very day, our conversations involve some form of persuasion. You might be having a rigorous philosophical debate about the dangers of artificial intelligence, or you might be attempting to reason with a toddler who refuses to eat their vegetables. Regardless of the situation, the art of persuasion is a useful tool to have.

very day, our conversations involve some form of persuasion. You might be having a rigorous philosophical debate about the dangers of artificial intelligence, or you might be attempting to reason with a toddler who refuses to eat their vegetables. Regardless of the situation, the art of persuasion is a useful tool to have.

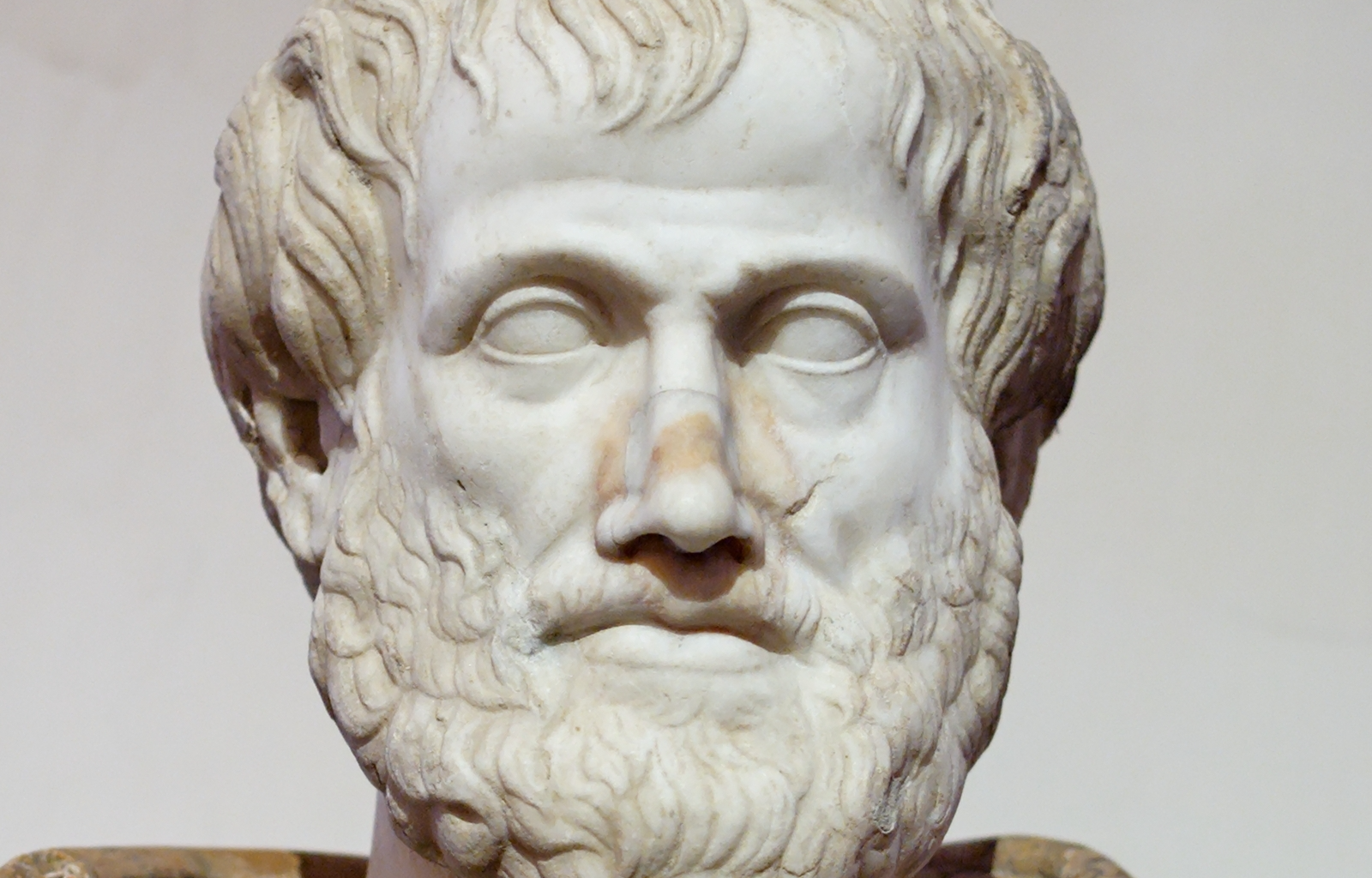

Aristotle, who is now considered one of the wisest and most influential philosophers of all time, was interested in a vast range of topics, including the art of persuasion. And like many of Aristotle’s ideas, his insights on this subject still carry a lot of value today.

Ethos

In Rhetoric, Aristotle divides the art of persuasion into three parts: Ethos, Logos, and Pathos. The first of these components is centered on the credibility of the person who is seeking to persuade the audience with their argument:

“‘It is not true, as some writers assume in their treatises on rhetoric, that the personal goodness revealed by the speaker contributes nothing to his power of persuasion; on the contrary, his character may almost be called the most effective means of persuasion he possesses.”

Aristotle makes it clear that Ethos is the most important component of the three-part method of persuasion. To put this in simpler terms, speakers should tell the audience why they can be trusted. For example, this might be the speaker’s moral character or past experiences in a particular field.

If the speaker does not prove their credentials, the audience will be less inclined to agree with the argument, regardless of how strong it is.

Logos

Logos, meanwhile, is about the argument itself:

“… persuasion is effected through the speech itself when we have proved a truth or an apparent truth by means of the persuasive arguments suitable to the case in question.”

Simply put, the argument should be backed up with facts and logic. In other words, it needs to make sense. If there’s too much idealism and not enough pragmatism, the audience will not be convinced.

Even if you’re presenting a hypothetical scenario, the laws of said scenario should match the parameters of the real world. This way, the audience will be able to follow the speaker’s argument and see the real-life logic behind the make-believe scenario.

Pathos

Pathos, on the other hand, is all about emotion:

“… persuasion may come through the hearers, when the speech stirs their emotions. Our judgments when we are pleased and friendly are not the same as when we are pained and hostile.”

Here, Aristotle is highlighting how emotions are essentially receptors, and that those skilled in persuasion will use their words to trigger specific receptors. Provided the speaker can do this effectively, the emotional response of the audience will encourage them to support the argument being presented to them.

Fear is particularly powerful, and according to Aristotle, it comes from a perception of impending evil capable of causing pain and destruction. If the speaker is able to cause fear in the minds of the audience, the argument is far more likely to resonate.

Conclusion

In essence, Ethos, Logos, and Pathos equate to the credibility of the speaker, the strength of the argument, and the emotions of the audience.

It’s a simple three-part method that is still relevant today. Politicians, lawyers, teachers, lecturers, and advisors still use this model, even if they’re not aware of it.

Whether you’re at the pub with your friends or preparing a speech for a public speaking event, this method is a valuable resource to have.

Purchase my history quiz book: https://www.amazon.co.uk/dp/B0BLFWPMKL

Contact: jacobwilliamwilkins@gmail.com