ananas, it turns out, have been around for a long time. The first settlers in Papa New Guinea, in the western Pacific, are thought to have arrived as early as 5000 B.C., according to National Geographic. Not long after, these settlers started cultivating bananas. According to The History of the Banana, other nations in the Malay Archipelago — which include Indonesia and the Philippines — were planting bananas around the same time as the people of Papa New Guinea.

ananas, it turns out, have been around for a long time. The first settlers in Papa New Guinea, in the western Pacific, are thought to have arrived as early as 5000 B.C., according to National Geographic. Not long after, these settlers started cultivating bananas. According to The History of the Banana, other nations in the Malay Archipelago — which include Indonesia and the Philippines — were planting bananas around the same time as the people of Papa New Guinea.

Even today, with bananas growing all over the world, scientists are greatly interested in bananas from the small island nation of Papa New Guinea. It turns out that these ancient Papa New Guinea bananas have genes capable of protecting one of the world’s most popular fruits from climate change, pests and disease, according to ABC News Australia.

Bananas have been central to global conflict

And if you know as much about bananas the same as I now do, you can see why the fruit needs some protection. It’s worth knowing that, in the 7,000 years since the Archipelago peoples planted bananas, the fruit has been central to conflicts across the globe.

This should come as no surprise. People like bananas. Soldiers like bananas. Soldiers are people. So, when conquerors of one nation smash another culture, it’s only natural that they would steal their bananas and bring them back home with them.

Take Alexander the Great: He invaded India and then, in 327 B.C., he brought those bananas along with him to Europe

Then, around the 1st century B.C., Muslim Arabs showed up in East Africa with bananas, and used them to purchase slaves, among other things, according to Mashed. Meanwhile, in 650 A.D., Middle Eastern soldiers called the fruit ‘banan,’ which is multiple sources say comes from the Arabic word for ‘finger.’

And then in 1516, Spanish missionaries that wanted to convert the locals to Christianity also wanted to convert them eating bananas, National Geographic says. In the New World, more often than not, slaves were forced to plant and harvest bananas, notes Mashed.

World’s Fair brought bananas to America

And while Spanish settlers aimed to plant bananas in Florida in the early 1600’s, they didn’t have much success. Before the World’s Fair of 1876 — which was held in Philadelphia — most Americans were unfamiliar with bananas, according to TED-Ed. As the Pennsylvania Museum notes, “Wonders and marvels never before witnessed … delighted the consuming audiences” at the World’s Fair in 1876. One of those delights was the banana.

With demand for bananas exploding in America, a firm then known as the Boston Fruit Company began importing them from the West Indies. The Boston Fruit Company aggressively marketed its product across the Eastern corridor of the United States, and shipped them to Boston, Philadelphia, Mobile, New Orleans and New York, reports the New Orleans Historical Collection.

Banana business flourished in Latin America

But Latin America is where the corporation, which would soon be known as the United Fruit Company, would grow exponentially. Starting in the late 1800’s, and continuing into the early 1900’s, the United Fruit Company spread its reach to multiple countries in Central and South America. (the Boston Fruit Company became the United Fruit Company in 1899).

Some years later, the Nobel Prize winning Chilean poet Pablo Neruda memorialized what he thought of the company in a poem simply named “The United Fruit Company.” In it, Neruda wrote: “The Fruit Company, Inc. reserved for itself the most succulent, the central coast of my own land, the delicate waist of America.”

“The Fruit Company, Inc. reserved for itself the most succulent, the central coast of my own land, the delicate waist of America.” — Pablo Neruda, 1970 winner, Nobel Prize in Literature

As Neruda himself notes in his poem, the term ‘Banana Republic’ actually came from United Fruit Company’s expansive reach in Latin America. By 1946, the firm owned one million acres of land in Columbia, Costa Rica, Cuba, Guatemala, Honduras, Jamaica, Nicaragua, Panama, Nicaragua and Venezuela, National Geographic says. United Fruit Company wasn’t shy about getting its nose into local politics. But more about that later.

Likewise, in Gabriel García Márquez’s book One Hundred Years of Solitude, the author writes that when the Banana Company (presumably United Fruit Company ) arrives in the fictional town of Macondo, it brought with it first modernity and then doom. “Endowed with the means that had been reserved for Divine Providence in former times,” García writes, the company “changes the pattern of rains, accelerated the cycle of harvests and moved the river from where it had always been,” a reporter recounts in a commentary piece on the topic in The New York Times.

“Endowed with the means that had been reserved for Divine Providence in former times [the company] changes the pattern of rains, accelerated the cycle of harvests and moved the river from where it had always been.” — Gabriel García Marquez, winner, 1982 Nobel Prize in Literature.

If modifying weather patterns and river flows aren’t enough, that’s not all that United Fruit Company did, as both García and Neruda note in their works.

United Fruit dominated Latin American politics

The United Fruit Company played an oversized role in politics in the Latin American nations where it grew bananas. Visualizing the Americas, a publication of the University of Toronto, notes: “The United Fruit Company consolidated its power through various means: it installed authoritarian civilian and military governments that gave concessions to land, railroads and ports; it divided its labor force along ethnic and racial lines…”

“The United Fruit Company consolidated its power through various means: it installed authoritarian civilian and military governments that gave concessions to land, railroads and ports; it divided its labor force along ethnic and racial lines…” — Visualizing the Americas

The sometimes-corrupt leaders of poor Latin American nations were often more than happy to sell their land to United Fruit Company and give it large tax breaks. According to Country Studies: Honduras: “Companies [in Honduras] gained exemptions from taxes and permission to construct wharves and roads, as well as permission to improve interior waterways and to obtain charters for new railroad construction.

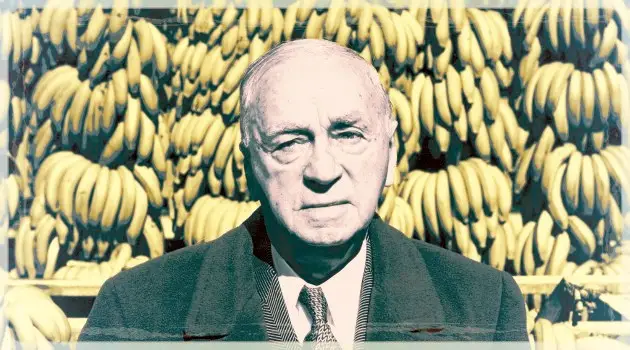

‘Banana Man’ instigated coups in region

The boss of United Fruit Company was one Sam Zemurray, a Russian immigrant who came to New Orleans penniless, when he was 14, but who became wealth by age 21, reports the New York Post, hardly a shining star in the arena of objective and honest journalism. Nevertheless, Sam ‘the banana man,’ as he was sometimes known, figured out how to get bananas to the markets more quickly than his competitors, and bought massive amounts of land in Honduras, among other places in the region.

In 1911 Zemurray proposed a plan to reinstate deposed Honduran president Manuel Bonilla, who was then living in exile in New Orleans. At the time, Honduras owed British banks more than $100 million, and the British were threatening invasion. But the United States and Honduras had reached agreement for the payment of its European debtors.

The problem was, that the United States’ plan would deflate the United Fruit Company’s power and ability to draw low-tax revenue. Zemurray wanted to reach his own agreements on custom taxes with the government of Honduras. With that thought in mind, Zemurray hatched a plan to reinstate Bonilla, according to the United Fruit Historical Society. The crafty plan was successful, and in 1912, Bonilla was successfully reinstated.

Bonilla rewarded Zemurray with land concessions and low taxes, just as the banana man had hoped.

United Fruit Company ran a national post office?

Meanwhile, in 1901, Guatemala hired the United Fruit Company to manage the country’s postal service, and in 1913, the company created the Tropical Radio and Telegraph Company to operate the parent company’s radio network, according to Source Watch.

Just imagine if the United States Government invited Google to manage the U.S. Postal Service or to take over National Public Radio. We wouldn’t think of it. But apparently Guatemala did.

United Fruit Company falls into decline

Zemurray played a leading role in supporting corrupt dictators and toppling democratically elected leaders across Latin America. The businessman retired from United Fruit Company in 1951, and died in 1961. But his company lived on — for a while.

The United Fruit Company declined in influence after Zemurray died, and its activities became known around the world, according to The End of History. One factor that affected the future of the United Fruit Company was Panama disease, a devastating disease of bananas caused by a soil-inhabiting fungus. One method that the firm used to attempt to combat the Panama disease was depositing silt from rivers and swamps from five to seven years, which they hoped would create nutrient-rich soils that would eventually support the re-growth of bananas, while drowning the fungi, according to Gala, a learning platform. The plan didn’t work.

The firm faced other problems too: As Latin American countries began strengthening their labor laws, some of them specifically targeted United Fruit Company, according to Wikiwand, an information curator.

As the demand for bananas decreased in America, due to the availability of processed fruit, United Fruit Company diversified its operations, and eventually merged with AMK Corporation In 1990, the conglomerate changed its name to Chiquita Brands® International.

Firm has new name, but controversies continue

But, like United Fruit Company, Chiquita® has been no stranger to controversy. In 2007, Chiquita® agreed to the U.S. Department of Justice’s demands’ that it pay a $25 million fine — all because it had paid Columbian terrorist groups for protection, a violation of U.S. anti-terrorist financing laws, according to CNN.

Today, Chiquita® distributes about a third of the world’s export banana market, according The Atlantic, indeed making it ‘top banana’ in the industry. But even so, most banana plantations are monocultures, where only one type of crop is grown: At least 97 percent of internationally traded bananas come from one single variety, the Cavendish, according to BananaLink, which works for economically sustainable banana production.

Genetic diversity key to banana sustainability

Which brings me back to the scientists who are studying the genes of bananas in Papa New Guinea. Genetic diversity is key to protecting bananas such as Cavendish from the adverse effects of climate change, pests and diseases, according to Sebastien Carpentier, a Belgium-based scientist, who led a an expedition to Papa New Guinea to study its bananas, ABC News Australia reported in 2020.

So, as you eat that banana that you’re holding as you’re reading this article, you now understand why protecting the rainforests in a country that is more than 9,000 miles away from you is important to both your livelihood, and to the livelihood of the fruit in your hand that, many years ago, Arabs called ‘banan,’ because its shape reminded them of the word for finger in in their own language.

When I was a kid, my mom thought that I’d have my own talk show because I was always asking people lots of questions about themselves. When I graduated college, I began living my own dream as a reporter for a news media outlet. As a journalist, I spoke daily with public affairs officers who represented diverse government and corporate clients.

I soon realized that public affairs combined the best of both worlds of journalism and television talk shows — I get to learn interesting and unusual things about people who worked with me, I then get to tell their story. With this thought in mind, I spent two years at CIA, where I was a supervisor in the Public Communications Branch at the Office of Public Affairs.

As a strategic communicator, I juggle many balls — but I’m a writer first. Writing is my first love. You can say that I’m addicted to it.

On a personal level, my parents taught me the value of travel when I was young, and since then, I’ve been an avid traveler — I have visited 20 countries. Though I’ve learned important lessons from each of my trips, my trip to Chile — the string bean-shaped country — was my favorite.

To learn more about me and my digital travels, visit my Twitter page.