hen Anton Chekov’s reputation as a promising young author was just beginning to grow, he got a shocking review from well-known Russian critic Alexander Skabichevsky. In an article published in the Severny Vestnik Magazine (1886), Skabichevsky unceremoniously compared Chekhov to a mushy lemon that would be forgotten as soon as it was squeezed.

hen Anton Chekov’s reputation as a promising young author was just beginning to grow, he got a shocking review from well-known Russian critic Alexander Skabichevsky. In an article published in the Severny Vestnik Magazine (1886), Skabichevsky unceremoniously compared Chekhov to a mushy lemon that would be forgotten as soon as it was squeezed.

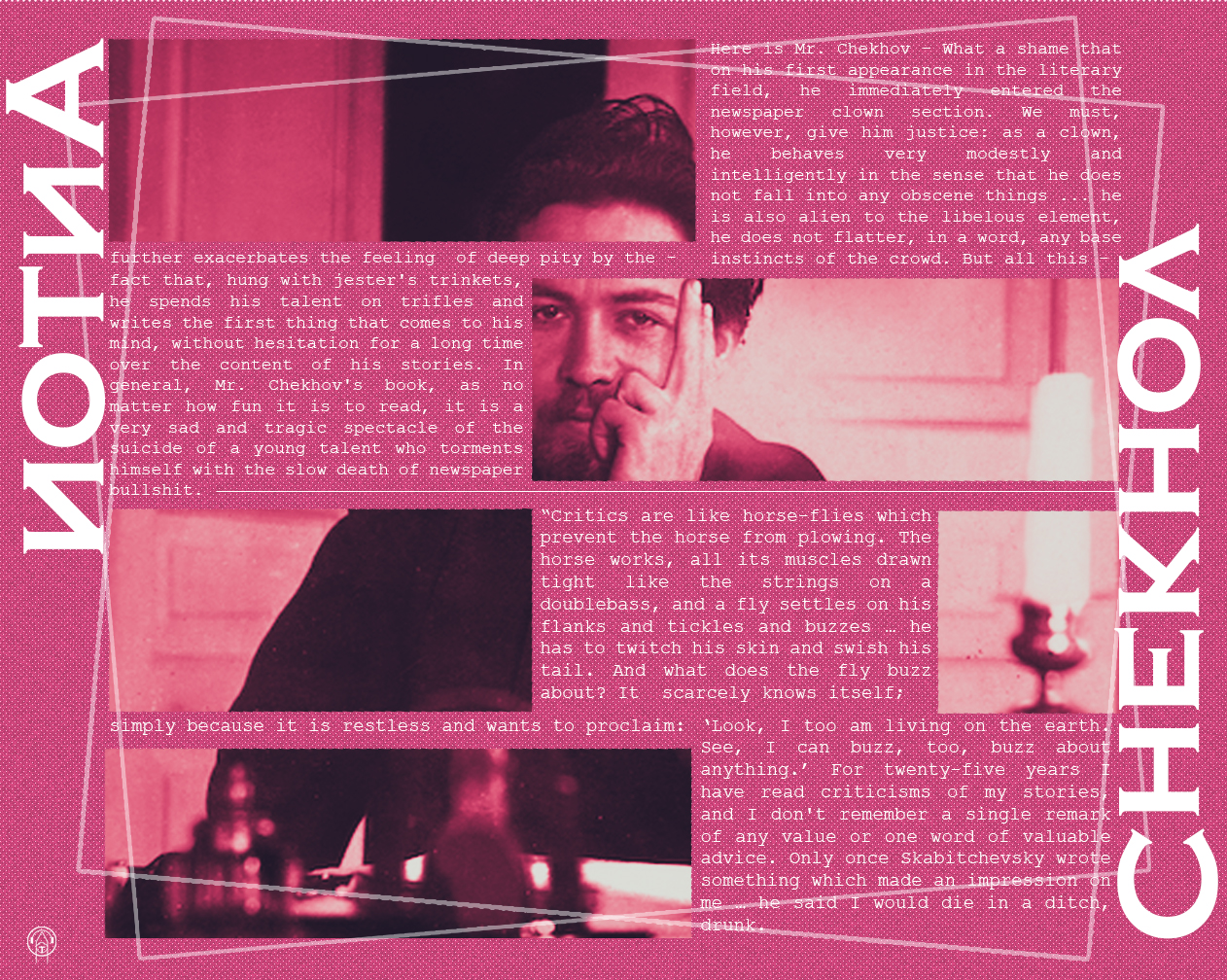

“…and, like a squeezed lemon, he must die oblivion somewhere under the fence,” Skabichevsky said in welcoming the publication of Chekhov’s book, Motley Stories, as rewritten by Igor Nikolaevich Sukhikh in his book A.P. Chekhov

Pro et Contra: Creativity of A.P. Chekhov in Russian Thought of The Late XIX – Early XX Century (2002).

Chekhov, he argued, was preoccupied with negligible and banal themes, lulled by little jokes, and, worst of all, he appears frivolous because he writes in a split second when an idea flashes through his head without much thought.

“What a shame that on his first appearance in the literary field, he immediately entered the newspaper clown section,” he added. “In general, Mr. Chekhov’s book, no matter how fun it is to read, is a deplorable and tragic spectacle of the suicide of young talent who torments himself with the slow death of newspaper bullshit.”

Although the article had little impact on Chekhov’s popularity later in life, it left him with a sense of shock that he would never forget. In a letter to his friend Alexei Suvorin (February 1893), Chekhov expressed his displeasure with Russia’s harsh, insulting, and hateful culture of criticism.

“Why must they write in a tone fit for judging criminals rather than artists and writers? I just can’t stand it, I simply can’t”.

He joked to his colleague, Maxim Gorky, that the critic’s presence was like a fly circling a plow-horse. They will buzz and occasionally tickle the horse’s body to show the world they exist. Nothing more.

Throughout decades of writing, Chekhov continued, he had read various criticisms of his work, but none of the valuable advice he could recall. Except for Skabitchevsky, of course. “He said I would die in a ditch, drunk,” Chekhov said with a smile, as Gorky wrote in Reminiscences of Anton Chekhov (1921).

Skabichevsky’s review of Motley Stories, on the other hand, provoked the young Chekhov to evaluate his authorship career. Re-examine his works, and ask himself: is he satisfied with what he has produced, both in terms of technique and profundity of the theme?

To Dmitry Grigorovich, a senior writer who later contributed to his career development, Chekhov said his book was more like a collection of gibberish, poorly written in a student style. “Had I known that I had readers and that you were watching me, I would not have published this book.”

Since then, Chekhov’s work has gradually evolved to become more in-depth. If in the first eight years of his career, Chekhov wrote an average of 56 short stories per year (1886 was his peak year of productivity with 102 stories), by the 1890s, his output had plummeted to no more than 11 short stories per year.

The Last Sip of Champagne

Like many of his works, the story of Chekov’s death presents a thin line of doubt that leaves the reader wondering: did that really happen? This is amplified by Chekhov’s biographers’ and literary colleagues’ habit of re-telling the story in different variations. A death story marked by a bottle of champagne and ice.

On July 2, 1904, as a mist of darkness began to shroud the quiet and dull Badenweiler Building (a health resort and spa in southwest Germany), Anton Chekhov felt that his death was imminent.

He then asked his wife, Olga Knipper, to contact Dr. Schwohrer, who was in charge of his care at the time. Olga then relayed her husband’s request to the two students assigned to accompany them in the next room. The two students immediately ran toward Dr. Schwohrer’s room in deft steps.

While Olga is plagued by anxiety and fear of losing her loved ones, the bedridden Orwell is now experiencing hallucinations. He was delirious and babbling incoherently. Once, he was muttering about the Japanese, and a few seconds later, he was babbling about sailors. Everything is random and meaningless.

Olga understood that she should not ignore such circumstances. Olga then placed an ice bag on Chekhov’s chest to help him regain consciousness. It didn’t take long for Chekhov to revive. “You don’t put ice on an empty heart,” he said quietly to his wife.

Moments later, Dr. Schwohrer arrived in the room. He then checked Chekhov’s condition while providing first aid as a camphor injection to stimulate his heart. There was no reaction.

Understanding his patient’s deteriorating condition, Dr. Schwohrer ordered the two students to take oxygen immediately. “What’s the use?” Chekhov interrupted. “Before it comes, I’ll be a corpse.”

Hearing Chekhov’s reaction, Dr. Schwohrer realized the man in front of him was dying. Then he took the initiative and called the hospital staff to bring them the best champagne. Dr. Schwohrer felt they needed to commemorate this rare episode by throwing a farewell party for the legendary writer.

“How many glasses?” inquired the officer.

“Three,” he yelled, “and hurry, you— hear?”

Dr Schwohrer opened the champagne and poured it into three glasses as soon as it arrived. Olga took two pairs of glasses—one for her, the other for Chekhov. Despite his helplessness, Chekov can still smile and say, “It’s a long time since I’ve had champagne.”

Those were the last words that came out of Chekhov’s mouth. Anton Pavlovich Chekhov died after taking the last sip of champagne. He died “drunk,” as if to fulfil the “curse” cast by Alexander Skabichevsky 18 years before.

The difference is that, unlike Skabichevsky’s verses, he mokshas in Olga’s arms with praise and roars of applause instead of dying by the side of a fence and being forgotten.

Passionate about history and pop culture.