March 26, 1964, the Czechoslovak government signed the death warrant of the entire city of Most. No one died as a consequence of this, though: it was the city itself — with its houses, shops, streets, theatres, monuments, parks, and schools—that was wiped off the face of the earth.

March 26, 1964, the Czechoslovak government signed the death warrant of the entire city of Most. No one died as a consequence of this, though: it was the city itself — with its houses, shops, streets, theatres, monuments, parks, and schools—that was wiped off the face of the earth.

In the early 1960s, a rich supply of lignite (a type of hard coal) was discovered in northwest Czechoslovakia, and the local authorities were very eager to launch mining operations there. There was just a minor disturbance — barely an inconvenience, really: the coal deposit was located directly underneath the center of a town.

The solution the government came up with was a very straightforward one: the entire city was to be razed to the ground and, to house the people who would become homeless as a result of it, a new town would be created elsewhere.

The destruction of the old town began in 1965, and it took almost twenty years to be completed: today, bulldozing down an 11th-century town to make space for a coal mine would be seen as a crime against humankind, but in the eyes of the Czechoslovak authorities – that’s just progress, baby!

A cemetery built in 1853 was torn down in the late 1960s. The town brewery, founded in 1470, was bulldozed in 1972. The local theatre, designed by Alexander Graf and dating back to the 1910s, turned to dust in 1981. This video documents some of the demolition process.

Centuries-old monuments were flattened, and the medieval city center, with its historical treasures, was obliterated. Some 55,000 people were moved into low-cost, standardized apartment blocks built specifically for that purpose a few miles away.

Out with the old, in with the new

The people of Most did not speak out against the demolition of the old town and their forced relocation: on the contrary, many of them were looking forward to it. The media fanned the flames, painting Most as a crumbling, dilapidated old place, unsuitable for modern people to live in.

The drab prefabricated concrete buildings of the new town — that look cheap and dreary to the modern eye — were seen as state-of-the-art and comfortable in the 1960s. The grey tower blocks had running water, central heating, modern kitchens, and large bathrooms, and that was a welcome change from the damp, drafty old houses the people of old Most used to live in. And old they definitely were: some buildings dated back to the middle ages, some were architectural wonders from the 19th century.

Even the Communist government, though — notoriously not a fan of religion and its symbols— recognized that the 16th-century Church of the Assumption of the Virgin Mary was worthy of being preserved. The people of Most revolted against the demolition of the one-of-a-kind church, and the late Gothic building was simply too historically and artistically noteworthy to be bulldozed down along with the rest of the city.

The government had to back down and start to think about a solution: they needed to find a way to save the structure and still be able to expand the coal mine.

After considering and rejecting other alternatives, like leaving the building where it was, perched on a coal pillar, or disassembling it and putting it back together in another place (it has been done with temples and even entire monasteries), it was decided to move it instead: a new location just over a half a mile away was selected, and the whole church was scheduled to be transported there — on wheels.

A committee was set up by the Ministry of Culture to supervise the project. Emmanuel Gendel, a well-known Soviet construction engineer who later became the USSR’s leading specialist in moving buildings (yes, that’s a thing) steered the works.

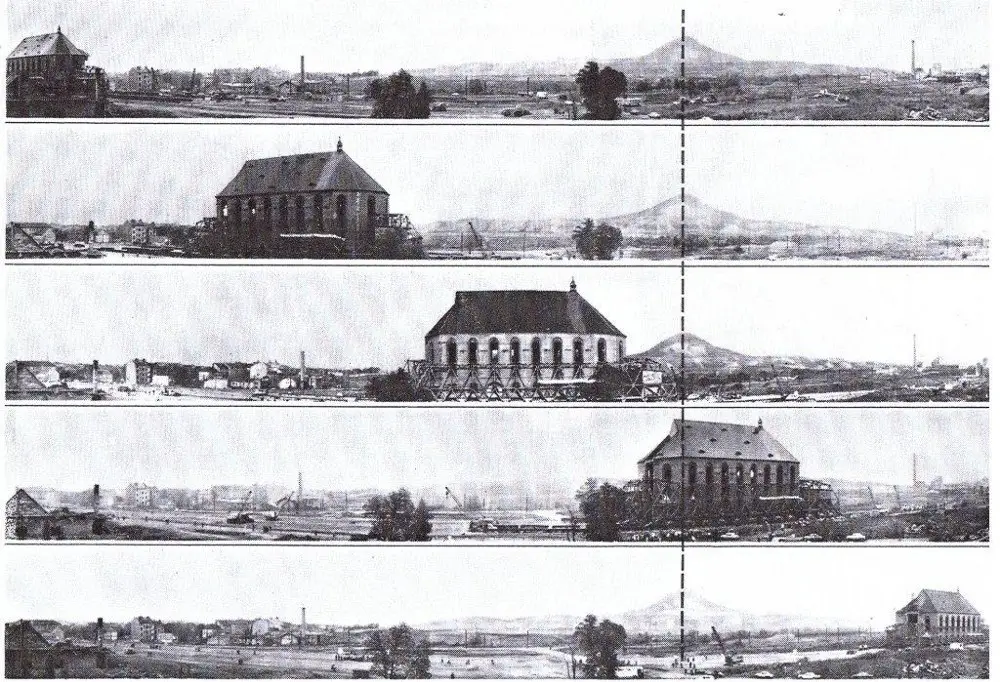

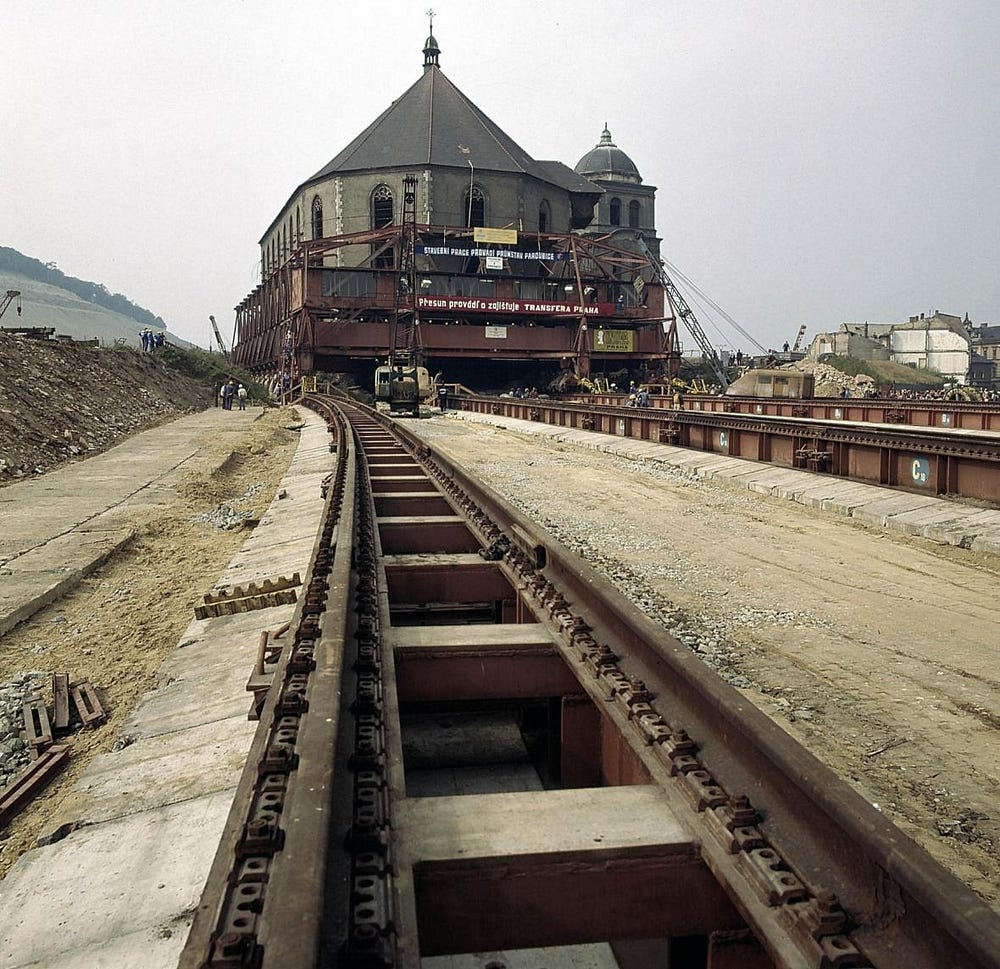

It took nearly seven years to prepare for this unprecedented feat: the church circumference, the bearing and supporting pillars were reinforced, and the church was enclosed in a massive steel cage. All the buildings that stood in the way were leveled to clear the path, and rails were installed along the way. The 60-meter-long, 31-meter-wide, and 30-meter-high church was placed on 53 trucks and, on September 30, 1975, it was time for the big move.

The Church Takes a Holiday

The transport trucks worked using computer-controlled hydraulics, as did four boom units used to pull the church. As the church moved forward on the road section, rails that had already been passed over were moved from behind the building to the front of it, allowing them to be used again.

On October 27, 1975, the church reached its new home, 841 meters away from its previous location; the story of this incredible move earned this building a place in the Guinness Book of World Records. After the lengthy move was completed, restoration work went on for another thirteen years.

The impressive accomplishment inspired others to do the same. When Bucharest faced a radical redesign in the 1980s, engineers moved whole buildings hundreds of meters away on metal tracks to preserve the Romanian capital’s architectural heritage.

30-something, born and bred in Italy. If you leave me unattended in your house I will sand down and repaint every piece of furniture you own. Can’t parallel park to save my life.