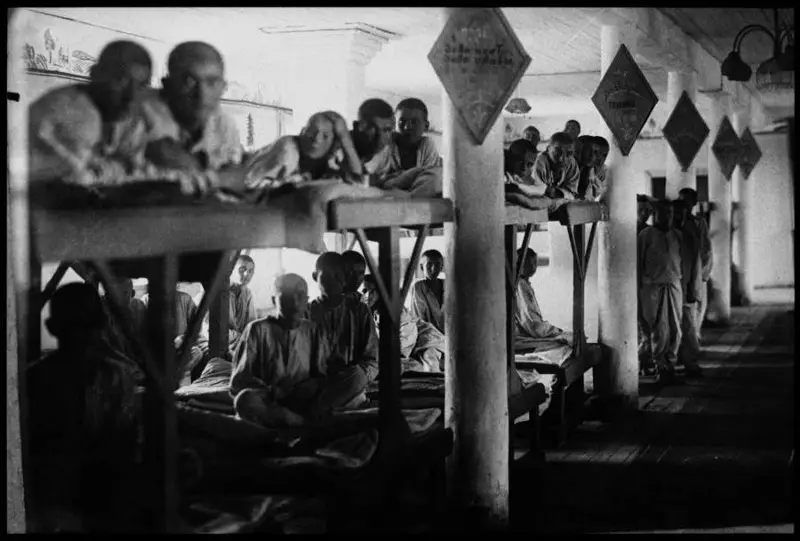

ulags are defined by many people as Russian prisons, but truthfully they were worse than a normal prison. The Gulags were a system of forced labor camps created by Vladimir Lenin right after the First World War. Many historians have actually compared these sorts of prison camps to the concentration camps created by the Nazis in the Second World War. Some argue that the gulag prisons had even worse living conditions and pushed many of its prisoners to death through exhaustion.

ulags are defined by many people as Russian prisons, but truthfully they were worse than a normal prison. The Gulags were a system of forced labor camps created by Vladimir Lenin right after the First World War. Many historians have actually compared these sorts of prison camps to the concentration camps created by the Nazis in the Second World War. Some argue that the gulag prisons had even worse living conditions and pushed many of its prisoners to death through exhaustion.

It wasn’t until Joseph Stalin came to power that the true grim rules within the gulags were set. Most of these rules consist of taking away the human rights of the prisoners. Soviet leaders didn’t like to refer to gulags as prisons, but more as labor camps that are used by various Soviet manufacturers to provide cheap labor with the goal of raising the Russian economy.

However, experts have analyzed how efficient this sort of labor was to reach the conclusion that the labor provided by gulags didn’t raise the Soviet economy by that much, the labour barely reaching 5% of the total Soviet GDP. During 1930 and 1953 (whilst Stalin was in power) over 1.8 million prisoners who were incarcerated died due to various reasons such as diseases, starvation, or exhaustion.

In 2011, Emily Johnson of the University of Oklahoma discovered a series of documents belonging to Latvian poet and journalist Arsenii Formakov (1900–1983). Among them was the private correspondence in the gulag — the letters he sent to his wife.

Formakov’s correspondence from the Gulag

The main source for this article is the book written by Emily Johnson who translated and edited Formakov’s letters. In the book, the book also contains some interesting drawings that are trying to depict not only the state of Formakov’s mental health during his incarceration but also how he tried to keep himself sane from the horrors inside the gulag.

As mentioned before, it is imperative to understand that the letters written by Arsenii Fomrakov did not depict the horrors of the Gulag to their true extent as these letters were meant for his family members, so in order to make them not worry about him, he had to lie quite often about what was really going on in the gulag.

Formakov was convicted in 1940 of anti-Soviet sentiments following the USSR’s invasion of Latvia and was sent to forced labor in Siberia for eight years, where there were already 2.9 million prisoners. Many Romanians were also incarcerated in the gulags of Siberia, especially from Bessarabia and Bucovina.

The letters, scribbled by censors and worn out by the weather, illustrate the hardships detainees went through. These have been translated from Russian into English, giving other readers the opportunity to go through them.

The correspondence also provides details on the double catastrophe of life, both under the Soviet and Nazi regimes, a history that still defines the identity of today’s Latvia. But it is strange how they had the possibility of contacting the outside world soo much. Many sources claim that the gulags of the Stalin era were broken by the rest of society, like alternative marginal worlds where prisoners disappeared without being heard from.

However, some detainees enjoyed, at least in theory, certain privileges. Although the rules varied according to the place of detention and, of course, the prisoner and the seriousness of the “crime”, they could have the privilege of unlimited correspondence. On the other hand, in the case of Formakov, who was a political prisoner, there is a severe limitation of only 2–3 letters per year!

In the first three years of his detention in the Krasnoyarsk region, the poet had no information about his family, as Latvia was under Nazi occupation. Only in 1944 was he able to send letters and did so regularly until 1947, when he was released (early, for good behavior). He was convicted again in 1949 for political reasons. He also continued to send letters home during this period, until his release in 1955.

The daily life of a Gulag Prisoner

The letters Formakov sent described his daily experiences. He talked about the privileges he gained by participating in cultural activities, including access to confectionery and extra rations. He also describes his efforts to take care of his damaged teeth and get new clothes. He talks about the fear of being moved to another place, where work and living conditions are more difficult. The rumors that he heard from other such forced labor camps were terrifying, to say the least. Some prisoners were forced to work for 3 days without any food in the blistering Siberian cold.

Despair is illustrated in other letters. For example, in 1945 he was transferred from an indoor activity where he made sewing machine needles to heavy outdoor work. Here is a small paragraph from one of Farmakov’s letters describing the wish of death due to heavy injuries and exhaustion:

“Now that everything is in the past, I can say that four months last year (from August until I was injured) were physically very difficult for me. Sometimes you pull yourself up to the car with a cross on your shoulder, one that is heavy, damp and has the texture of a log. You’re sweaty, your heartbeat is so strong that you feel like it’s going to jump out of your chest, you’re breathing so hard that you start panting like a horse and you start thinking: let your foot give way. You will fall and cross, it will fall on you and this will be the end: there will be no more suffering and everything will end forever! ”

In another letter, Formakov describes the performances as part of the cultural brigade. In a letter to his wife on March 9, 1946, Formakov described the positive attitudes that detainees were forced to display, contrasting with reality:

“We had a concert on March 8, in honor of International Women’s Day. I was a master of ceremonies. You make a few smart remarks and then go back, you release your soul and you just want to cry… That’s why I hold on to me; my soul is always enclosed in a corset ”.

Along with the standard letters, Formakov also made holiday cards. In other cases, he wrote and illustrated short stories for his two children: Dima, who was five years old when Formakov was first arrested in July 1940, and Zhenia, who was born in December 1940.

Suppressing horrors

Because he knew that the letters sent (even those sent illegally) could be inspected and because he did not want his family to worry, the poet did not describe the true extent of the horrors that gulag survivors recounted. He does not mention beatings, or imprisonment and also omits to mention acts of criminal violence against other weaker detainees, usually political detainees.

However, the letters capture details that rarely appear in other sources. For example, in 1941, he was able to watch the Sun Valley Serenade, an American comedy. In Moscow, a ticket to such a show was extremely expensive. This also refers to rumors that the ruble has devalued significantly.

Such passages support the idea that gulags were more connected to the rest of society than previously thought. Despite this, their number was so high that it is very difficult to describe the true horrors that were going on, taking into consideration that there were over 100 such camps all over the Soviet Union.

Avid Writer with invaluable knowledge of Humanity!

Upcoming historian with over 30 million views online.

“You make your own life.”