ren’t you glad you don’t have to go outside, chop down trees, hack them into chunks, haul them into the house (bringing in mice, spiders, and all kinds of crawling insects) and shove them into a woodstove to stay warm?

ren’t you glad you don’t have to go outside, chop down trees, hack them into chunks, haul them into the house (bringing in mice, spiders, and all kinds of crawling insects) and shove them into a woodstove to stay warm?

Do you ever think about what it would be like to have to shovel sooty, black, dirty coal into a stove every hour to stay warm? (While breathing in coal dust that caused pneumonia and other respiratory illnesses.)

Have you ever thought about what it would be like to have to heat your home with a fire burning in the middle of the floor, smoke wafting through the hole in the roof (only after embedding its lasting odor in the fibers of everything you own?)

Yep. Me neither. At least until I read about Alice Parker.

Why we need heat — and how we got it

Heat is a basic human need. Air, food, and water, too. But being warm is crucial to life. If the body temperature can’t be maintained at a certain level, it will shut down. (Hypothermia sets in when our core body temperature goes below 95 degrees. Death results when our temperature drops below 70 degrees.)

Human beings have always sought warmth. They started using fire to cook food in 1,900,000 B.C. One hundred thousand years ago, archeologists have found that people built structures with openings in the roof because they kept fires burning inside to stay warm and cook their food.

The need for heat was consistent and great, so throughout history, humans have worked to get it easier and faster.

By 3000 B.C., settlers in the Slavic country of Romania had developed braziers to help warm their homes.

Half a century later in ancient Rome, Greeks designed a radiant heat system. They put pipes in the ground that circulated air that had been heated by a fire.

Sadly, when Rome fell, so did a lot of its advancements, and the early central heating they developed disappeared.

Some like it hot…

It took another thousand years or so before radiant heat made a comeback. European monks started using wood-burning furnaces to heat water from a diverted river.

Four hundred years later, a Frenchman did something that dramatically improved the heating ability of fireplaces everywhere. It seems simple now, but it’s always that way with progress. In 1624, Louis Savot improved the heated airflow output from a fireplace by building a raised grate.

(Amazing, isn’t it, that something we take for granted, the simple fireplace grate, drastically improved the heat of a home?)

In 1741 or 1742, one of America’s premier statesmen, inventors, and writers, Ben Franklin, created the Franklin Stove. The stove that bears the name of its creator was basically a metal fireplace with air vents in the back. The Franklin Stove was more efficient than the open-brick fireplaces of the past because it burned less wood and emitted much less smoke.

In 1883, the creator of the light bulb, Thomas Edison, invented an electric heater. Two years later, a man named Dave Lennox designed and sold the first riveted steel coal furnace, and much of the nation switched from wood-burning to coal-burning heat.

By the late 1800s, radiators were commonplace. Made of low-cost iron, these radiators made it possible to team with a coal-fired boiler that would heat water and push hot steam out of the radiators to heat homes.

Enter Alice Parker

Alice Parker should be a household name. She should have recognition for her exceptional ability to see, dream, design, and follow through on an idea. Instead, few people have any idea that an African American woman at the beginning of the 20th century, forever altered our world. Alice Parker created and patented the modern central heating system.

Born in 1885 in Morrison, New Jersey, Alice Parker was a smart, educated, woman. In 1910, records show that she graduated with honors from a co-ed, traditionally black, Howard University Academy that had been founded in 1866.

Very little information exists about the life of Alice Parker. Based on census records of the time, we do know that she spent time as a cook in a New Jersey home where her husband served as a butler.

Maybe while she served as a cook at the home, she was cold all the time. Maybe she missed the academic rigor of her earlier studies. Maybe the master or mistress of the home asked her to think about what she could do to improve the heating. Maybe her brain just couldn’t stop thinking about ways to solve problems.

All we know is that Alice understood that a fireplace was not enough by itself to heat a house. She confronted the problem by engineering a gas-powered furnace and a system that would distribute heat evenly through individual ducts. She designed a system that used cold air, pulled it into a heat exchanger, and pushed the resulting warm air into the ductwork. Creating a system based on individual ducts allowed Alice Parker to “zone” her heat and control where it went.

Amazing woman, inventor, and trailblazer

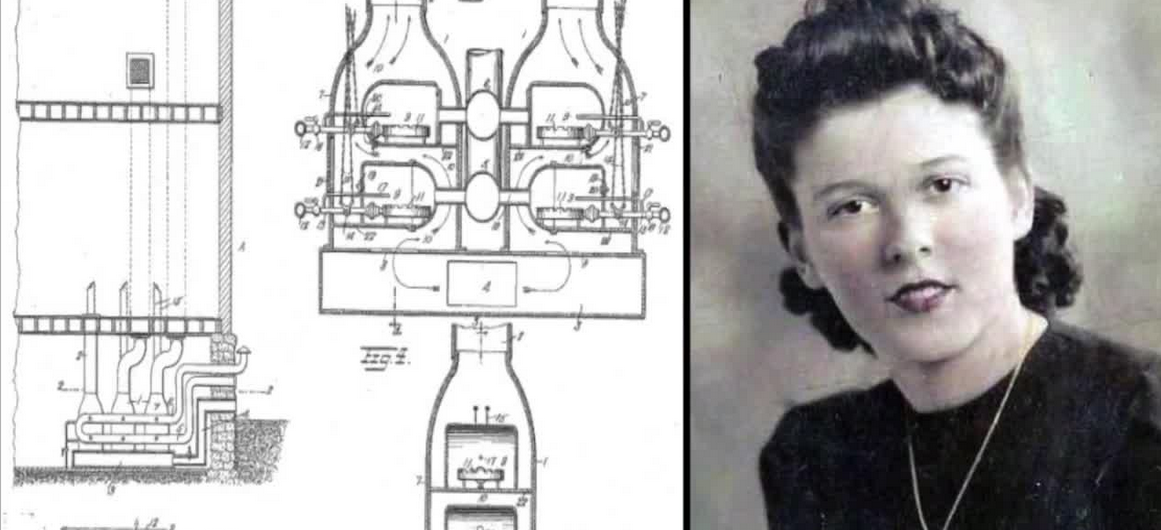

In 1919, decades before Women’s Liberation and the Civil Rights movement, Alice Parker, a black woman, filed for a patent on her furnace. On December 23, 1919, her patent was granted, No. US132590A.

Alice Parker’s contribution to modern HVAC is invaluable.

Her furnace lessened the risk of house and building fires prevalent at the turn of the century.

Her design paved the way for efficient home heating by using gas instead of wood and coal.

Her invention instigated others to refine zone heating, thermostats and forced air furnaces.

One hundred years after Alice Parker received a patent on her furnace, the National Society of Black Physicists honored her invention as “a revolutionary idea for the time that conserved energy and paved the way for central heating systems.”

Forgotten, little-known Alice Parker

Someone who contributed so much to our modern conveniences and quality of life should be remembered.

However, few records exist that describe Alice’s life. Even the date of her death is unknown. Some people believe that she died in 1920, and in a strange irony, suggest that her death was due to thermal shock, a condition that occurs when there’s a large and rapid change of temperature to the body.

In fact, we don’t even know what she looked like. The photos that come up on internet searches are not accurate. The first seems to be a white woman in clothing more suggestive of the 1940s or 1950s. She’s clearly a different person than the Alice Parker who engineered central heat.

The second photo cited as being Alice Parker is, in actuality, a woman named Marie Van Brittan Brown, developer of the home security system, (another article altogether.)

Just goes to show you that you can’t trust everything you see on the internet!

Sadly, most people don’t know what Alice Parker did for our world.

But if you appreciate having quick, clean heat, controlling temperatures in different rooms, or using gas instead of chopping wood or shoveling coal into a hot metal stove, then you need to thank the designer of our modern central heat systems.

Melissa Gouty has been a writer since she could hold a pen. Author of The Magic of Ordinary, she is a former newspaper columnist, English professor, and award-winning entrepreneur. Curious about everything, she writes about history, books, marketing, gardening, and writing.