ay 10, 1940. In the early hours of the day, Hitler launched the invasion of Belgium, Luxembourg, and the Netherlands. These three countries had two similarities. On the one hand, they were officially neutral; on the other, they couldn’t count on a well-equipped army. Luxembourg, for instance, was conquered in less than twenty-four hours. When the Wehrmacht crossed their borders, their fate had already been sealed. In this scenario, what frightened Germany’s foes the most was the Führer’s clear intention to move towards Paris. If France had capitulated, Hitler would have succeeded in controlling nearly all continental Europe (either directly, by means of puppet governments, or through political alliances).

ay 10, 1940. In the early hours of the day, Hitler launched the invasion of Belgium, Luxembourg, and the Netherlands. These three countries had two similarities. On the one hand, they were officially neutral; on the other, they couldn’t count on a well-equipped army. Luxembourg, for instance, was conquered in less than twenty-four hours. When the Wehrmacht crossed their borders, their fate had already been sealed. In this scenario, what frightened Germany’s foes the most was the Führer’s clear intention to move towards Paris. If France had capitulated, Hitler would have succeeded in controlling nearly all continental Europe (either directly, by means of puppet governments, or through political alliances).

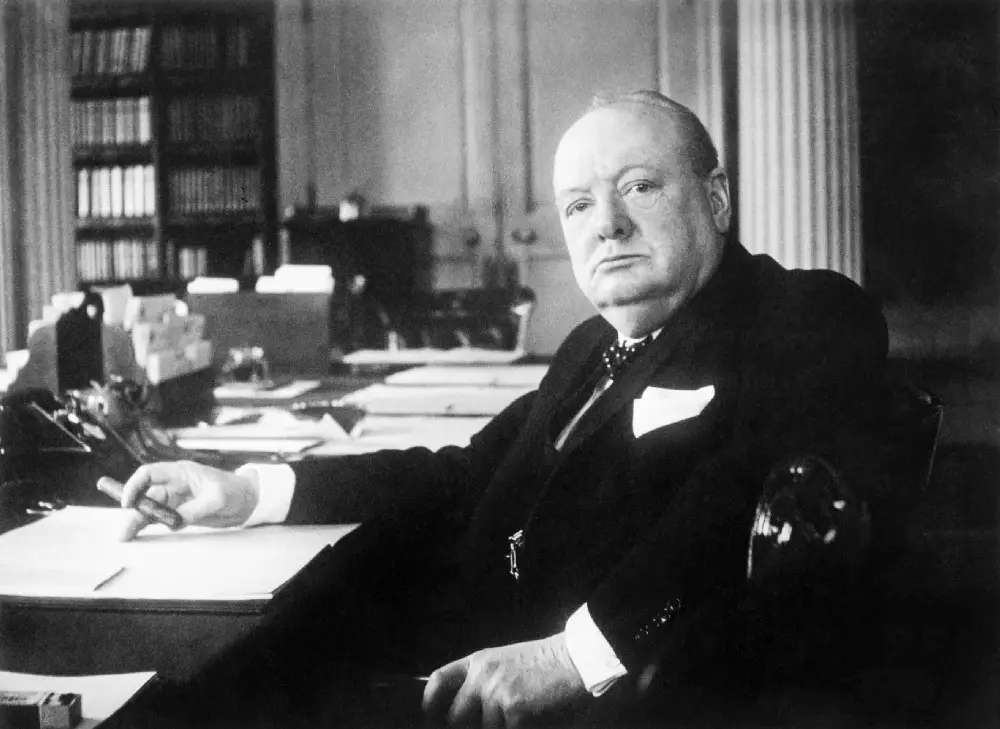

In England, Winston Churchill was about to replace Neville Chamberlain as Prime Minister. Chamberlain had been blamed for his foreign policy of appeasement, and both the Labour and some sectors of the Conservative Party were asking for a deep change. Churchill embodied that change. He stepped in Buckingham Palace as an unpopular politician, even within his party, and stepped out of it by “walking with destiny”.

Blood, Toil, Tears and Sweat

May 13, 1940. Even though the Battle of France had already started a few days before, that Monday Hitler’s panzer corps broke through at Sedan, a French outpost located near the Ardennes. Thanks to this, the Wehrmacht was able to begin its penetration within France territory.

In London, Churchill was about to deliver his first speech as Prime Minister, by which he was also asking the House of Commons to declare its confidence in his Government. This first speech was delivered in a tough situation, as the majority of Conservative members of the Parliament did not believe Churchill to be the right person for that role.

Churchill began his speech by asking the entire Parliament’s confidence in his Government, from both Labour and Conservative. Then. he talked about the War Cabinet he had just formed to face the oncoming conflict against Germany. Hence, he described what his policy would have looked like, thus getting England ready for the hardest challenge of its History.

Sir, to form an Administration of this scale and complexity is a serious undertaking in itself, but it must be remembered that we are in the preliminary stage of one of the greatest battles in History, that we are in action at many points in Norway and in Holland, that we have to be prepared in the Mediterranean, that the air battle is continuous and that many preparations have to be made here at home. In this crisis I hope I may be pardoned if I do not address the House at any length today. I hope that any of my friends and colleagues, or former colleagues, who are affected by the political reconstruction, will make all allowances for any lack of ceremony with which it has been necessary to act. I would say to the House, as I said to those who have joined the government: “I have nothing to offer but blood, toil, tears and sweat.”

We have before us an ordeal of the most grievous kind. We have before us many, many long months of struggle and of suffering. You ask, what is our policy? I will say: It is to wage war, by sea, land and air, with all our might and with all the strength that God can give us; to wage war against a monstrous tyranny, never surpassed in the dark and lamentable catalogue of human crime. That is our policy. You ask, what is our aim? I can answer in one word: victory. Victory at all costs, victory in spite of all terror, victory, however long and hard the road may be; for without victory, there is no survival. Let that be realized; no survival for the British Empire, no survival for all that the British Empire has stood for, no survival for the urge and impulse of the ages, that mankind will move forward towards its goal.

We Shall Fight on the Beaches

June 4, 1940. The Battle of Britain had not started yet, but the United Kingdom had already witnessed the cruelty of that new Great War. During the French campaign, the British Expeditionary Force lost some 68,000 soldiers. Nonetheless, Churchill had succeeded in rescuing more than 330,000 soldiers from Dunkirk’s beaches. The Operation was called Dynamo, but it became known also as the Miracle of Dunkirk.

Churchill delivered a second speech to the House of Commons the day in which the last Allied troops were evacuated from France. Despite the relief, what the Prime Minister had to talk about was a military disaster. However, he still believed that Hitler could be won.

The enemy attacked on all sides with great strength and fierceness, and their main power, the power of their far more numerous air force, was thrown into the battle or else concentrated upon Dunkirk and the beaches. Pressing in upon the narrow exit, both from the east and from the west, the enemy began to fire with cannon upon the beaches by which alone the shipping could approach or depart. They sowed magnetic mines in the channels and seas; they sent repeated waves of hostile aircraft, sometimes more than 100 strong in one formation, to cast their bombs upon the single pier that remained, and upon the sand dunes upon which the troops had their eyes for shelter. Their U-boats, one of which was sunk, and their motor launches took their toll of the vast traffic which now began. For four or five days an intense struggle reigned. All their armoured divisions — or what was left of them — together with great masses of German infantry and artillery, hurled themselves in vain upon the ever-narrowing, ever-contracting appendix within which the British and French Armies fought.

Meanwhile, the Royal Navy, with the willing help of countless merchant seamen, strained every nerve to embark the British and Allied troops. Two hundred and twenty light warships and 650 other vessels were engaged. They had to operate upon the difficult coast, often in adverse weather, under an almost ceaseless hail of bombs and an increasing concentration of artillery fire. Nor were the seas, as I have said, themselves free from mines and torpedoes. It was in conditions such as these that our men carried on, with little or no rest, for days and nights on end, making trip after trip across the dangerous waters, bringing with them always men whom they had rescued. The numbers they have brought back are the measure of their devotion and their courage.

I have, myself, full confidence that if all do their duty, if nothing is neglected, and if the best arrangements are made, as they are being made, we shall prove ourselves once again able to defend our island home, to ride out the storm of war, and to outlive the menace of tyranny, if necessary for years, if necessary alone. At any rate, that is what we are going to try to do. That is the resolve of His Majesty’s Government — every man of them. That is the will of Parliament and the nation. The British Empire and the French Republic, linked together in their cause and in their need, will defend to the death their native soil, aiding each other like good comrades to the utmost of their strength. Even though large tracts of Europe and many old and famous States have fallen or may fall into the grip of the Gestapo and all the odious apparatus of Nazi rule, we shall not flag or fail. We shall go on to the end. We shall fight in France, we shall fight on the seas and oceans, we shall fight with growing confidence and growing strength in the air, we shall defend our island, whatever the cost may be. We shall fight on the beaches, we shall fight on the landing grounds, we shall fight in the fields and in the streets, we shall fight in the hills; we shall never surrender, and even if, which I do not for a moment believe, this island or a large part of it were subjugated and starving, then our Empire beyond the seas, armed and guarded by the British Fleet, would carry on the struggle, until, in God’s good time, the new world, with all its power and might, steps forth to the rescue and the liberation of the old.

Their Finest Hour

June 18, 1940. The Wehrmacht had reached Paris a few days before and Italy had declared war to Britain and France. Mussolini’s commitment to fight the Allies was not that frightening, but clearly, it would have meant that another front, the Mediterranean one, was to be opened. However, Churchill had foreseen it in his first speech. The entire Axis was now fully belligerent.

In London, Churchill and his War Cabinet were getting ready for the oncoming German invasion of the island. Lord Halifax, an influential member of the War Cabinet, had supported the attempt to reach an agreement with Hitler, but the Prime Minister had strongly rejected it. When Churchill stepped in Westminster it was clear that, sooner or later, the Luftwaffe would have flight the British skies.

During the first four years of the last war the Allies experienced nothing but disaster and disappointment. That was our constant fear: one blow after another, terrible losses, frightful dangers. Everything miscarried. And yet at the end of those four years the morale of the Allies was higher than that of the Germans, who had moved from one aggressive triumph to another, and who stood everywhere triumphant invaders of the lands into which they had broken. During that war we repeatedly asked ourselves the question: ‘How are we going to win?’ And no one was able ever to answer it with much precision, until at the end, quite suddenly, quite unexpectedly, our terrible foe collapsed before us, and we were so glutted with victory that in our folly we threw it away.

What General Weygand called the Battle of France is over. I expect that the Battle of Britain is about to begin. Upon this battle depends the survival of Christian civilization. Upon it depends our own British life, and the long continuity of our institutions and our Empire. The whole fury and might of the enemy must very soon be turned on us.

Hitler knows that he will have to break us in this Island or lose the war. If we can stand up to him, all Europe may be free and the life of the world may move forward into broad, sunlit uplands. But if we fail, then the whole world, including the United States, including all that we have known and cared for, will sink into the abyss of a new Dark Age made more sinister, and perhaps more protracted, by the lights of perverted science.

Let us therefore brace ourselves to our duties, and so bear ourselves that if the British Empire and its Commonwealth last for a thousand years, men will still say, ‘This was their finest hour.’

These are very brief passages of Churchill’s wartime speeches, which I strongly suggest you to read. They are crucial to understand that historical period. Hitler was winning over any kind of army all around Europe, and all the other countries were dealing with this. Mussolini, for instance, decided to bring Italy to war just because he believed that the Allies were about to fall. In a situation in which the Wehrmacht looked unstoppable, Churchill didn’t step back. He thought that any sort of agreement with the Führer would have been a defeat for two reasons. On the one hand, it would have been a humiliation for the British, so proud of their island; on the other, it would have made the British government no more than a puppet one.

Another reason why these speeches are hugely important is that they show Churchill’s speaking skills. The words he pronounced were not randomly chosen, as even their sound had a meaning. No doubt, Churchill is one of the most important statesmen of History; not just a British one, but a World one. As a matter of fact, without his perseverance, History would have been pretty different.

History, Politics & Economics – A place for uncomfortable truths.

michelecaimmi98[at]hotmail.com