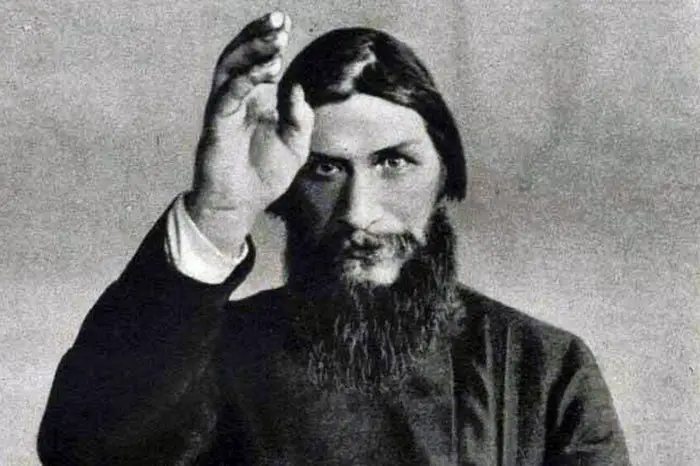

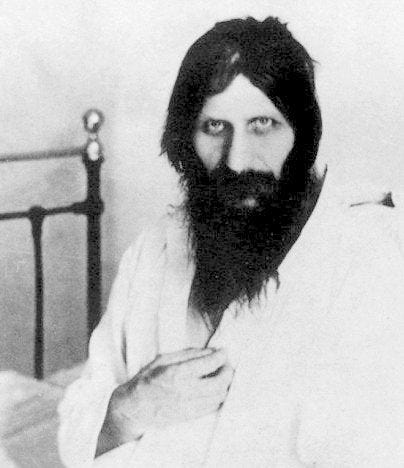

he one who has shown as the angel and satan, who juggled with the Bible, but also with the Pauline Laws, which could be found in the aristocratic alcoves, but also in the Siberian log houses, established his own religion — Grigori (“Griska”) Yefimovich Rasputin. A mystery that stubbornly remains a mystery. Rasputin, the merchant of souls, whose name is confused with the end of Czarist Russia. Even to this day, Russia is trying to hide this man’s history from the rest of the world, at the same time, many do not know about the controversial as well as mysterious life of Rasputin.

he one who has shown as the angel and satan, who juggled with the Bible, but also with the Pauline Laws, which could be found in the aristocratic alcoves, but also in the Siberian log houses, established his own religion — Grigori (“Griska”) Yefimovich Rasputin. A mystery that stubbornly remains a mystery. Rasputin, the merchant of souls, whose name is confused with the end of Czarist Russia. Even to this day, Russia is trying to hide this man’s history from the rest of the world, at the same time, many do not know about the controversial as well as mysterious life of Rasputin.

It all began in the spring of 1917, so-called the “Spring of peace and war”. The Taurida Palace was empty, devastated, and now inhabited by cravat. The imperial family had been banished and left behind angry and disoriented people. He didn’t know what was going on, but he was fine. The euphoria of the revolution was combined with hesitation. Above all, hope prevailed. About the beginnings of the world, we wrote long ago: “Think about what times we have a part! Only once in eternity do such wonderful things happen. A freedom that came upon us from an accident, from a misunderstanding. ”- this is how Iuri Jivago marveled.

Russia wanted to move to a western democracy — this was how the intelligence had read that it was a popular uprising, that the demoralizing paradise would settle, and in the new state only milk and honey would flow. A group of people gathered quickly and said, we will show you justice! It was the Provisional Government. But first of all, the culprits — in word or deed — of the old regime had to be brought before the law. From the first senior Czarist officials to the last imperialist peasants, they were searched and arrested, their trials being open.

The Provisional Government’s Extraordinary Investigation Commission was the supreme authority dealing with those who were guilty of tsarism. In a short time, Fortress Peter and Paul, the Russian Bastille, had become helpless.

Section XIII

Files over files, dozens of indictments. One subject was meant to stand behind closed doors, to talk about him in a whisper, in a brightly lit room. As a symbol, as a warning, it was called Section XIII. And he dealt with “investigating the activity of the dark forces”. The case prosecutor had been brought from hundreds of kilometers away, F.P. Simpson, former president of the Kharkiv Court of Appeal. And three other prosecutors subordinate to him, Vladimir Rudnev, Tihon Rudnev, and Grigori Girchici, were also brought from the remote provinces of Russia.

Why bother for a case when Petrograd was full of law enforcement? To prevent the recent past from affecting their objectivity and integrity. The number with misfortune, XIII, had to bring to people the answers, it had to bring peace to the living. But how could this be done when it is said that “only the dead are good”? They lit a candle in front of an icon and worshiped three times, as if by prayer. Rasputin!

Who was this man whose name was on the lips of all shadows and heard on every corner, creating hysteria on the street and panic among officials and secret services? Only now, when the dry-eyed man no longer existed, did people have the courage to know him. The Russians created the tragedy, and enjoyed it, and gave it a name: Rasputin.

Who was this saint with healing powers, this Antichrist? Who was the drunkard and the drunkard, the trusted advisor to the imperial couple? Who was the preacher of the gospels and the scriptures, this illiterate with the book of prayers to the believers?

Who was the fatal man, dressed in a red silk shirt and a coat of samurai, this man with no beard and no manners? And how did anyone get nowhere to write the epilogue of Romanovs, a curse as a forecast? For him, for Rasputin, a man who incited the whole of Russia, and not only, the Provisional Government has overhauled all the archives, all the safes and especially has gathered all the small and important who could answer the questions.

Everything looked like a cheap tabloid, like the evening gossip in front of the gate, only now the questions were asked on one side, and the information was written, stamped, and filed. They went to the land of the outlaws, in the Siberian taiga, from where they brought old people to the capital, but who had met Rasputin. Priests and monks were brought, who opened the door to salvation for the troubled young man.

Peasants with blooming fairy tales, baronies with creepy skirts, women with crinkled clothes, princesses with veils and beads, all — not a few — told the prosecutors about the incomprehensible charm of the man devoted to the land. Officials came to the back door, as is still the custom: a prince, a military man, a foreign agent or a Russian spy. All one by one, all mobilized to gather information about the man who had intrigued an entire country and whose reputation was known all the way to the West.

The true life in Empirical Russia

In the heart of Russia, where evil almost always wins. Where human settlements are emptied only by smoke coming out of baskets or by the bell sound of churches. Where the ice began to be broken only at the end of the sixteenth century, under the terror of Ivan the Terrible. You walk a lot and you see different people, but the frost has made them brothers. Go through the Ural mountains and discover that Andrei Rubliov’s world has remained the same. Pokrovskoe village, Tobolsk prefecture, was inscribed on the map somewhere during the Great Catherine, but it seems that the modern period did not reach the Siberians.

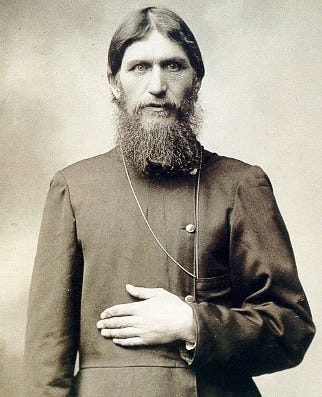

Here, on the banks of the Tura River, among the weak angels, begins the story of Rasputin. The documents say that on January 9, 1869, Efim and Anna Rasputin became parents; and that one day later the little boy is baptized at the village church. No comet passed through the sky, and no children with iron teeth or six-legged dogs were born then, as it were. Only so: every year on January 10, the Orthodox Russians celebrate St. Gregory of Nyssa, the nickname “philosopher and mystic.” So, in his honor, the child was named Grigori. The Rasputin family had long been mourning at the gate, for before Grigori came to the world five children had died before they took the first steps. Later, the two husbands had another daughter at the wedding of her brother.

Rasputin’s friends remember that he was a withdrawn boy, not communicative at all — he started talking at two and a half years ago, and when he came to the Court of Law he did not have a coherent speech. These were the times of simple people when education was only what you learned at home and on the street — only 20% of the Russian population had an education. They were born as if they were resigned. They did not know the book, but they knew that the will of God should not be called into question. The Sudba was telling her the implacable fate. There were those who, beyond beaten skin and alcohol-soaked character, believed in signs and wonders. And often, deep down, the Siberians considered themselves superior to the European Russians. They educated Rasputin, but they also rejected him.

From his adolescence he shared his father’s love for vodka — after a day’s work, a night of drinking was appropriate. As in many cases, the excess of alcohol causes the consumer to cross the barrier of common sense, and not only, even in the case of Efimovici — the boy of Efim — he did not go down as usual. She was screaming as she held her hooves, she swore at the passing passersby, clinging to girls, and began to kiss them with fire. And although in the Russian provinces, where neither the great Peter or Catherine succeeded in abolishing feudalism, such scenes were the order of the day, Rasputin kept the billboard as the villain of the village.

Despite his reputation in the village, the young man was also known for his connection with the deity. Some skeptics, others frightened rightly, the people of Pokrovskoe told how one evening, when several of his father’s friends were invited home, he heard that a poor man in the village had been stealing his horse. On one occasion, Rasputin stood up and indicated the thief as one of the group.

It seems that his vision or intuition did not deceive him. From time to time, he would leave with his family on small pilgrimages to nearby monasteries, one of which he loved — the Znamensky place of worship near Tobolsk. This is why, in the summer of 1886, near the majority, Rasputin asked for permission to go there alone. He was near the Assumption of the Virgin Mary when the young pilgrim met Praskovaya Fedorovna Dubrovina, with whom he fell in love with. The 20-year-old girl, blonde and with brown eyes, was more than Rasputin could have wished: she accepted his rebellious nature and strongly believed that he had grace in the church.

On February 2, 1887, the two married and, for a period, according to tradition, moved to the groom’s house. At that time, an epidemic of whooping cough haunted Siberia. The mortality rate among children was alarmingly high, but no one complained — so was the Lord’s will. Neither did Grigori’s fresh family escape: of the seven children they had, only three reached the age of maturity: Dimitri, Maria, and Varvara.

Road to Divinity

The fact that he had founded a family did not mean that Rasputin had been on the fence. Even worse. His neighbors say he was cheating on his wife, stealing even the bread from the house, to exchange it for a drink, and the scandals were taking place. Any crime, no matter how small, involved Rasputin. “People were blaming me when something was wrong, even if I had nothing to do with it,” he would later complain.

His neighbor, Kartavtsev, confessed that he once caught him stealing boards from his grade. Rasputin was scared that he was caught and wanted to hit the owner with the ax. The latter, in order to defend himself, struck him in the face with a plank, following the impact, permanently leaving a bump on one side of his forehead. Considering this last event, but especially because he was a harmful person to the community, people decided that for a period, Rasputin would be sent into exile. Instead, he came up with a better solution: to go on a pilgrimage. It was the spring of 1897, Rasputin was 28 years old and started on the 500-page road to St. Nicholas Monastery in Verkhoturye.

It was his way to God. Rasputin was honest with the villagers, but especially with himself. It was a self-penance: he slept at the shelter of trees and ate roots, trying to find in nature the path to divinity. He finally reached the city with 40 churches and monasteries. He, like most pilgrims, also went to the monastery of St. Nicholas, where the relics of Saint Simion, a former nobleman who had given up all his wealth, took the path of repentance and mercy.

There, Rasputin met Macarie, a young hermit who was known and liked among the faithful. Although illiterate, he seemed to have grace, preaching the idea that God is there for even the greatest sinners. The church was filled during his sermons, and Rasputin, enchanted above all by the spirit of leadership, chose Macarie to be his mentor. Both he and his neighbors confess that in Verkhoturye, Rasputin found God. He often said that there was always an inner voice urging him to follow the pattern of a Christian’s life and to serve the Lord. “I searched deep in my heart to learn what salvation is. I worked hard and didn’t sleep at all, ”he said later.

Once at home, he gave up alcohol and became a vegetarian, the only vice remaining his tobacco. Here, in his village, Rasputin became the leader he dreamed of. The voice full of drama and theatrical movements made him look like one of those religious fanatics. The phenomenon was not foreign to Czarist Russia. Those ecclesiastical people who carried their beliefs to the extreme and who created an imaginary connection with God, a kind of ancient Greek Pythias, were called “fools in Christ.”

Rasputin knew the amount of madness needed for people to follow him. His confident attitude was as if guided by the words of Antony the Great: “The times will come when people will behave like fools, and if they see someone who does not behave the same, they will rebel against him and say,” You are crazy! ”- because he is not like them”.

A universal Christian

Rasputin was a Christian until his death, devoted to the Russian Orthodox Church. It’s just that he learned from everyone. Russia was blinded by religion, either one of the notoriety of Christianity, or the many more or less dubious sects. And because of this, he was always suspected to belong to one cult or another. He listened to the Baptists, but also to the ancient rite Christians who rejected the reforms of Patriarch Nikon, from 1660 to the spiritists of the Molokans. He also had much to learn from a prisoner — the former Barbarian priest, who had been accused of heresy and imprisoned at the Abalak monastery. Most of all, Rasputin’s past, but also his future, linked him to the cult sect.

Established around 1617, the basic doctrine of the sect was that ordinary people also have miraculous powers. Dressed in white robes, the tribesmen met at midnight in cellars or specially arranged places under the ground, sang religious hymns, and danced wildly, hitting each other with whips, until blood flowed to them. Then they engaged in sexual orgies. Paradoxically, their belief was that only bodily sin brings salvation. The arguments that Rasputin was not part of the clergy were simple: on the one hand, he knew that such obscene behavior would close his way to elitist circles, and on the other, Rasputin was a leader who wanted his followers.

The belief that it has a connection with divinity was strengthened in 1898 when, he says, being on the field, he was shown from heaven the Virgin Mary, pointing to the horizon. Rasputin took this vision as a sign that he had to go on a pilgrimage again. He felt that Saint Mary was preparing for her a great destiny. “Once, I spent the night in a room where the icon of the Virgin Mary was,” Rasputin told many times to those who believed in his powers. When he awoke, tears were shed on the glass of the holy picture, and the saint spoke to him: “I weep for the sins of mankind, Gregory. Go forth, walk, and cleanse the people of sin ”. And as soon as 1900, Rasputin announced that a voice from heaven told him that he should go on a pilgrimage to Mount Athos, Greece.

For a “stranniki” (Russian pilgrim), this whole journey was more than just a journey. It was a struggle with the outside, with the self, because the doubtful world in Dostoevsky’s Demons was on the way. He was always thinking in his mind, raising a wall of defense: “Lord Jesus Christ, have mercy on me, the sinner.” He was fighting a battle like that of Jesus in the wilderness, when in the 40 days the evil temptation enticed him, trying to draw him to his side.

Gregory had his obstacles, which strengthened his faith. “Everything interested me: the good, the bad; I accepted everything and I doubted nothing. I went 40–50 verses a day without observing the storms, the wind or the rain. I rarely allowed myself to eat: in Tambov, I only ate potatoes. I had no money and I didn’t worry about the weather. God has offered. “ This is how the Russian left the house of Christianity.

Six months he went without changing his clothes or washing. It was the day of the sea, and the night was praying. He came to Athos with a desire to become a monk. His opinion changed suddenly, for, according to him, the people of the holy place preferred homosexuality. And although Rasputin was a person who accepted many of the eroticism, which he discovered in Greece, he aroused repulsion towards the monastic life. He returned to Siberia, where before going home he spent at Macarie, his old mentor. “Since you cannot find salvation in a monastery, you must save your soul in the world,” he said, convinced that Rasputin was waiting for a great destiny.

For Griska, it wasn’t good at home either. The villagers looked at him suspiciously, but they had good reason. It seems that on the way to the privilege he had not given up his habits. Once back in Pokrovskoe, he resumed his fugitive idylls with the girls of the place. His sexual passions were impulsive, often creating conflict.

Rasputin explained these beginnings as his dark side, which he embraced as being sent from God. The only one who still supported him and understood that these things were a burden, not a pleasure, was his wife. Rasputin was feeling more and more that his place was no longer in Siberia. Time hastened him — in 1902, he laid his back in the air and started along the Tura and Volga rivers until he reached Kazan.

Rasputin did not accidentally stop in the city of Kazan, because it was then one of the most important theological centers in Russia. But before he got there, his reputation had taken him forward, making room for the souls of people, but also for the unofficial hierarchy of the church. He was a starlet. In the tradition of Russian Orthodoxy, this title was obtained only by that old, wise and graceful priest, who brings to the blessed souls the Blessings, but who also teaches those who have been lost in the path of faith the Decalogue. The Russians needed an iron hand to lead them, but also someone to relieve their thirsty spirit.

The times were not exactly good for the Russian Church: a place as high as the money and involvement in politics made the Russians look for answers elsewhere. The church, a fragile bond between the people and the leadership of the country, stood at the beginning of the twentieth century at the hand of the peasant — he, closest to God, the one who never questioned his judgment. The wisdom of the peasant, that is why the Church needed a shadow. Rasputin knew the game, but he made the rules. He gave the Russians what they wanted. Grigori Rasputin had set himself to conquer the world.

The man who would not die

The Great War had not started well, for the first soldier had fallen. Rasputin. Not a fight on the front. One evening when he was heading home, out of nowhere in the dark, a woman rushed to him and stuck a knife in his stomach. He was about to lose his life, without knowing it was perhaps the first sign that death had already entered the country.

From the hospital bed, Rasputin wrote to the Tsar who had just signed the war against Germany: “I hope for peace and calm, but they are planning a great evil. We who are part of your life know your suffering. It’s very hard not to see each other. Those close to your heart wonder in secret: how can I help you? ”. Although the mysteries of the war were beyond him, Rasputin knew that the imperial family needed him. Former Prime Minister Sergei Witte said the Siberian was a key man: “Rasputin knows Russia better than anyone else: its spirit, state, historical aspirations.” Grigori sent before leaving a special telegram: “Do not let Dad prepare for war, for war means the end of Russia and ours, and he will lose to the last man.”

To begin with, Rasputin was offered a modest apartment in Petrograd. People had found his address and near his door, he was always queuing: they paid as much for a miracle. He could not stay away from the royal family, but also from the scandals.

Arriving in Moscow in March 1915, where the land was located, he stopped at the Yar restaurant, where he and several gypsies spent the morning. Griška began to speak obscenely and suggest that he had an intimate relationship with the landlord. Black with anger, Nicolae received him at the Palace only in June, to give an explanation. A sinful man who fell prey to wine is a childish explanation on such a high level, but Rasputin was forgiven this time too.

Rasputin’s Assassination

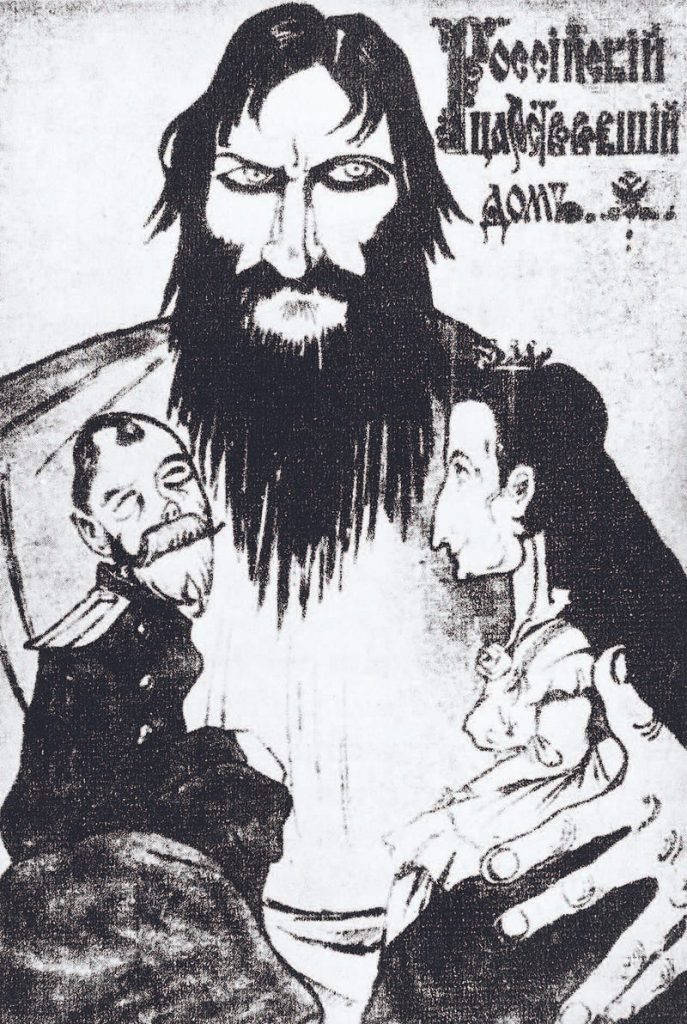

It was December 1916, and the people had been shouting against the Romanovs for some time. Even Rasputin was not forgiven, his name is on the blacklist of people out on the street. The Russian elite also blamed the troika, except that they were aware that the source of the evil was the one who had conquered their society only to destroy it. The most emotionally involved of all was Prince Felix Yusupov.

He was consumed by the fact that no one named ministers as he liked and that the Church had little and was dissolved. Above all, he was pissed that Rasputin would be a German spy. And since no one had the capacity to remove it, there was only one solution: himself. Russia should get rid of its harmful influence, but for this, it needed a well-established plan. It was towards the end of 1916, the snow had settled over Petrograd, and on the streets, it was rumored that Rasputin was to be assassinated.

29 to December 30, 1916. 11 o’clock, close to midnight. Moika Palace. Grand Duke Dmitri Pavlovich, Dr. Stanislaw Lazovert, Vladimir Pureşkevici, with the prince of Russia’s richest family, Yusupov, had prepared for Rasputin a final feast, soaked in arsenic. Josephus sang to them and, song after song, glass after glass, Rasputin had caught himself in the dance of death. The doctor said that one swallow would send him to the other world, but the hours passed, the wine was over, and Griska was still going. Josephus had sealed his fate: he was to die then and there. He pulled out his revolver from behind and, approaching Rasputin, fired. One bullet in his chest was enough for the blood to spill over his blue silk shirt.

His heavy body collapsed on the floor. Yusupov went to the other accomplices to the crime and returned to take the body and get rid of it. When he bent over him, his eyes, with the lens like a snake, hated Felix. Rasputin got up, hindered, and crawled out to where he was screaming: “Felix! Felix! I will tell everything about the land! ”.

Purişkevici took over the command: three shots were fired at Rasputin, one hitting him straight in the forehead. “I killed Griska Rasputin, the enemy of Russia and the Tsar!” They dressed him in the samurai coat and then wrapped him in a light blue drapery. They tied him tightly and threw him into the water of the Neva River. From the frost, he left, and to the frost, he returned. Rasputin was found a few days later, he was mourned and buried, as the most beloved of sinners.

Avid Writer with invaluable knowledge of Humanity!

Upcoming historian with over 30 million views online.

“You make your own life.”