the Cherusci chieftain Segimer, Armenius or “Hermann” in German, was born in northwestern Germany close to modern-day Osnabrück. To secure peace with Rome, Segimer is thought to have abandoned both Armenius and his younger brother “Flavus”, as a tribute to Rome as so-called “child hostages”.

The Romans controlled the tribes near the borders of west Germany. They would tax them and in an attempt to educate them and slowly incorporate them into the Roman culture and values, they would take the son of the tribe’s chieftains to Rome and raise them in a Roman family, and give them a Roman education known as a child hostage. They were later returned to their tribes or freed to stay in Rome, as they chose.

This was how Armenius ended up in Rome, received Roman citizenship, learned Latin and was given a military education and was even named an “eques”, or knight. As part of the Roman legions, Armenius was sent to serve as an auxiliary commander under Publius Quinctilius Varus in Germany.

Just as Varus took over the responsibilities of Germany, eight of the legions stationed in the country were suddenly sent to the Balkans, where it was felt they were more needed, suppressing what was known as “the Great Illyrian Revolt”, about half of all legions in the Roman world were sent there. This left Varus with just three legions left in Germania, the 17th, 18th and 19th legions.

The Complot

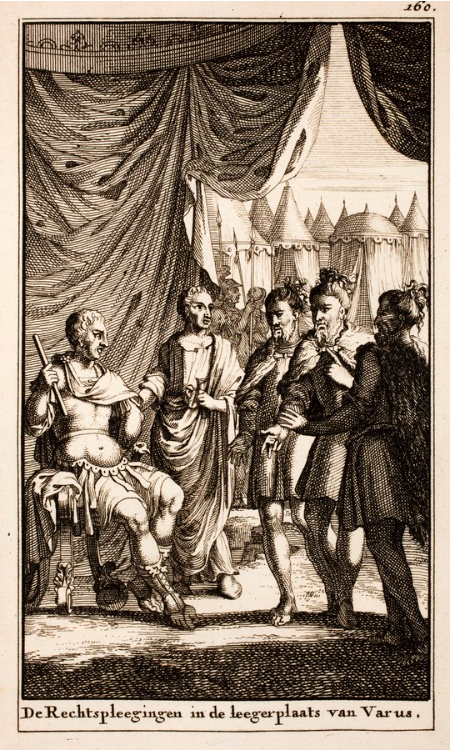

Arminius was busy in Germania, he was Varus’ top adviser on german affairs whilst trying to earn Varus’ trust while he was secretly uniting the germanic tribes against the Romans. During summer Varus’ legions were at the quarters on the upper Weser River and meted out Roman justice and law, while German tribesmen came to trade at the huge Roman Camp. For Arminius, however, it meant a chance to reunite with his family, and an opportunity to work on his plot.

Soon Arminius and Segimer sat together at Varus’ table, assuring him all was well. Arminius and Segimer’s goodwill was but a face, meant to fool Varus until the time was ripe to turn against him and the Romans.

Arminius knew the Roman legions would not go down easily. The huge Roman camp dwarfed the local village, and its fortifications made the legionnaires look nearly invincible. The Romans had better armour, weapons and discipline than the german warriors, thus to succeed they had to be united.

The Roman legionnaires were in the middle of their march back to the winter base, when Arminius came to Varus with news of an emergency that required his immediate attention. There was a rebellion amongst the tribes. Varus, in a moment of confusion, decided to reroute all three of his legions to get to the rebellious zone, as soon as possible. That route took him through an area the Romans were not familiar with. A place known as the Teutoburg forest, with a dense forest on one side and a bog on the other.

Varus had been warned by one of the Cherusci, a man named Segestes. He told Varus about Arminius’ dangerous plan before they sat out and advised him to arrest Arminius. However, Varus chose not to believe him, he trusted and liked his charismatic commander and thought such a thing was not possible and ignored Segestes’ advice.

Arminius knew from his training in Rome that the Roman legions were not equipped to fight in wooded terrain. A Roman legion was designed to fight as a unit in open spaces, where they could manoeuvre and fight as a cohesive unit, a war machine. It was standard roman tactics not to fight in a forest, but it was not their intention they had been tricked and forced into it.

Once in the forest, the Germans were waiting ready with their trap. The Roman army wasn’t walking in formation as they were not expecting combat, and were interspersed with camp followers, women and children, who would usually walk behind the soldiers. Varus didn’t send any reconnaissance ahead, thus they had no idea what they were walking into. The path was narrow and muddled, making it impossible for the Romans to organise any resistance, they were caught in a bottleneck. The Germans were outnumbered, but had the element of surprise and the knowledge of the terrain to their advantage and were able to cut down the long Roman line, stretched out along the trail piece by piece, little by little.

The battle lasted three days, the Germans had the high grounds and a wall they had built prior to the battle, to their advantage during most of the battle. A few Roman units were able to escape, but most of them were slaughtered and cut down in an unforgiving bloodbath, the worst in Roman history. On the third day, P.Q. Varus killed himself by falling on his sword, in an honourable Roman death. It was then the morale amongst the troops collapsed. The survivors, those who were not killed in battle were sacrificed in Germanic pagan ceremonies or enslaved.

Armenius’ lighter-armed, quick and nimble germanic warriors had beaten the mighty Roman army, and his gambling tricks had succeeded. In the mud of the torrential downpour, lost for all time, lay the Roman legions a total of at least 20.000 dead, an equivalent of ten per cent of the entire Roman military. The end result was the total annihilation of three Roman legions, chopped into pieces, they were never reconstituted again as long as the Roman Empire existed. The entirety of Rome’s military presence in Germany was abolished.

The Aftermath

The news hit Rome hard; they hadn’t suffered a defeat of this magnitude in centuries. Augustus himself was haunted by the loss of his legions for the rest of his life. He would walk around his palace hitting his head against the wall and shouting “Publius Quinctilius Varus, give me back my legions!”.

But the legions were gone and so was Varus. Just a few years after Augustus’ death, the new Emperor Tiberius sent his nephew Germanicus back to find the eagle stands and to seek revenge, he managed to secure several major victories but most importantly he recovered two of the three lost eagle stands the defeated legions had left behind. The third one was restored 30 years later and with it Rome’s honour as well.

The battle changed Europe and split it in two; one Germanic and one Latin part, a rift that lasted over 2.000 years and is still with us today. Armenius continued his killing spree by defeating Marcobaduus, king of Marcomanni and he became the most powerful leader in Germania. He even aspired to become their king, but many tribal factions resented his authority. Betrayed by his relatives, Arminius was murdered in 19 A.D. by his people.

Had Rome not been defeated, a very different Europe would have emerged. Maybe the “Thirty Years War” and the two world wars never would have taken place, and a more United Europe would exist today. In the end, Arminius belonged to two worlds, both the Germanic and the Latin, he had the potential and the knowledge few people had, yet he created a rift between his birth country and the empire that raised him.

Arminius chose Germania, was unfaithful to Rome and paid the ultimate price. Just as he betrayed Rome he was eventually betrayed himself, by the very people he sat out to free.

A History, Travel, Culture and Language writer, eager to learn more and explore the world.