hen we think of the United Kingdom, pictures of the great empire that once was pop into our heads. The British Raj, the Thirteen Colonies, at one point ⅓ of the world was under some kind of British control. What we don’t think of is the three undeclared wars between Britain and Iceland between the years 1958–1976. The Cod Wars were fought between the Icelandic coast guards and the Royal Navy, and every time conflict arose between the two powers, Iceland would win. It is safe to say that it was an embarrassing time for the Royal Navy and the United Kingdom. But how did a small island nation manage to beat back the world’s most renowned navy 3 consecutive times?

hen we think of the United Kingdom, pictures of the great empire that once was pop into our heads. The British Raj, the Thirteen Colonies, at one point ⅓ of the world was under some kind of British control. What we don’t think of is the three undeclared wars between Britain and Iceland between the years 1958–1976. The Cod Wars were fought between the Icelandic coast guards and the Royal Navy, and every time conflict arose between the two powers, Iceland would win. It is safe to say that it was an embarrassing time for the Royal Navy and the United Kingdom. But how did a small island nation manage to beat back the world’s most renowned navy 3 consecutive times?

Background

British fishermen have been using the water around Iceland for hundreds of years at this point to fish cod. Fish and chips being one of Britain’s staples, a solid supply of cod was required to feed the demand of the British populace. As a result, the British fishermen took more and more of the dwindling supply of cod in the Icelandic waters.

Iceland’s economy was so fishing-focused that this process resulted in a sharp drop in its economy, up to 20% at its peak. This forced the hand of the Icelandic government into action.

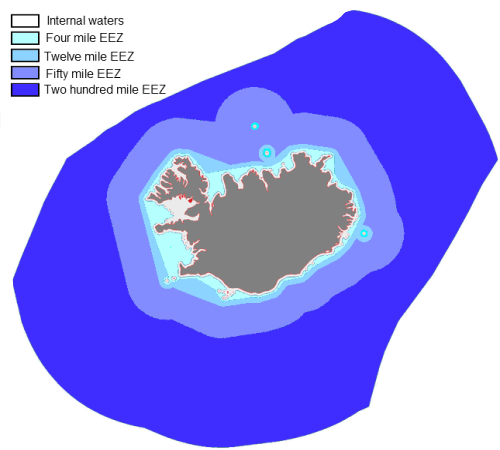

In the 1950s, a treaty was signed that allowed all nations to have control of water up to 3 miles away from their coast. This would give the Icelandic government an idea.

Iceland would push this claim to 4 miles, then to 12 to counter the British fishermen encroaching into their fishing waters. Britain would go on to ignore this as to them Iceland seemed so insignificant, with a population of 150,000~ people at the time, they seemed to pose no threat to the once-great United Kingdom. They would go on to regret this decision.

The First Cod War

The first instance of conflict between the nations came about when the Icelandic coast guards tried to detain a British fishing trawler in 1958. They had to retreat as not soon after they converged onto the trawler, a Royal Navy ship approached, but a message was sent with this action. Iceland was not afraid of the UK.

What followed was 2 years of both navies firing warning shots at each other, but not hitting ships. More of a show of power rather than an instigation for war. In 1961 Britain had enough, and with its Navy budget being stretched due to the scaling back of the armed forces in that time period, they drew up a treaty with Iceland.

The United Kingdom would recognize the 12-mile sovereignty of Iceland over the waters near their coast in return for British fishermen being able to fish in those waters between the months of October and December. This ended “The First Cod War”, with the victors being Iceland.

The Second Cod War

This ‘uneasy’ peace between the two countries would not last long as in 1971 Iceland was having the same problems as before. British fishermen would flock to the Icelandic cod fishing zones in the months they were permitted, which depleted the fish stock in the regions close to Iceland massively, tanking their economy.

The newly elected Icelandic government in 1971 wanted to change this to turn around the country’s failing economy. As a result, they declared that Iceland had exclusive rights to all fish within 50 miles of the Icelandic coast. This went on to upset many countries whose fishermen operated in that area, including the UK, West Germany and Denmark, who all used those waters before this point.

Denmark had a further reason to be upset as it saw this extension of Icelandic sovereignty as an encroachment on Danish control over the Faroe Islands. The United Nations would decide in favour of the 3 larger powers rather than the small North Atlantic island. This would start the Second Cod War.

Iceland ignored the UN’s decision on the matter and started firing on foreign fishing vessels which encroached on the newly defined Icelandic-controlled waters. In response, the United Kingdom would send in the Royal Navy, which was ordered only to engage if fired upon by the Icelandic coast guards.

This gave way to a kind of medieval style of warfare where both countries’ ships would ram each other in order to not ‘fire the first shot’, which could’ve been considered an escalation of the conflict. Even though the Icelandic navy was heavily outmatched by the Royal Navy, this didn’t stop the continuous ‘kamikaze-style attacks from both sides.

Seeing that the war wasn’t going their way due to the heavy mismatch in the power of the two navies, Iceland backed down as their last resort. Threatening to leave NATO. With England not wishing to set off a chain of events that might mean the end of NATO, especially important due to the Cold War going on at this time, they backed down.

It was agreed that Iceland would have control of the waters within 50 miles of their coasts only if British trawlers could return in 2 years and start fishing again in Icelandic waters. This was fine until the 2 year period ran out and British ships returned, which gave way to the Third Cod War.

The Third Cod War

This time Iceland was determined to extend its hegemony over its nearby waters and therefore claimed all of the waters within 200 miles of their coast as Icelandic sovereignty.

This once again gave way to the medieval ramming tactics being used between the two navies as to not escalate the conflict by introducing cannons to the fighting.

In 1976 Iceland would break international relations with the United Kingdom. With the fear that Iceland would leave NATO and fall under the influence of the USSR and join the Warsaw Pact, the US pressured the UK to resolve the conflict quickly.

As a result, the United Kingdom acknowledged the economic claims of Iceland over the waters 200 miles away from their coast which allowed both countries to start mending their international relations, giving way to the end of the Cod Wars with all three conflicts ending with Iceland being the victors.

Even when heavily outmatched both economically and militarily Iceland still stood up to one of the worlds great powers and won every time through a mix of diplomacy and political outmanoeuvring.

This case study has been used in universities as an example of asymmetric bargaining in the study of international relations as there are many lessons to be learnt from the scenario, with the main take being “where there’s a will, there’s a way”.

Student of Philosophy, Politics and Economics. History fanatic. Contact: aneculaeseicg@gmail.com