ivorce is a nasty business, especially if you’re a 17th-century peasant. They’re lengthy, incredibly expensive, and generally unpleasant for everyone involved; that’s why lower-class Britons who were trapped in an unhappy marriage figured out a semi-legal way to make everything easier.

ivorce is a nasty business, especially if you’re a 17th-century peasant. They’re lengthy, incredibly expensive, and generally unpleasant for everyone involved; that’s why lower-class Britons who were trapped in an unhappy marriage figured out a semi-legal way to make everything easier.

Let’s say you and the missus haven’t gotten along for some time. She is having an affair with another fellow, and she’d rather go and live with her new beau — except, of course, she can’t do that without exposing him to the accusation of ‘criminal conversation’, aka ‘stealing one man’s wife’ (something that could land him in jail.)

You, on the other hand, are sick and tired of providing for that hussy and paying her debts — as is your duty as a husband. Maybe you are having a little fling with the baker’s daughter, too.

What shall you do?

Spouse on a leash

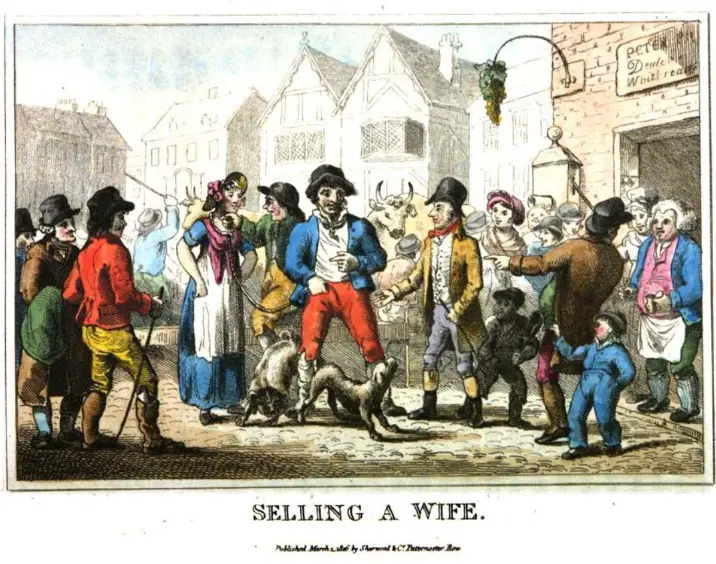

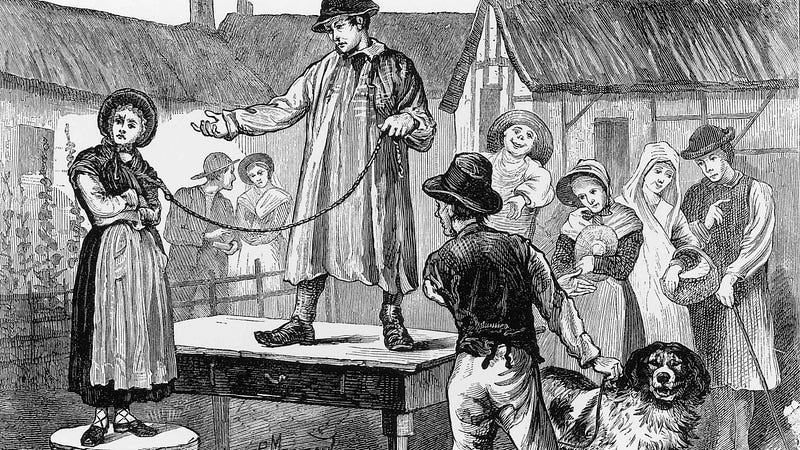

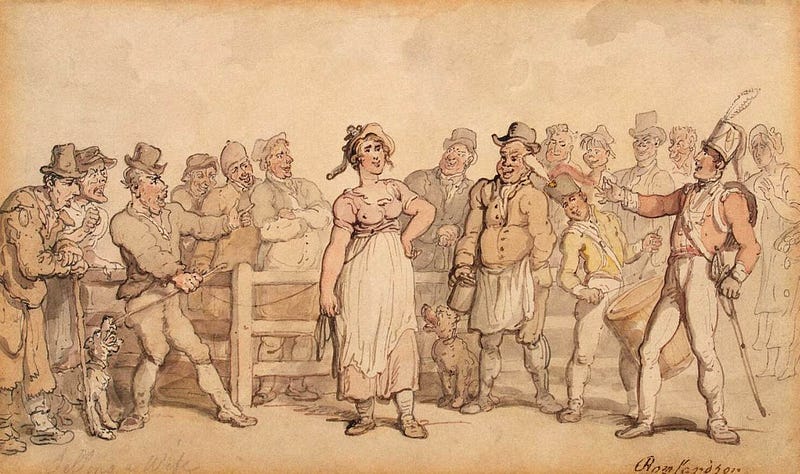

Well, no need to involve a court when you could just tie a halter (or a pretty silk ribbon, if you fancied it) around your wife’s neck (or her wrist, or her waist) lead her to the marketplace, and parade her around.

You could fasten the other end of the rope to the post generally used for cattle — given that the sales took on the form of cattle auctions, and the toll for a beast sale often had to be paid to the market officials.

When you were sure to have everyone’s attention, you could start declaring your spouse’s virtues (including — but not limited to — her weight and the condition of her teeth) to the onlookers and auction her off to the highest bidder.

The halter was central to the ritual: it had to be new, and it was usually made of rope, but halters made of silk or decorated with ribbon were popular, too.

Delivery in a halter symbolized the surrender of the wife into another man’s possession, and it was an essential part of a correct, “lawful” sale.

Sometimes the woman would tie the leash around her waist, under her clothes, and kept the rope in her pocket so it was not visible: but, at the beginning of the auction, she had to give the other end to her husband.

Everyone (kinda) goes home happy

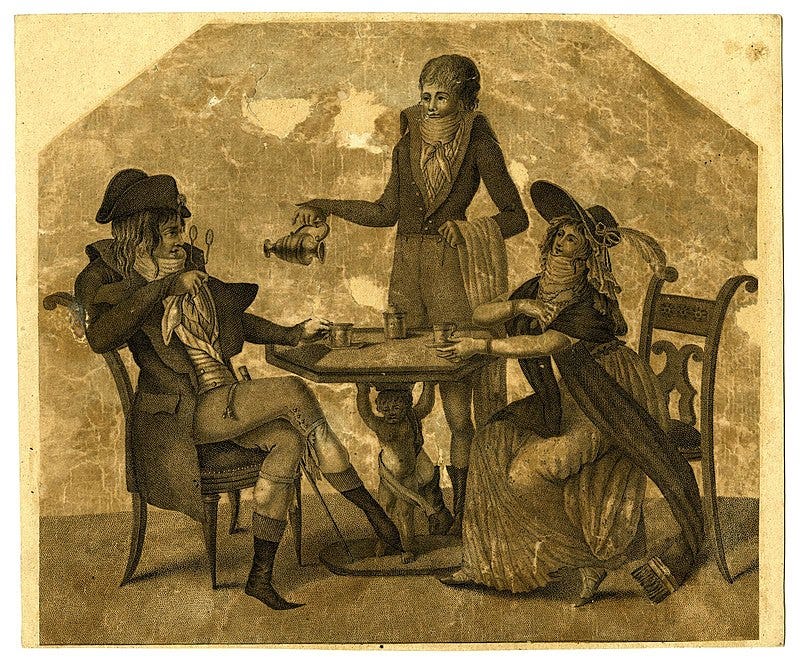

Treating your spouse like a farm animal in front of the whole town may sound like a cruel, humiliating practice, but it wasn’t always the case: there was usually just one bidder — the woman’s new love interest— chosen long before the auction was supposed to take place, and the wife had to agree to the sale. She had the right to refuse to be sold if the winning bidder was not to her liking, and there are also a few recorded instances where the woman ended up buying herself.

In most cases, it seems that the wife went along happily with the whole business, and it was fairly common for her, her new partner, and her old one to sit down for a pint of beer and a good laugh after the auction.

The Happiest Day Of My Life!

A toll book records that, in 1773, a fellow named Samuel Whitehouse decided to sell his wife Mary to another gentleman: the book stated the price and offered a side note stating that all the parties went home “exceedingly well pleased” with the deal.

A man named Moses Maggs sold his wife for six shillings and three gallons of ale: the young woman smiled cheerfully and her new husband planted a loud kiss on her rounded cheek by way of ratification, while another woman declared being sold at Smithfield market had been “the happiest moment of her life”.

Another case records a woman who was led all around the market three times by her new husband, with hundreds of people following her: she smiled and waved a blue handkerchief at her public like she was a Hollywood celebrity.

Sometimes an impromptu wedding was also thrown on the spot: in 1797 a woman was sold for two shillings and a six-pence to a man she had an affair with, and “the marriage service was afterward read by a merry [auctioneer] who received half a guinea for his trouble.”

It’s legal, innit?

Despite British law clearly stating that selling one’s wife was positively, unquestionably, 100% illegal, people kept doing it and attempted to legitimize it with a series of made-up (but pretty interesting) rules.

A bill of sale was often written between the parties, for example, and a certain amount of formality was observed. Publicity was key: the bargain had to take place in the marketplace or some other place of trade (like an inn). The wife had to loudly state her consent, and the auction was often preceded by a public announcement. Sometimes witnesses were required to sign the contract.

Wife sales were a big show and attracted hundreds, and sometimes thousands, of attendees.

The custom was frowned upon in polite society, but not much was done to stop it — quite the opposite: one early 19th-century magistrate stated he did not believe he had the right to prevent wife sales, and there were some cases of local Poor Law Commissioners forcing husbands to sell their wives, rather than having to maintain the family in workhouses.

It also needs to be said that it was pretty damn hard to prove two people were married — given that, until 1753, it wasn’t essential for a marriage to be recorded in any register or to be performed by a clergyman; so-called “common law” marriages were widespread: if a couple lived together for some time and referred to themselves as “married”, they were, without ever going through a formal ceremony.

How Much For That One?

Prices varied greatly: in 1865 a man supposedly sold his wife to an American sailor for 100 pounds, plus 25 pounds each for her two children – a real bargain. On the other hand of the spectrum, a woman was once sold for the not-so-great figure of three-farthings.

But it was not at all uncommon for wives to be also sold for a glass of beer, a bowl of punch, or some tobacco. A donkey driver sold his wife for thirteen shillings and a donkey. In 1832, a farmer famously sold his wife for twenty shillings and a Newfoundland dog, that he brought home using the same halter he had brought his wife to the market with.

In March 1808 a man sold his wife to a fisherman, in the market at Brighton, for twenty shillings and a blunderbuss.

Sometimes people got a bit carried away: in 1833 a “dashingly attired” woman was put on sale in Bath… but she had already been sold earlier the same week at Lansdown Fair.

Another husband had second thoughts during the auction and tried to get out of the business, but his wife (a tough cookie named Mattie) slapped him with her apron and said, “Let be yer rogue. I wull be sold. I wants a change!”

Not-So-Distant Past

As much as the concept of wife-selling may sound like it could only belong in a very distant, very uncivilized past, this outlandish practice continued up into the early 20th century: records exist of a woman in Leeds who was sold to one of her husband’s workmates for £1 as recently as 1913!

To put it into perspective, the Wright brothers made their first flight in 1903. Cars were a thing. People went to the cinema.

The custom seems to have originated around the end of the 17th century, but there is evidence of similar events dating back to 1302; they became so popular to be featured in a novel (Thomas Hardy’s 1866 The Mayor of Casterbridge) and even inspire a few popular songs (this one and this one, for example).

30-something, born and bred in Italy. If you leave me unattended in your house I will sand down and repaint every piece of furniture you own. Can’t parallel park to save my life.