hen the Portuguese first visited the miraculous city of Benin in 1485, they were amazed to find this vast, mathematically planned, and architecturally superior urban empire in the middle of the jungle with hundreds of interconnected towns and villages and they called it the “Great City of Benin“.

hen the Portuguese first visited the miraculous city of Benin in 1485, they were amazed to find this vast, mathematically planned, and architecturally superior urban empire in the middle of the jungle with hundreds of interconnected towns and villages and they called it the “Great City of Benin“.

Benin City had full street lighting and was one of the first cities with night lighting at the time. It was covered with huge metal lamps several feet high, which became more frequent and magnificent near the royal palace. The wicks were fuelled by palm oil, which would later become the most important commodity for the British, who had a great demand for brass oil, leading to the first oil war in the 19th century, which eventually resulted in the entire area now known as Nigeria being sold to the British government by the British Royal Niger Company in 1899 for £865,000 (£108 million today), which would be equivalent to £46,407,250 today.

In 1691, a Portuguese captain Lourenco Pinto described the city of Benin as an astonishing, prosperous, and industrious city, larger than Lisbon, where all the streets run straight as far as the eye can see and the houses are large, especially the king’s, which is richly decorated and has beautiful columns. He wrote that the city of Benin is so well governed that thefts are unknown and the people live in such security that they’ve no doors on their houses.

Everyone wants a piece of exotic, valuable, and sophisticated art from Benin

The Nigerian Benin Empire was one of the oldest and most developed states in pre-colonial West Africa, dating back to the tenth century when the Edo people settled in the tropical rainforest of West Africa in what is now southern Nigeria. In the fifteenth century, the great Benin Empire stretched from Sierra Leone to the Congo.

The empire was rich in gold, iron, palm oil, and pepper, but most notable were its fractal geometric architecture and highly skilled crafts, especially woodcarving, weaving, and brass casting, which reached its aesthetic and technical peak in the sixteenth century when decorative panels and sculptures (now known as “Benin bronzes”) were produced to decorate the palace of the Oba (a name for the king) and every European visitor wanted to buy them.

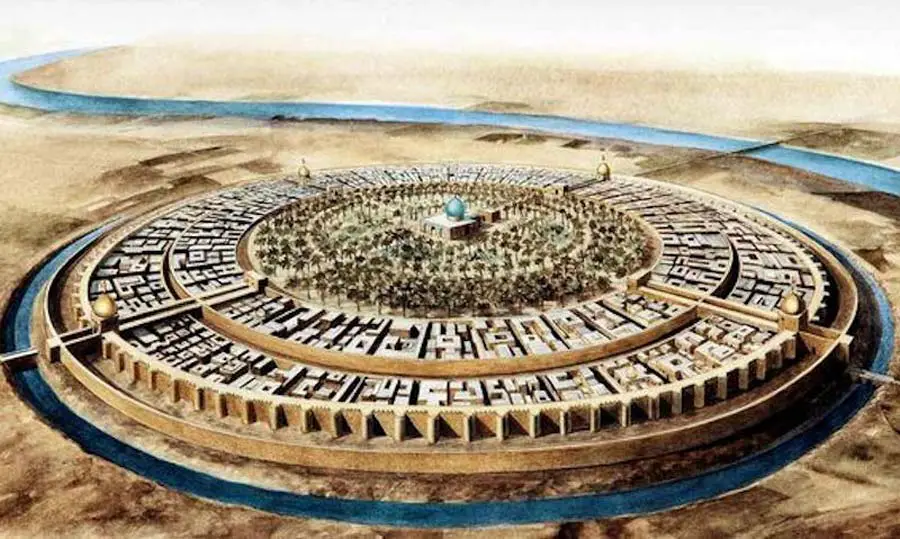

Most fascinating, however, were the marvelous man-made walls of Benin City and the surrounding kingdom, now considered a world architectural phenomenon and the greatest single structure in the world before the mechanical age. They stretched for 16 000 km and covered 6 500 square kilometers, forming a mosaic of more than 500 interconnected settlement boundaries. It is estimated that it took the Edo people 150 million hours to build the walls.

When the British took over the territory from the French and Germans at the Berlin Conference of 1884 and secured exclusive access to the lucrative palm oil trade, they did not realize the significance of Benin’s architecture, having never seen the geometric architecture and fractal design of Africa.

In line with their cultural racism and attitude of superiority, they considered this incredible master architecture to be disorderly, primitive, and completely unscientific, which, as in the case of American indigenous culture, was anything but true.

The British wrote the colonial narrative to gain complete control over the territory of present-day Nigeria

The truth was that while Benin was bursting with luxury, splendor, and security, London was dark, poor, and dirty. While Benin society was peaceful, friendly, and just, London was a dystopian nightmare of theft, prostitution, murder, bribery, and life danger. And while the kings of Benin negotiated, the British government played dirty with Western, colonial, and foreign strategies.

Towards the end of the 19th century, the Benin Empire was one of the few African empires that remained independent. Not only did the empire prosper economically, but the people were also widely recognized for their art and culture. But everything changed in 1897 when the British invaded the empire, looted thousands of artifacts, and set fire to the capital.

Three centuries earlier, the empire had established peaceful trade relations with the Portuguese, exporting mainly gold, ivory, palm oil, pepper, art, and enslaved Africans, while the Portuguese supplied them with weapons for their tribal wars and animal hunting. The south coast of Benin was important for the slave trade for centuries, and more than 10 000 slaves were shipped across the Atlantic every year.

Unlike the Portuguese, the British were only interested in the commodities, palm oil, gold, and art, but not in the slaves who had already been freed in the West when the British showed up and accused the Edo people of slave trading, ritual human sacrifice, and even cannibalism.

The 1897 Benin Massacre

When the Europeans began to abolish less profitable slavery in favor of the more profitable colonial exploitation of African states, the Kingdom of Benin was one of the last to sign the treaty with the British in 1892 after long, dubious negotiations. But even then, it refused to cooperate with the British on their trade demands.

In January 1897, the British government sent a small force of unarmed soldiers on a trading expedition to Benin. However, some chiefs feared that the expedition would disrupt their annual royal rituals and attacked the expedition against the king’s wishes. Six British officials and nearly 200 African porters were killed.

The British immediately responded by sending 1 200 soldiers armed with Maxim machine guns to take Benin. After 17 days of fierce resistance by the Beninese soldiers, the palace was burned and looted in February 1897, and the king was sent into exile. Most of the British casualties were African recruits who had been sent ahead.

The British confiscated all royal and city treasures and burnt down the entire city, while the artifacts eventually ended up in museums and private collections around the world. Some Nigerian scholars, museum professionals, and the Benin royal court are still campaigning for their return. Perhaps it is time for the British king to introduce a new ethical practice.

Today, no traces of the ancient city of Benin can be found in the location that has been built over to become the modern city of Benin. The only place where you can catch a glimpse of this amazing advanced civilization is the British Museum, which is still living well off the stolen property.

Imagine how much tourist revenue Benin could attract today if only there was a replica of the city with its wall and a few art figures. Whatever happens, one thing is certain. The new world cannot be built on unethical foundations, otherwise, it will be the same old world.

Writer and director who thinks different and does everything differently. Art enthusiast. Wandering and wondering. Until the end of meaning.

irena_curik@hotmail.com