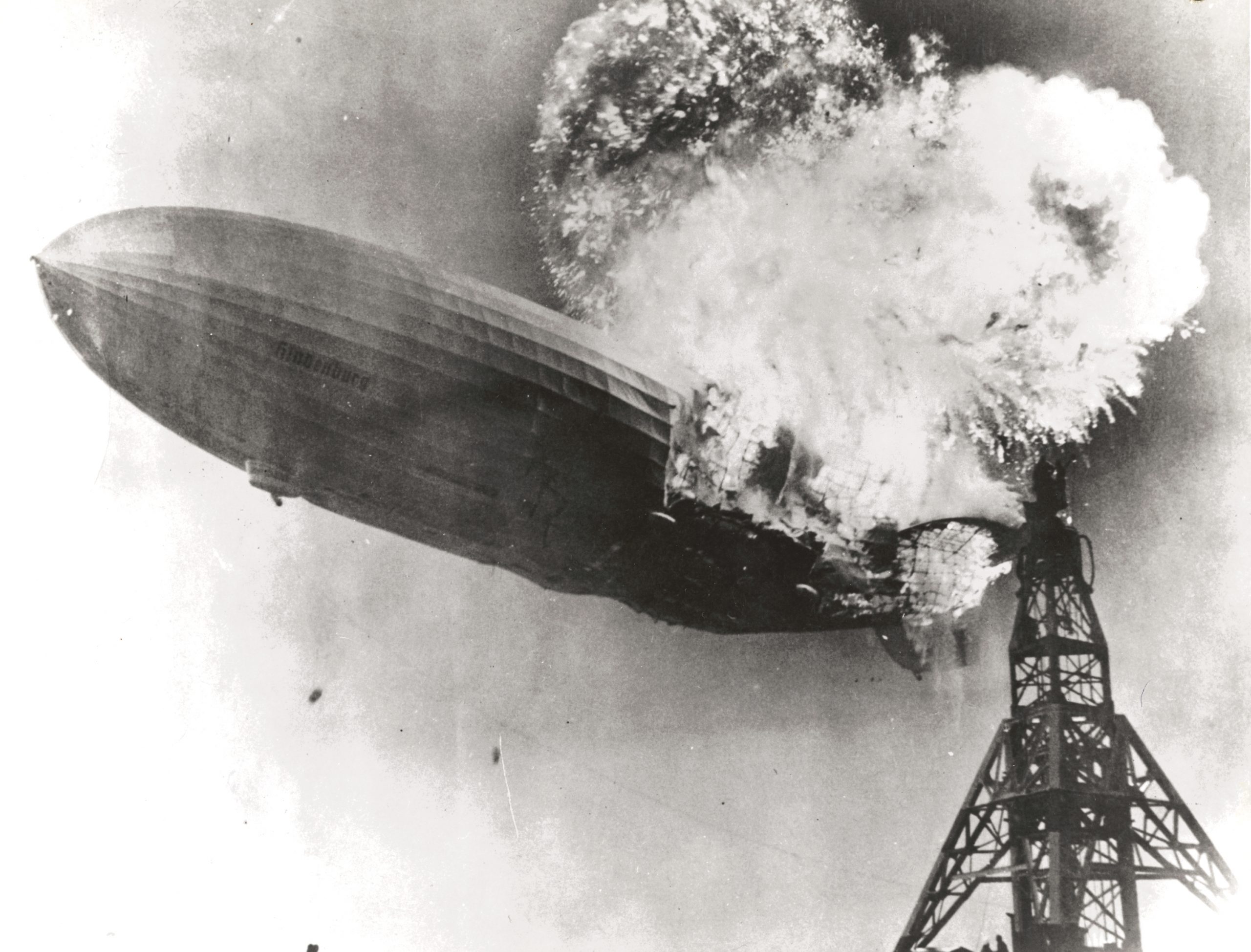

akehurst, May 6, 1937. It’s 7:25 p.m., and Just two minutes away from land, the Hindenburg began the descent operations. The device was only 20 meters from the ground. Suddenly, a flame rose behind it. Then a few explosions were heard, and in a few seconds, the airship turned into a huge torch, which collapsed to the ground.

akehurst, May 6, 1937. It’s 7:25 p.m., and Just two minutes away from land, the Hindenburg began the descent operations. The device was only 20 meters from the ground. Suddenly, a flame rose behind it. Then a few explosions were heard, and in a few seconds, the airship turned into a huge torch, which collapsed to the ground.

The screams of the passengers mingled with the shouts of the crowd present, with the sirens of firefighters and police cars. A thick wave of smoke then enveloped the collapsed case. The cameramen continued to film for 32 seconds of a nightmare, filmed life, in which those present helplessly witnessed the tragic end of the greatest airship ever built.

“Titanic of the Air”

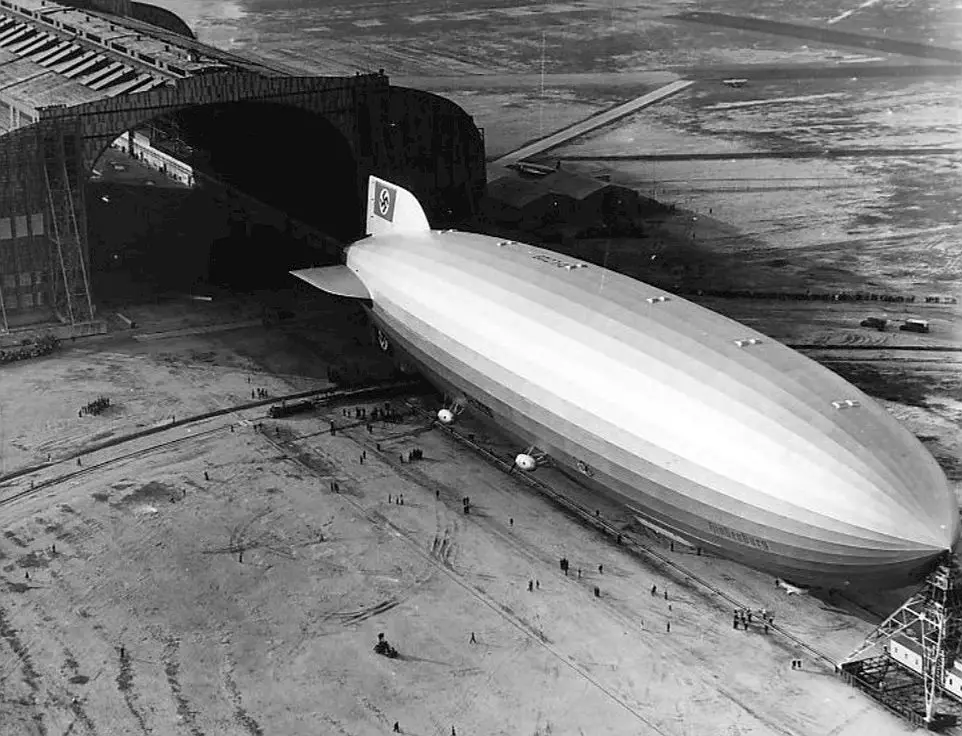

At the end of a real race against the clock, in March 1936, a giant airship, a true leviathan meant to exalt the pride of the Third Reich, came out of the construction site of the Deutsche Zeppelin Reedai after receiving the necessary approvals from Ministry of Air.

It was the largest airship ever built, a true model of perfection, with a length of 245 meters and a height of 41 meters (about the size of a 15-story building). It was equipped with four Daimler-Benz 602 LOF 6 engines, each with 1320 hp. The maximum speed reached was impressive for that time: 130 km / h, and the flight range was 16,000 kilometers!

The Zeppelin LZ129, named after General Hindenburg, was slightly ovoid in shape and had 12 balloons filled with 200,000 mL of hydrogen, so a capacity 10 times higher than the first devices built by Count von Zeppelin. But it was the first time that hydrogen was used instead of helium, a choice that would prove catastrophic.

From some research done by historians, it was found out that Germany (funny enough) ran out of helium. With Hitler’s rise to power, the Americans refused to deliver helium to Germany. But all security measures had been taken. Looking back, we could say that all but one of the security measures had indeed been taken. Otherwise, the Lakehurst disaster would not have taken place.

Traversing the Atlantic in 3 days

After the baptism performed with great pomp by the German authorities, Hindenburg made his first long flight, from Frankfurt, Germany to Rio de Janeiro in Brazil, from October 21–25, 1936. The flight was performed in about 112 hours, covering 11,278 kilometers at a speed average of about 102 km / h.

Throughout 1936, Hindenburg was to provide transportation to Rio de Janeiro (7 round trips) as well as to Lakehurst, USA (10 round trips). Hindenburg’s fastest flight was May 6–7, 1936, between Lakehurst and Frankfurt. The distance of about 6,732 kilometers had been covered in a shower in 61 hours 53 minutes. On May 12, on his return, the distance had been covered in 42 hours and 53 minutes. No liner, no plane, or seaplane had established a similar performance at that time.

The “Titanic of the Air,” as the zeppelin had been called, could thus cross the Atlantic in just three days, compared to the two weeks it took for a ship.

The conditions on board were similar to those on the great luxury overseas ships, but now the zeppelin voyage proved to be the most advantageous alternative for businessmen. They could occupy the cabins on the upper or lower deck. On upper deck A, for example, there were 25 cabins with two bunk beds. Each cabin had a white bakelite sink and a closet that held six men’s suits.

During the winter, the builders took advantage of this period to make various improvements to the airship. Crew cabins, for example, have been reduced to build an additional nine cabins. The new cabins, located on the lower deck B, were now provided with windows, being of course, preferred by very wealthy passengers.

On the upper deck, A, is the dining room measuring 15 meters long and 4.60 m wide. Beyond the plexiglass walls of the dining room is a promenade gallery from where you could look outside. In the center of the hall were four circular tables, each with seven aluminum chairs. Four other smaller tables two were right next to the Plexiglas wall. To the right of the airship is a lounge with an American bar. Next to it was another living room, smaller (5m x 4, 60 m), which served as a reading room. But the pride of this salon was a Bluhner piano, with a tail, made entirely of … aluminum.

On the lower deck was a huge, modern kitchen with a refrigerator and an ice machine, toilets, and a shower room. The smokers also had a small salon of their own, 4, 10x 4, 75, well insulated. Nothing was missing from the board, to make the flight of 55 passengers as pleasant as possible, mostly business people. There was even a small infirmary that had a doctor on duty, and on Sunday, passengers could benefit from a religious service.

The Last Trip

On May 3, 1937, at 7:16 p.m., the Hindenburg airship left Frankfurt for the first of 10 scheduled cross-Atlantic voyages to Lakehurst Air Force Base. There were 36 passengers on board, as well as 61 crew members, with Max Pruss as captain. Ernst Lehmann, the former commander of the LZ 129, was also on board and was to take over in New York, the new position of commercial director of Deutsche Zeppelin Reederei in the big American city.

After 77 hours and 8 minutes of flying, the zeppelin finally arrived 12 hours late at Lakehurst. Down there, relatives, friends, and reporters are waiting for the landing with a lot of emotion. The safety ropes were released, and Hindenburg slid towards the anchor pole. The team next to the anchor pole secured them to the ground. Everyone could see the smiling faces of the passengers, waving their handkerchiefs.

Engineer Groves was under the airship, along with Captain Rosenthal, the commander of the airbase. He is the first to notice a small pale green flame, which begins to play on the gondola of one of the engines. Then everything happened so quickly in just a few seconds, the hull of the aircraft is turned to ashes.

The cameramen on the spot, in order to record the triumphant arrival of the airship, mechanically record the sequences of the catastrophe. The sirens of the police cars, of the firemen, as well as those of the ambulances, could have already been heard. A huge curtain of black smoke from the burning of engine oil covers the airport. As authorities tried to establish a first assessment of the tragedy, special envoys rushed to the nearest telephone booth to transmit the grim news to four points around the globe.

62 of the 97 people on board were rescued (36 passengers and 61 crew members). Most were seriously injured. Captain Ernst Lehmann, who survived the first day of the accident, died the next day. On his deathbed, he murmured barely perceptibly, “Ich kann es nicht verstehen” (I can’t understand). Captain Max Pruss was also rescued, suffering from severe second-degree burns from which he managed to recover.

Meanwhile, Hitler was in Berghof for a few days to celebrate his 48th birthday. At 2.30 in the morning, local time, he gave another speech to the guests, recalling the most important points of his career. A subject well known to auditors, which hardly conceals boredom. A brief call from the Deutsche Nachrichtenburo and Hitler’s Directorate took note of the contents of the radio program, which announced the disaster. He was extremely outraged that all the anonymous letters regarding possible sabotage of the Hindenburg zeppelin were not taken seriously.

Accident or Sabotage?

The immediate order is that no other airship will leave German territory until this accident is clarified. On the morning of May 7, the newspapers had a black border. A commission is sent from the Reich to participate in the investigation. Hugo Eckener, the director of Zeppelin, was also part of the commission. Upon leaving Aspern Airport, he stated that he believed in the version of sabotage. American newspapers published contradictory details, and Captain Prus and Commander Charles Rosenthal were far from sharing the same view on the origin of the accident.

The official investigation attributed the disaster to a static discharge, but the real cause of the catastrophe remains a mystery today. Michael M. Mooney’s book, published in 1972 and entitled Hindenburg, is about an alleged perpetrator of the attack, Erich Spehl, a crew member, a convinced anti-Nazi, who had placed a time bomb on the airship. However, there is no proof to justify these allegations.

Avid Writer with invaluable knowledge of Humanity!

Upcoming historian with over 30 million views online.

“You make your own life.”