the spring of 1944, Nazi troops killed hundreds of Italian civilians in what became known as the Ardeatine Cave Massacre. After the end of World War II, the two governments, Rome and Bonn, did not take any action to track down the killers, being more interested in political issues and not in justice.

the spring of 1944, Nazi troops killed hundreds of Italian civilians in what became known as the Ardeatine Cave Massacre. After the end of World War II, the two governments, Rome and Bonn, did not take any action to track down the killers, being more interested in political issues and not in justice.

Cold Blood in Caves

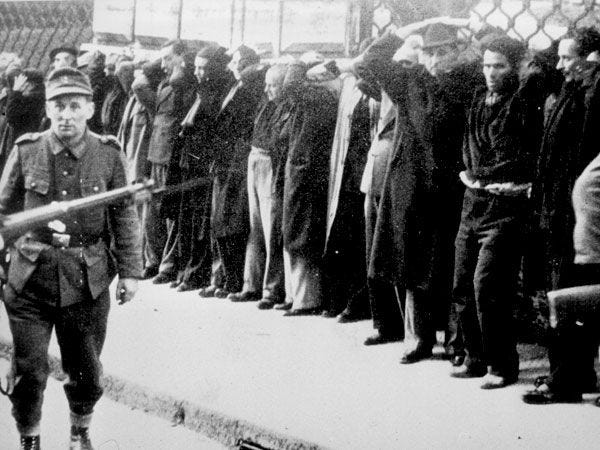

Before World War II, the Ardeatine Caves were exploited as volcanic rock used in cement production. But on March 24, 1944, production had long since ceased. On that day, several trucks with prisoners were brought there — a total of 335 Italians, the youngest of whom was only 15 years old.

The German occupiers wanted revenge for an attack that the communist partisans had organized the day before against a German unit stationed in Rome. The victims of this act of revenge were chosen at random, most of the prisoners in a Gestapo prison in Rome. None of the 335 Italians had been involved in the communist action. At 15.30, the first group of five men was brought. An SS officer was there to ask for their names and cut them off a list.

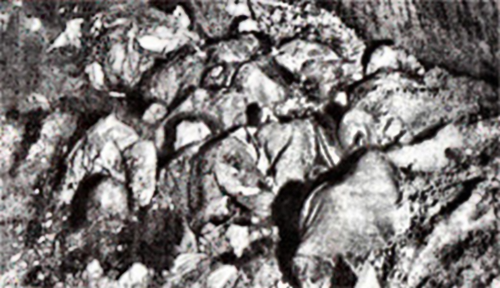

The men were forced to kneel on the cold floor of one of the caves and were shot. Then the next five men were brought. As the bodies multiplied, German officers gathered them into a pile that the next victims had to climb before they could also be killed. Because some of the Nazi officers drank a lot of alcohol during the operation and were no longer able to fire, some of the victims did not die immediately. Some suffocated under the weight of the dead above them or died in the ensuing explosion — in the end. The Nazis covered their tracks by detonating a large number of explosives in the cave.

The incident remained in the history of war crimes as the massacre at the Ardeatine Caves. After the war, it became a symbol of the German atrocities committed in Italy during the Third Reich. A memorial was erected there in memory of the victims, where Italian politicians lay wreaths annually. But although the massacre was commemorated annually since the early postwar years, neither German nor Italian officials had any interest in bringing those responsible to justice.

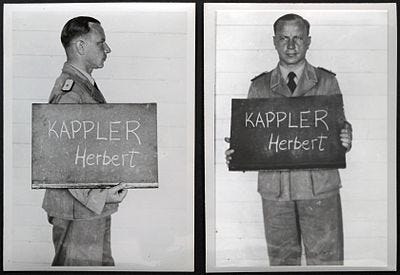

The only person punished was Herbert Kappler, the SS officer in charge of the German police and security services in Rome during the war. He was sentenced to life in prison in 1948.

Unpunished War Crime

Historian Felix Bohr tried to find out why officials were so reluctant to punish these crimes. Searching documents in the archives of the German Foreign Ministry, he discovered an impressive set of documents. The correspondence started in 1959 between officials at the German embassy in Rome and their counterparts in the Foreign Minister in Bonn. Documents show that German diplomats and Italian officials worked together to protect soldiers under Kappler’s rule so that they would not be tried. Both sides were interested in keeping the whole story in the past.

In the case of the Ardeatine Caves massacre, the initiative to leave the incident behind came from the Italian government. The first attempts to see the Nazi crimes punished were abandoned fairly quickly. Many of those to be tried lived in post-war Germany, but the Christian Democrats who ran the Italian government wanted to avoid a scandal over extradition requests. As one Italian diplomat put it:

“the day the first German murderer is extradited, there will be a wave of protests in countries demanding the extradition of Italian criminals.”

After all, Italy had been with Nazi Germany until 1943 and occupied territories in the Balkans, where hundreds of thousands of people fell victim to the violent regime installed by the Italians (and indoctrinated by the Germans).

Moreover, the Christian Democrats feared that conducting new war crimes trials could ruin Italy’s good relations with Germany, as well as relations with Chancellor Konrad Adenauer, a founding member and leader of the Christian Democratic Union in the FRG. In the end, the Italian Christian Democrats did not want to revive the memories of the anti-Nazi resistance of communist origin because the communist opposition in the country could have been advantaged.

Thus, in 1958, the concealment operation began at the Military Prosecutor’s Office, where thousands of files were closed in archives. A year later, however, civilian prosecutors began to take an interest in the Ardeatine Caves massacre. However, the action against Kappler could never be officially completed because 12 suspects could not be identified.

The Final Trial

In October 1959, Attorney General Massimo Tringali visited the German embassy in Rome. According to the documents, German Ambassador Manfred Klaiber says that Tringali has made it clear that there is no interest on the part of the Italian side, for domestic policy reasons, to bring the whole issue of hostage execution in Italy, especially the Ardeatine case, back to the public.

Therefore, Tringali said he would be grateful if German officials could confirm that none of the 12 suspects were alive or that there was no information about their whereabouts. Ambassador Klaiber, who had been a member of the Nazi party since 1934 and worked in the foreign ministry during Hitler’s time, noted that he “understood the request” of the Italians.

The request of the Italians was sent to Bonn to a certain Hans Gawlik. This diplomat also had a Nazi past: he had joined the party in 1933, had been a prosecutor in Breslau during the war, and during the Nuremberg trials, he was the defense lawyer for several SS leaders. It was not until 1968 that Gawlik revealed that he had used his position in the foreign ministry to warn former Nazis not to travel to certain countries where they had been sentenced in absentia. In light of these details, it is not surprising that Gawlik wrote to the embassy in Rome that “the current location of some of those wanted could not be determined,” adding that it is not possible to know exactly whether they are still alive.

Among those wanted was Carl-Theodor Schütz, who had ordered the executions. The former SS captain was working at the Bundesnachrichtendienst, the Foreign Intelligence Service, in 1960. Another person on that list was Kurt Winden, who, according to Kappler, had been involved in selecting the victims to be executed. He would have been easy to locate: he worked in Frankfurt at Deutsche Bank.

The trials in Rome officially ended in vain in January 1962. Years later, when almost all of the former Nazis withdrew from their positions after the war, only two men were to be held accountable for their actions. Both admitted that they took part in the massacre at the Ardeatine Caves. After the war, they lived under their real names: Erich Priebke in Argentina, and Karl Hass in Germany, from where he visited Italy from time to time. In 1998, the two were sentenced to life in prison. Meanwhile, Hass has died, and Priebke, at the age of 98, lives in Rome under house arrest. He was the SS officer who cut off the names of the victims from the list before sending them to their deaths.

Avid Writer with invaluable knowledge of Humanity!

Upcoming historian with over 30 million views online.

“You make your own life.”