or soldiers in a conflict zone, every drive holds the possibility of terror. Traveling down a road, every thicket of trees can hide an ambush and culvert an IED. The sense of danger and vulnerability only ratchets up for supply and logistic soldiers as they crawl down highways in unarmored trucks. Recent images from Ukraine have shown Russian trucks carrying a variety of homebrew protective solutions. Anything to ease the vulnerability when surrounded by a populace that wants you gone. As strange it is to see trucks covered in logs and other common materials, the practice of crews supplementing vehicles’ armor protection with anything they can find has a tradition as long as armored vehicles.

or soldiers in a conflict zone, every drive holds the possibility of terror. Traveling down a road, every thicket of trees can hide an ambush and culvert an IED. The sense of danger and vulnerability only ratchets up for supply and logistic soldiers as they crawl down highways in unarmored trucks. Recent images from Ukraine have shown Russian trucks carrying a variety of homebrew protective solutions. Anything to ease the vulnerability when surrounded by a populace that wants you gone. As strange it is to see trucks covered in logs and other common materials, the practice of crews supplementing vehicles’ armor protection with anything they can find has a tradition as long as armored vehicles.

The Background

Ad hoc, or appliqué, armor is any protective item attached to a vehicle that it was not originally designed with. The quality of appliqué armor can vary wildly from factory-designed solutions to haphazardly attached logs and everything in between. Likewise, protection levels can range from excellent to purely psychological. Some are even detrimental. The battlefield improvisations are often the most interesting. Partially because they can be so extreme, but also because these modifications are often a physical embodiment of the stress soldiers feel and their will to survive.

This drive to survive has motivated humans for as long as there has been conflict. And as long as vehicles have been used in conflict, owners of those vehicles have been finding creative solutions to improve them. In this sense, improvised armor is a classic piece of military history. From chariots to ships-of-the-line, the possibilities of modifications were limited only by the imaginations of the operators.

The American Civil War is where mechanized vehicles and this type of armor began appearing in a modern sense. It could be argued that the CSS Virginia was the ultimate early example of ad hoc armor. In a rush to build an ironclad, the Confederates affixed an iron shell onto the hull of the scuttled USS Merrimack.

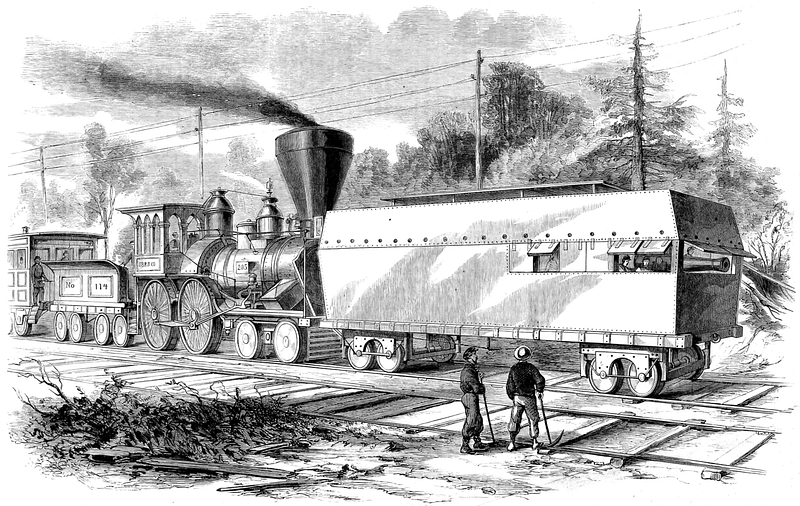

For ground combat, the modern birthplace was possibly at the Baldwin Locomotive Works in Philadelphia. In 1861 a Northern turncoat began destroying parts of the Philadelphia, Wilmington and Baltimore Railroad line. After the saboteur had done his damage, Confederate Snipers prevented Union railroad men from repairing the track. A local inventor named Rufus Wilder designed an armored carriage to protect the workers and subsequently convinced the railroad to buy it and Baldwin Locomotive Works to build it. The monster that emerged was a heavily modified baggage carriage wielding thick armor, a 24 pounder howitzer, and 50 ports for riflemen.

Twentieth-century

It was the British who took this armor off the rails and into the twentieth century. In 1900 Lord Roberts, fed up with the vulnerability of railroads in the Second Boer War, ordered six steam traction engines fitted with armor to begin towing supply trains to his soldiers. These modified tractors were the first true self-propelled armored vehicles.

While the Americans and British started the trend of bolting armor to anything that moved, the Belgians brought appliqué armor into a world war. Prior to World War I, Belgium had a strong road network. This, connected with the flat nature of the country, made it ideal for early automobiles and the Belgians had already taken to using civilian cars with machine guns for patrols. When World War I broke out, a Belgian lieutenant brought back two captured German cars to have armor plates fitted. Belgium used these and a number of locally built Minerva touring cars fitted with armor plates to great effect early in the war and on the Eastern Front.

So successful were the Belgians, that the British took notice. They too started the war with standard civilian vehicles. The first of these were driven by Royal Naval Air Service officers. It was the job of these officers to follow aircraft and recover the aircrews if they crashed. The commander of the section had his personal vehicles armored after a firefight with a German car on one mission. Having seen the promise from the RNAS armored car section and the Belgians, the British created the Royal Naval Armoured Car Division. Using more purpose-built vehicles, armored cars served well through WWI. They were especially important on the mobile Eastern Front and their impact echoed through history. The most notable, spiritual successors to those early modified cars are the notorious gun trucks of Vietnam.

These trucks were the product of continuous Viet Cong and North Vietnamese Army strikes on supply convoys. Suffering high casualties, American crews took it upon themselves to modify certain trucks in the column to fight back. Using whatever materials and guns they could find, Americans modified their vehicles for protection and firepower in the spirit of their Belgian and British precursors.

In World War II, tanks took over as the primary armored vehicles and the nature of ad hoc armor changed. Previous improvised designs had some factory support, but during the war, weapon technology was progressing by leaps and bounds and the complex vehicles were more difficult to modify. Here we see the rise of crew applied field modifications. Desperate to find protection from increasingly more powerful weapons, crews of all nations sought solace in what they could find. With side armor vulnerable to Soviet anti-tank rifles, Germans began adding skirts to their vehicles known as schurzën. The Soviets, suffering from German Panzerfausts, experimented with welding bedframes onto tanks to detonate the warheads away from the hulls. The British Home Guard, short on steel and in need of vehicles for airbase defense, conjured up a notable historic oddity in the form of concrete armored lorries known as Bison.

For M4 Sherman crews, a deep feeling of inferiority drove them to improvise armor in a myriad of ways. Track links secured to the hulls are most commonly seen in photographs, but crews used sandbags, logs, and welded on plates. Some even experimented with concrete — anything to help against German high-velocity guns.

Unfortunately for many of these crews, these additions had limited effect or were detrimental. Tanks of the era relied on angled armor to increase the effective thickness of their armor plating. For example, early war Sherman frontal armor was 51mm (2in) thick and sloped at 56 degrees. So a head-on shot traveling parallel to the ground would encounter approximately 90mm (3.5in) of armor. Contrast that to the Tiger which had 100mm (3.9in) of frontal armor oriented straight up and down. If that same shell were to strike the Tiger it would still only encounter 100mm of armor. But tank armor is specialized, hardened steel; place softer steel on top of it — say track links — and the softer steel will straighten out the incoming projectile relative to the surface it is striking without appreciably slowing it. This normalization effect can reduce the effectiveness of an armors slope.

This instance aside, World War II commanders had other concerns about all of this improvised armor. Welding onto an armor plate could soften it and render it useless. Furthermore, the added weight of these items increases strain on vehicles’ drivetrains. For these reasons, the German High Command banned all ad hoc armor save the schurzën mounted in an approved manner. Other, minor additions were sometimes allowed for the sake of crew morale. Similarly, General Patton banned sandbags from vehicles in his unit fearing they were slowing his formation down and creating maintenance issues.

The Modern Era

Ad hoc armor in the 21st century has been less focused on stopping tank rounds and more on protecting vehicles from guerilla tactics. In Iraq and Afghanistan coalition forces re-experienced the circumstances that led to the creation of gun trucks in Vietnam. Insurgent fighters preferred to target supply convoys over the combat patrols. And when combat patrols were targeted, RPGs and IEDs proved terribly effective against the lightly protected wheeled vehicles favored by the infantry units.

In a bid to increase protection, defense companies scrambled to create slat armor packages and IED-resistant hulls. Even the M1 Abrams, largely invulnerable to many of the threats, received an urban survivability upgrade. As the engineers worked at home, soldiers and mechanics scavenged for whatever protective items they could find. Once again, steel plates were being welded into locations the designers never intended and soldiers returned to their timeless favorite: the sandbag. While poor at stopping tank rounds, sandbags are useful for slowing bullets, shrapnel, and cushioning some blasts. Later in the war, open turreted vehicles gained roofs as locals kept throwing items into the turrets.

In Ukraine, ad hoc armor is appearing for the very same reasons. Before the fighting had started, Russia began placing metal cages on top of their tanks. These are an attempt to protect from modern top-attack missile systems. They had an idea of what was coming.

But the image of trucks covered in logs is the purest — and saddest — form of ad hoc armor. This is not the considered work of an engineer. This is the work of soldiers desperate to survive in a cruel world. This is the American tanker fearing the German 88 or the young Russian fearing a Ukrainian ambush. The soldiers may be different sides of history, the armor may be ugly and ineffective, but for soldiers whose loved ones may be hundreds or thousands of miles away, every bit of reassurance helps.

Former US Army Armor Officer, MBA, and BA in Military History