a politics addict, not only am I interested in my country’s domestic politics, but also in international politics. Each country differs in terms of culture, society, history and institutions. However, there’s one factor that makes all democracies similar; that is, the existence of two or more parties that are ideologically positioned on a continuum that goes from Left to Right. In England there are Labours and Conservatives, in the US there are Democrats and Republicans.

a politics addict, not only am I interested in my country’s domestic politics, but also in international politics. Each country differs in terms of culture, society, history and institutions. However, there’s one factor that makes all democracies similar; that is, the existence of two or more parties that are ideologically positioned on a continuum that goes from Left to Right. In England there are Labours and Conservatives, in the US there are Democrats and Republicans.

If we focus on each country’s political language rather than its party system, then we’ll find out that there is also another feature shared by nearly every western democracy. Each country has its own political language, which is clearly shaped by its historical roots. For instance, an Italian politician is much more likely to talk about the Catholic Church than a British one. However, as I’ve already said, there is also a strong similarity. When these countries experience times of social and political tension, we are likely to hear lots of undue references to Fascism.

What is Fascism? Have you ever thought about that? This word is used quite frequently in modern Politics, but does it really make sense? Politicians make use of several distortion tactics in their speeches. One of them is called “Name-Calling”, by which a politician attacks her/his rival by linking her/him to a negative symbol. Here, “Name-Calling” is represented by the word “fascist”, whereas the negative symbol is clearly Fascism. Still, does it really make sense to use this word and this symbol? The answer, to which I’m going to bring evidence, is no.

The problem is that, all around the world, several politicians usually just say something like, “He is a fascist,” and then drop the mic, as if nothing more needs to be said. But there is something more that has to be said. If a person attacks someone else by labelling her/him as a fascist, then s/he should be able to explain what being a fascist means. Otherwise, the attack will be no more than mere speculation.

In 1946, George Orwell published an interesting essay called “Politics and the English Language”. In this essay, Orwell criticized several inaccuracies of the written English of his time. He dedicated some lines to the word “Fascism” too. According to him, ”the word Fascism has now no meaning except in so far as it signifies ‘something not desirable’”. Hence, Orwell considered that the word “Fascism” had been deprived of its real meaning. He went on saying that:

The words democracy, socialism, freedom, patriotic, realistic, justice have each of them several different meanings which cannot be reconciled with one another. In the case of a word like democracy, not only is there no agreed definition, but the attempt to make one is resisted from all sides. It is almost universally felt that when we call a country democratic we are praising it: consequently the defenders of every kind of regime claim that it is a democracy, and fear that they might have to stop using that word if it were tied down to any one meaning.

Historically Speaking

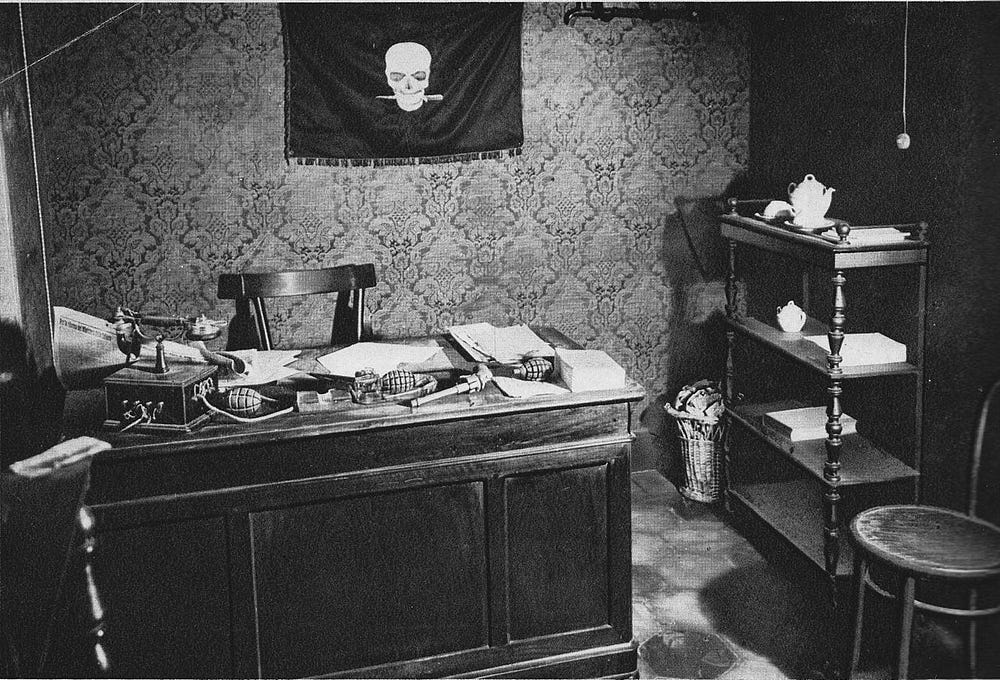

There’s an essay called “The Doctrine of Fascism” written by Mussolini in 1932 as a sort of fascist manifesto. It would be wrong to compare this essay to Marx’s and Engels’ “The Communist Manifesto”. They are different in terms of lexicon, style and purpose. Instead, it is much more reasonable to compare “The Doctrine of Fascism” to the “Mein Kampf”. Both are essays and not manifestoes. However, there are also a few differences. I will analyze just a couple of them.

- First of all, the “Mein Kampf” was published in 1925 (eight years before Hitler seized power in Germany) while “The Doctrine of Fascism” was published in 1932 (ten years after the beginning of Mussolini’s presidency). The former was aimed at describing what Hitler would have done once in power; the latter, instead, was aimed at providing an ideological reason for what Mussolini had already done in office. Just to make a simplistic example, we can say that, as far as Nazism is concerned, the book was published before the movie; instead, in Italy, the book was published after the movie.

- When Hitler’s dictatorship started, the “Mein Kampf” became a sort of sacred text. In schools, it was part of the curriculum. Whenever a couple got married, bride and groom were given a copy of it by the State. Each soldier was given a copy as well. Conversely, the distribution of “The Doctrine of Fascism” was nearly inexistent, as it was just an article in the “Treccani”, an Italian-language encyclopedia. Mussolini didn’t think that reading that essay should have been compulsory.

Fascism as an Ideology?

By this point, it is reasonable to wonder whether Fascism was backed by an ideology or not. Merriam-Webster gives three definitions of “ideology”; the most useful for the purpose of this article is the second one: “[Ideology is] the integrated assertions, theories and aims that constitute a sociopolitical program”. This definition implies the fact that this body of theories and beliefs is immutable; or, at least, that the key principles of the ideology do not change over time. For instance, if you are Catholic, you will always believe in the existence of God. Perhaps you will change your opinions towards same-sex marriage, as the world we live in has finally developed; but you will never deny the existence of the Trinity.

What are the key principles of Fascism, then? We have already seen the fact that Italian Fascism didn’t have a manifesto, nor a book. Where can we find these principles? The answer is that we have to derive them from Mussolini’s life. This is because Fascism — and this is the main thesis of this article — was just Mussolini’s Fascism. Hitler’s was Nazism; Franco’s was Francoism. It follows that, if you attack a politician by saying s/he is a fascist, then you are saying that s/he is an Italian man born in 1883 who ruled over Italy from 1922 to 1943. It sounds quite weird, doesn’t it?

It might be argued that Italian Fascism was just a sort of paradigm. But still, what is this paradigm like? Can we confidently say which were Mussolini’s thoughts on race or his ideas on nation? These are the two themes I’m going to analyze, as they are the typical themes one refers to when s/he uses the word “Fascism” nowadays. However, the same analysis is valid for any other theme.

Mussolini’s Ideas on Race

Fascism and racism are usually deemed bound to each other. According to many people, if someone is racist, then s/he is also fascist. However, this is clearly wrong. There are thousands of events, in History, when someone was discriminated, or killed or deported, just because of her/his race. The majority of these events took place before 1919, the year in which Fascism was created by Mussolini. Obviously, racism spread around the world long before Mussolini created the Fasci Italiani di Combattimento.

Now, let’s reverse the reasoning. That is: if someone is fascist, then s/he is also racist. From a logical perspective, this is much more plausible. However, I’m going to show you that this is wrong as well. Remember that I’ll stick to Italian Fascism. To me, Italian Fascism and Fascism are the same thing, as I’ve already said, but I’m going to repeat it throughout the article just to be as clear as possible.

The aim of this article is not to prove that all beliefs about Fascism are wrong, the aim is to bring evidence to the argument according to which we cannot confidently say what Fascism is. There were multiple Fascisms. However, all of them were embodied by Mussolini and, to a larger extent, by the Italians who lived during Mussolini’s dictatorship.

What about Mussolini’s thoughts on race, then? It might be uncomfortable, but in his first years as President of the Council of Ministers, Mussolini was not racist at all. Usually, a fascist’ racism is believed to be addressed to Jews. However, in 1920 Mussolini published an article on “Il Popolo d’Italia”, the newspaper he edited, where he wrote that:

In Italy, there is absolutely no difference between Jews and non-Jews; in all fields, from religion, to politics, to weaponry, to economics… the Italian Jews have the new Zion here, in our adorable land.

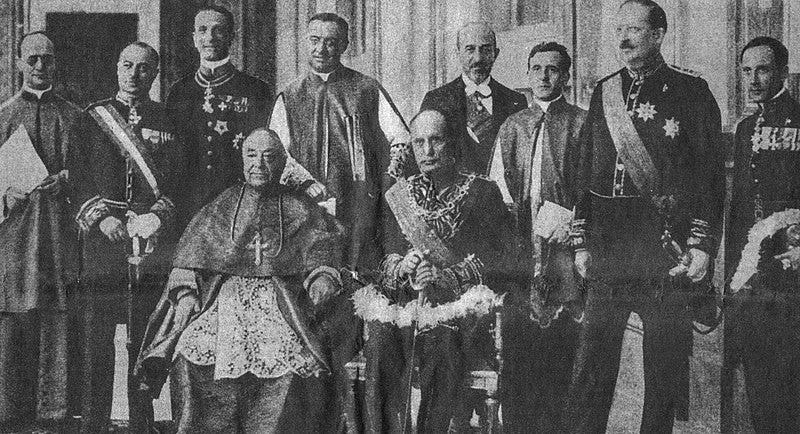

It might be argued that this was Mussolini before he took power, then everything changed. Anyway, this is not totally correct. In 1929, the Kingdom of Italy and the Holy See reached an agreement to settle the “Roman Question”. Mussolini declared Catholicism to be the official religion in Italy. When he delivered a speech to the Chamber of Deputies to explain the content of the “Lateran Pacts”, he said that:

It is ridiculous to think, as somebody said, that the synagogues should be closed. Jews have been in Rome since the time of the kings. […] They were 50,000 in the days of Augustus and they asked to cry on Julius Caesar’s body. They will remain undisturbed.

Then, from 1938 to 1943, Mussolini promulgated the “Racial Laws” to enforce racial discrimination in Italy. They were directed mainly against the Italian Jews. It is commonly acknowledged by historians that they were due to Hitler’s influence on the Italian dictator, but this is not that important for the purpose of this article. What’s important, here, is the fact that Mussolini started by ruling Jews out of the public administration and, eventually, he sent them to concentration camps.

What is the right view of a fascist towards race, then? How can we confidently say that the “true” fascist discriminates ethnic minorities? At the beginning of his dictatorship, Mussolini didn’t do that at all. If you want to read more about this topic, take a look at another article I wrote, called “Hitler and Mussolini, a Love-Hate Relationship”.

Mussolini’s Ideas on Nation

From 1922 to 1943, Mussolini’s ideas on the Italian nation were pretty much the ones we would expect. Throughout this period, Mussolini pursued the myth of the Roman Empire. He believed that Italy should have had an empire. This is the reason why the Second Italo-Ethiopian War was launched in 1935. This war of aggression resulted into a massive political success, as Fascism reached its peak of consensus; but it was also a huge economic failure, as Ethiopia was far from being a rich country. When the League of Nations imposed economic sanctions on Italy because of the conquest of Ethiopia, Mussolini delivered a speech to the Chamber of Deputies in which he talked about Italy as the victim of international conspiracies.

In 1943, after Mussolini’s capitulation, he was rescued by German paratroopers from his imprisonment in Gran Sasso massif. Brought in Munich, Mussolini met Hitler. Even if Mussolini considered his political experience ended, the Führer forced him to go back to Italy in order to take control of the Northern part of the peninsula. However, Mussolini was not ruling anymore. The Italian Social Republic was no more than a German puppet state. The Italian dictator was pretty aware of this.

Hence, what is a fascist’ ideas on nation? Are they similar to Mussolini’s original ones? If so, can we confidently say that, when Mussolini accepted to head a German puppet state, he wasn’t a fascist anymore?

What I’ve been trying to explain is that Fascism was just the story of a man and the people who decided to follow him. It is impossible to say correctly which are the ideas of a fascist. I’ve analyzed race and nation, but the same twists can be found in Mussolini’s attitudes towards political rivals, urbanization, and so on. It might sound weird, it might be uncomfortable, but from 1922 to 1943 the majority of the Italians simply decided to follow the moods of a single person. When you say that someone is fascist, then, what do you mean?

History, Politics & Economics – A place for uncomfortable truths.

michelecaimmi98[at]hotmail.com