the beginning of the American Revolutionary War unfolded, it became clear that the American insurgents could not match the superior British army with sheer force. To keep the flame of the revolution alive, the patriots needed small victories to galvanize neutral colonists for support, but true military victories were difficult to attain with a sustained population of loyalists and agnostic colonists, and the increasingly totalitarian British response. Instead, the American revolutionaries benefited from triumphs that were not as much physical but psychological. This is the story of how superior propaganda and a tragic story led to a strengthened resistance among the colonists as well as perpetuated a continuous theme of antagonism towards a group of people.

the beginning of the American Revolutionary War unfolded, it became clear that the American insurgents could not match the superior British army with sheer force. To keep the flame of the revolution alive, the patriots needed small victories to galvanize neutral colonists for support, but true military victories were difficult to attain with a sustained population of loyalists and agnostic colonists, and the increasingly totalitarian British response. Instead, the American revolutionaries benefited from triumphs that were not as much physical but psychological. This is the story of how superior propaganda and a tragic story led to a strengthened resistance among the colonists as well as perpetuated a continuous theme of antagonism towards a group of people.

The British Strategy

By the summer of 1777, the group of colonial separatists were beginning to pose a significant headache to the British Empire. What would be known as the American Revolutionary War was entering its third year, and though Patriot morale had been increased by small victories in battles at Trenton and Princeton, overall support for the revolution was largely lukewarm with many Americans still uncommitted.

In the Northern Colonies, the British agreed upon a strategy in which Generals Howe and Burgoyne would bulldoze through the colonies from two directions. Burgoyne would descend from Lake Chaplain in Quebec and Howe would advance north from the mouth of the Hudson River in New York. They were to be aided by a third movement that went east from Lake Ontario by officer Barry St. Leger. All three officers were to converge onto Albany and capture the city. This strategy was put in place to sever the patriotic New England Colonies from the rest of the revolutionary movement. Once this was completed, the then commander and chief of the British Army Sir William Howe would then take the rest of his army to Philadelphia to battle with the bulk of the Patriot forces. The plan seemed appropriate, however just weeks after agreeing upon the plan General Howe had decided on a new plan. Instead of linking up first with Burgoyne, he made conquering Philadelphia the primary objective of his 1777 campaign and would He believed Washington’s retreating army was in a very vulnerable position that he had to capitalize on. This left Burgoyne on his own for the British northern offensive.

Through the summer of 1777, the flamboyant Burgoyne descended from Lake Champlain in Quebec with an army of 8,000 soldiers easily capturing Fort Ticonderoga, granting safe portage access from Lake Champlain. Eventually the army disembarked from their ships, needing to portage through thick forest in Upstate New York. Although only 30 miles to separate Lake Champlain from the Hudson River, the terrain proved to be cumbersome in its dense forestry and the sweltering summer heat. Even with the aid of Iroquois scouts, Burgoyne’s army consumed much time, and provisions in the upstate wilderness.

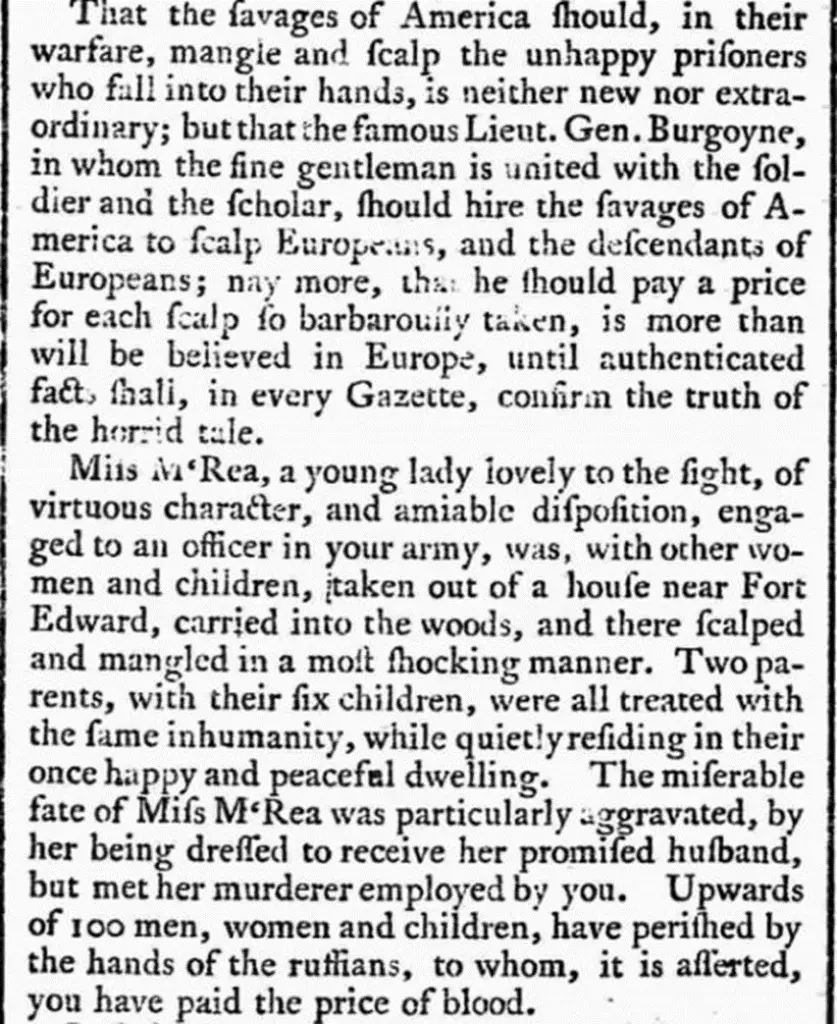

On June 23, 1777, Burgoyne issued a proclamation demanding colonists side with the British or face the wrath of his Native American allies. It was meant to deter any revolutionary sentiment and bolster loyalist support. Native Americans were promised compensation for the capture of colonists, however scalping was condemned unless against “fair opposition”. The proclamation was bombastic and garnered ridicule from many colonial newsletters.

The Tragedy

As Burgoyne continued his march towards Albany, a young woman was making her way up north to Fort Ticonderoga. Hoping to rejoin with her recently engaged fiancé who served under Burgoyne, Jane McCrea embarked on her journey. As McCrae travelled north, she lodged at her fellow loyalist friend Sara McNeil’s home at Fort Edward. Fort Edward had been held by the Continental Army , but was abandoned when it became known that the British were marching down. The Continental Army retreated south to Saratoga, leaving settlers to fend for themselves. The British as in much of their Campaign, had used Iroquois scouts to traverse the land, these scouts however began conducting raids along the settlements of Fort Edwards, one of which would lead to the end of Jane McCrea’s life.

On July 27th 1777, McCrae and McNeil were captured by a band of Wyandot Indians. McNeil was escorted to Burgoyne’s encampment, it was then that she identified McCrae’s scalp carried by a Native American. The news of McCrae’s death spread and mistrust for the Native Americans grew in the British camp as Burgoyne struggled to uncover the truth behind the incident. Initially Burgoyne demanded the perpetrator come forth to be executed, but no Natives came forth. Burgoyne was further convinced to not proceed with his inquest, for fear that it may lead to an exodus of Native American allies. However, the fracturing of Native American and British relations had already worsened from the incident and in the coming weeks many Native Americans deserted the British.

What truly happened to Jane McCrea has been contested. It was claimed that two Native Americans killed her when arguing who would receive the reward. On the contrary it was argued that McCrae was accidentally shot by Revolutionaries and only scalped after she had already been dead. Proponents to this theory attest that her body when found demonstrated only bullet wounds. Either way what truly happened did not matter, because the American revolutionaries knew what story to tell when they caught word of the incident.

The Effects

Although Indian raids were not uncommon for colonists who lived inland, McCrae’s death caused a significant and unique furor among settlers. McCrae was the embodiment of white naivety and innocence. Chaste and pure, contrasted with the barbarous and dark skinned Native Americans. Depictions of her death further accented this contrast, claiming that she had been blonde and killed in her wedding dress while in reality her hair had been brown and she was killed in regular clothes. The Native Americans were decried as scalp hunting mercenaries, and tales reported that McCrae’s scalp was sold to British officers. Stories embellishing her death and its circumstances proliferated in newspapers and taverns. Horatio Gates, the Continental General who had taken over command of the American resistance to the Saratoga Campaign caught word of the incident just as many others had. He further exchanged letters with Brugyone regarding the incident. His letter which abhorred the incident was widely published for colonists to see. Now even neutral settlers felt compelled to fight against the encroaching British Army.

Following the incident, the British went on to mount significant losses in the Saratoga Campaign as resistance continued to mount on the British until a colonial force of armed farmers and militiamen numbered at 15,000 surrounded the British position. They were 50 km from Albany. After major battles of Saratoga, Burgoyne surrendered his army of 7000 men on October 17. This was the largest American victory yet, and prompted France to publically support the American Revolution.

Though a small event in itself, the atrocity propaganda that enveloped McCrae’s death marked a turning point in the revolution that saw neutral settlers mobilized to the revolutionary cause. Revolutionary propaganda, was very sophisticated and entrenched in colonial infrastructure, with the majority of colonial newsletters being sympathetic to patriot causes. American hostilities between the Iroquois and other tribes allied with the British would continue throughout the Revolution. The Native Americans, treated as a monolith of the antithesis of the cultured European man would suffer as the now Americans began to govern their new country. Depictions of McCrae’s death become more and more widespread in the 19th century, in tandem with manifest destiny and Westward expansion. McCrae’s death now was not used as a call against the British but as a cause to legitimate the persecution of Native Americans and uphold the new American ethos.

Christian Nelson is a writer published on various publications on Medium. Having lived in many different countries and experienced many different cultures, Christian hopes to use history as a tool in unearthing similarities from the past and the present while shedding light on forgotten events of the past.